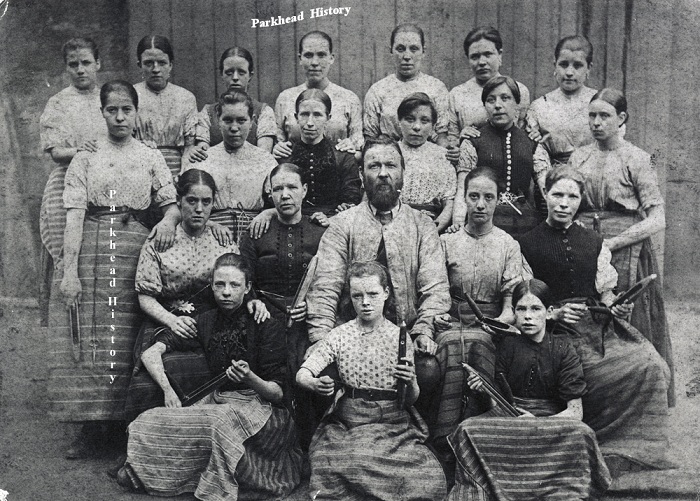

Camlachie Weavers

Below Copyright © Culture & Sports Glasgow (Museums).

Reproduced by kind permission of Culture & Sports Glasgow (Museums).

Camlachie Weavers circa 1892. All are holding shuttles and all are togged out in aprons with scissors and other tools attached to the apron. The gentleman in the photo is probably management.

The Weavers at Camlachie

‘Yesterday (Thursday) a very serious occurrence took place on Camlachie, of which the following are the particulars :-

Mr George Smith, weaver, Camlachie, has a family if six sons and three daughters. He has six looms occupied by himself and five of his sons. He has taken all of his work from Mr Peter Hutchison ever since that gentleman commenced business. He always found that he paid as high prices as were given by any, and he would never seek a better master. He joined the association with the sole view of getting some better regulations adopted respecting the taking of apprentices, and preventing strangers from coming into the trade, so that the hands might be reduced. He would never have joined an association for putting any man out of trade, more particularly Mr Hutchison; and the delegate from Camlachie, when he voted to that effect, went beyond his instructions. On Wednesday Mr Smith went in as usual and brought five webs from Mr Hutchison’s warehouse. When this was known he was called upon in the evening by four of the Committee of that district, who told him they would expel him from the association for taking webs from Mr Hutchison. He said he had done no offence in taking those webs when he was pleased with them, and he did not think that it was anything to do with the Association. They asked him to take back the webs; and if he had got any money upon them, they would make it up. Mr Smith had not received one farthing advance upon the work; but he did not choose to satisfy them at that point, but told them he would not take it back for them or any man, as he never wished Mr Hutchison out of the trade. One of them replied he had a terrible work with Mr Hutchison. He said he had no occasion, for he was always better paid and served with better work than by any manufacturer he had ever tried. They said a weaver who was at the door would give him a sixteen hundred broad lawn, and seek one for himself, if he would leave Mr Hutchison. A man in the street also offered to procure him a shilling a week if he would comply; but all their offers being rejected, the Committee told him he was now expelled from their Association, and went away.

Yesterday morning, between 9 and 10, while Mr Smith was engaged in making new shutters for his windows, his shop was beset by a rabble, who attempted to get into the loom shop, but the door being fastened, they hung about the windows, and cursed him to come out, and they would give him a good thrashing. No answer was given, but those within continued working. They then left the premises but continued to lounge about in groups about the village. About two o’clock they gathered in a field to the north of the village. Some of the most active were noticed engaged in making up an effigy intended to represent Mr Smith, senior. The figure was stuffed with straw, and there was on it clothes exactly resembling those worn by Mr Smith. The white night-cap he wears was not forgotten; and there was the appearance of a web under the figure’s arm, with a white cloth round it; the same as Mr Smith carries with his cloth to the warehouse. Indeed the personification was so complete, that the family say they might have mistaken it for their father, but for the ill-painted face. There was a label on the breast, with the inscription ‘A warning to all traitors for deserting their colours’.

They went by the back of the houses, and came down Whitevale, carrying the effigy shoulder high. There was a number of men and women collected, who advanced with the most horrid yells and shouts, and stopped in front of Mr Smith’s house. They used the most odious names and expressions to the family, and held the effigy close to the window. A fellow with a rope inflicted twenty lashes on it. The crowd then huzzaed and shouted for joy, and went parading the effigy through the village, which was in a state of indescribable confusion. With augmented numbers they reached Parkhead, and stopped at Mr Hall’s, one of Mr Hutchison’s weavers, and who is determined not to drop him; then to Mr Smith’s, beyond Parkhead; then to Mr Dunsmore’s, Westmuir.

At all these houses, and several others who were obnoxious, because they would not leave Mr Hall, the rabble vented their spleen, insulting them and their families in the grossest manner and threatening them. The effigy was flogged before each of their doors.

After the mob had acted in this manner for more than an hour, reinforced by most of the inhabitants of these villages, they returned to Camlachie about four o’clock. In the interval, Mr Smith despatched a messenger to Mr Hutchison’s warehouse, and the foreman went to the police office, and requested the assistance of the civil power. The mob, to the number of 700 or 800, again assembled opposite Mr Smith’s house, held up the effigy to the window, and the women, who were very numerous, and particularly active, and forgetting their natural modesty, used the most disgraceful epithets to the family, and declared they would burn alive. They went to a wooden erection that had been fitted for a flesher’s stand. Her a fellow performed the part of hangman in due form, and after hanging for some time the effigy was taken down. Preparations were in the interim making to burn it, and a quantity of shavings and a shovelful of live coals were taken from an adjoining brick-kiln and laid on the foot pavement opposite Mr Smith’s windows. Here they continued shouting and hallooing, and expressing their determination to burn Mr Smith alive. As they were about to consign the effigy to flames the police came upon them by surprise, and they, quite confounded, dispersed in all directions. The effigy was carried along in the hurry, and was torn to pieces, and a carter who was passing got the remains of the coat thrown in his face. As there were, however, only five of the police, the mob, after the first panic, and observing their small number, began to rally.

Mr Smith’s son pointed out a few fellows to the police, who had been most active in molesting them. The proceeded to town with two prisoners. The mob followed in great numbers and commenced throwing brick-bats and large stones, by which some of the police were severely hurt, and obliged to take shelter on the road side. Captain hardy got into a house and made his escape by a back window. Mr Dobbie, special constable, who had been particularly active in seizing prisoners, is much hurt in different parts of the body by the stones. In the meantime, two officers kept hold of the prisoners, amid a shower of missiles. When they came to the Gallowgate toll, the mob pressed so hard upon them, that Serjeant Thomas was obliged to take refuge in the coal weighing box, No. 5. When they were inclosed, the mob hurled large stones at the windows, which they shattered to pieces, and then broke the lock, and forced open the door, and rescued the prisoner. Mr Sim and the police Serjeant, who were in the box, were exposed to the greatest danger. When the box was broken up, they were pelted with stones, and obliged to run for their lives. The mob followed them, and Mr Sim was struck on the back of the head with a sharp stone and deeply cut, he being bare-headed. He was stunned for the moment, and reeled a little, but was fortunately able to keep his feet, and made his escape with great difficulty.

Some humane individual brought a surgeon, and the wound, which was profusely bleeding, was dressed. An order was then dispatched for every officer in the police office, and all those in the town to turn out. A strong party of them went to Camlachie, and secured five prisoners, and brought them to the police office. A third party of the police again went out and secured two other fellows. Baillie Lang and the Sheriff were also present, and were of the greatest use in restoring order. They examined Mr Smith’s premises, and said thet had never seen a better conducted establishment, and were highly pleased with the industry and regularity which characterised all its members. Mr Smith is a most peaceable well-doing man, and would give no offence to any of his neighbours. His family live very retired, and during the radical rebellion he wholly abstained from it. A grudge, he says, has always been borne him for this. A party of the police remained in the house till eleven o’clock, and on the last alarm measures were taken for an instantaneous communication with the police.’

Glasgow Journal, Wednesday 15th September 1824