CAMLACHIE

THE FORGOTTEN

VILLAGE

BY

PETER MORTIMER

COPYRIGHT © PETER MORTIMER 1998

Tempus Fugit

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

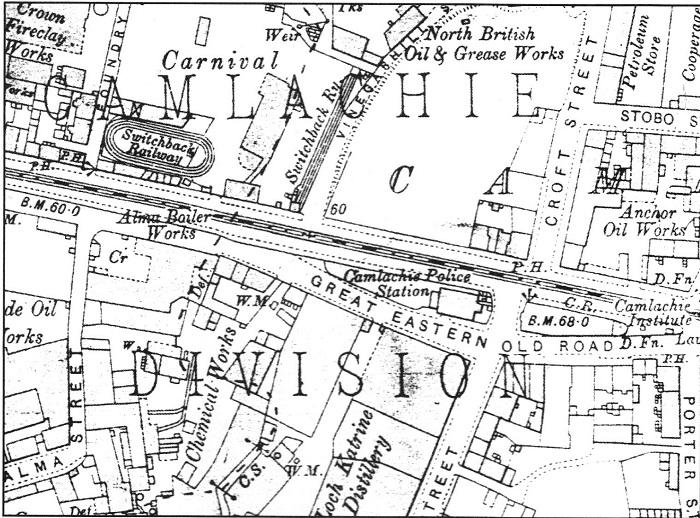

To many Glaswegians the name Camlachie means very little, and to those who have heard of it, it could just as easily be a sort of “Brigadoon”. But, as many eastenders will testify Camlachie exists and has an interesting and eventful history. The name Camlachie means “the muddy bend of the burn” and is derived from the Celtic language. It has been variously spelt over the years, including Camblachie, Cumlachie and Camcachecheyn. The burn referred to in the name is that of Camlachie Burn, which flows through the area. References to Camlachie can be traced back prior to 1300, where it is mentioned in the chartulary of Glasgow, and later around 1590 when “Cumlachie Brig” is referred to in a survey. The lands of Camlachie were divided into two parts, Easter and Wester Camlachie, the boundary being formed by Camlachie Burn.

Wester Camlachie

From around the 1650’s, the lands of Wester Camlachie were owned by William Wilkie of Haghill who sold them on to William Goveane, a writer. Goveane later sold the lands back to another member of the Wilkie family, namely John Wilkie.

The Wilkie family retained ownership of Wester Camlachie until 1669 when John Walkinshaw bought the estate. The Walkinshaws were to play a significant part in the history of Camlachie, and went on to buy the adjacent lands of Barrow-field. John Walkinshaw died in 1689, and ownership of Wester Camlachie and Barrowfield passed on to his son, also named John Walkinshaw. John Walkinshaw the second led an active life and travelled extensively. He in turn passed the lands on to his own son, a third John Walkinshaw.

In 1703 this John Walkinshaw married Catherine Paterson, the sister of Sir Hugh Paterson of Bannockburn, a staunch Jacobite and supporter of the Stuart cause. In 1706 John Walkinshaw helped found Calton village. He was sympathetic to the Jacobite movement and was taken prisoner at Sheriffmuir in 1715 and held captive in Stirling Castle. He was finally pardoned in 1717, but had his lands forfeited, although his wife, Lady Barrowfield managed to retain the estate. In 1720 Camlachie Mansion was built.

In 1722 the estate was managed by William Douglas of Glenbervie as a trustee, to enable Lady Barrowfield to keep the lands. As recompense for carrying out his duties, Douglas was allowed to mine coal at Camlachie, although this proved to be less than successful. The Walkinshaw’s tenancy of Wester Camlachie and Barrowfield came to an end in 1730 when John Orr bought the lands for ten thousand pounds. However, this is not the last we hear of the Walkinshaw name in relation to Camlachie. John Walkinshaw and Catherine Paterson had a daughter named Clementina, who became intimate with “Bonnie Prince Charlie” during his visit to Glasgow in 1745/6. She later bore him a daughter, the Duchess of Albany.

The Orrs, like the Walkinshaws were to have an association with Camlachie spanning three generations. In 1734 John Orr bought Camlachie Mansion, twelve acres of land and the rights to mine coal from Lady Barrowfield for five hundred pounds. In the same year he also acquired the lands of Gateside. In 1744 John Orr died and lands passed on to his son, William Orr. The Orr family resided in Barrowfield House, and in 1753 William Orr let out Camlachie Mansion to a company carrying out woollen manufacturing, but the venture failed.

William Orr died in 1755 and Wester Camlachie and Barrowfield fell to his son, John Orr the second. He, along with his brother Matthew (who inherited Stobcross Estate) formed the Camlachie Coal Company.

Coal operations at Camlachie proved to be very expensive due to frequent flooding, and profits were not forthcoming. In 1770 John Orr the second bought tracts of land known as Crownpoint and Mountainblue had formerly belonged to Humphrey Luke of Easter Dalbeth.

The attempts by the Orr brother at coal mining finally took its toll on family finances, and in 1788 John Orr was forced to sell Wester Camlachie and Barrowfield for sixteen thousand pounds.

The new owners were James Dunlop of Garnkirk and Robert Scott of Meikle Aitkenhead. In 1793 James Dunlop experienced financial problems and was eventually sequestrated, Gilbert Hamilton being appointed as trustee. In 1799 Gilbert Hamilton sold James Dunlop’s interests in Wester Camlachie and Barrowfield to Archibald Graeme, a partner in the Thistle Bank in Glasgow.

In 1805 Archibald Graeme died and his stake in the lands passed on to three of his partners in the Thistle Bank, namely Archibald Colquhoun of Killermont, Henry Ritchie of Busby and James Rowan of Bellahouston. The following year Robert Scott the second inherited his father’s half of the lands. In 1808 William Hozier gained control of Wester Camlachie and Barrowfield, with his son James Hozier succeeding him.

Easter Camlachie

From around 1700 the lands of Easter Camlachie were owned by James Corbet of Tollcross, a wealthy land owner of the area. In 1731 Robert Dreghorn bought Easter Camlachie, having previously worked coal seams there, under a lease granted to him by James Corbet. Around 1749 Allan Dreghorn inherited the lands from his father. In 1750 James Buchanan bought the lands of Easter Camlachie. A separate part of the lands was that of Little Hill, which John Corbet feud to William Boucher of Comely Garden, near Edinburgh in 1751.

In 1756 Corbet sold Little Hill to Patrick Tod of Edinburgh for eighty one pounds. The lands changed hands two years later when Robert McNair bought Little Hill for one hundred pounds. In 1764 McNair built a house on Little Hill and names it “Jeanfield”, after his wife Jean Holms. McNair died in 1779 and his family continued to occupy the house and lands until 1797 when they sold out to John Mennons, printer and editor of the Glasgow Advertiser (later to become the Glasgow Herald) for two thousand four hundred and thirty five pounds. Mennons only had the lands, by now known as Jeanfield, for about a year and sold them in 1798 to John Finlayson, who was married to Robert McNair’s daughter. Finlayson was another man who tried unsuccessfully to mine for coal in the Camlachie district. In 1825 James Harvey, a writer, bought Jeanfield and he also succumbed to the lure of mining for coal, with predictable results, and was later bankrupted.

In 1846 the lands of Jeanfield were purchased by the Eastern Cemetery Joint-Stock Company, to convert the grounds into a necropolis. Also in 1846, Camlachie became part of Glasgow.

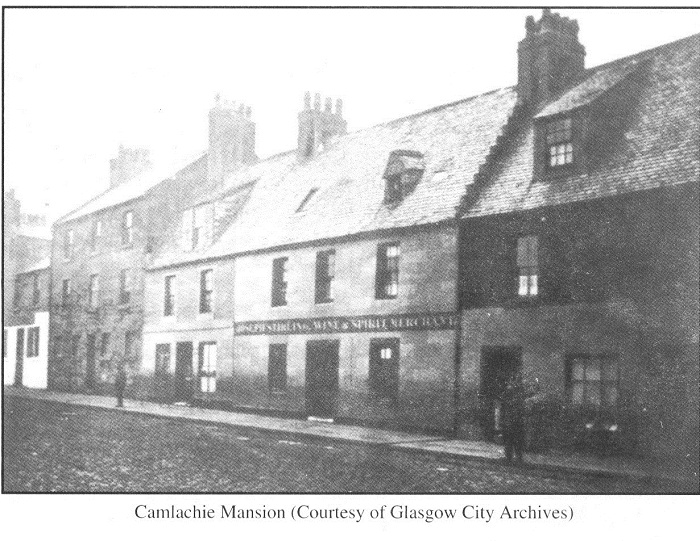

CAMLACHIE MANSION

Built in 1720 by John Walkinshaw and later sold in 1734 to John Orr. It was a two storey structure and stood alone on the main thoroughfare, which was known as Camlachie Lone, and was originally set back from the road with a small flower garden to the front, and larger gardens to the rear. General James Wolfe of Quebec fame visited Camlachie in 1749/50 and resided at the mansion during his stay. In 1753 the mansion was leased as premises for carrying out woollen manufacturing. With the population increasing in Camlachie due to the industrialization of the 1850’s, buildings were added alongside the mansion and it lost its unique identity. It was used as a public house before finally being demolished in 1932. Camlachie Mansion was situated on the north side of Gallowgate, about one hundred and eighty feet east of Millerston Street, in what is now the car park of the Forge Retail Park.

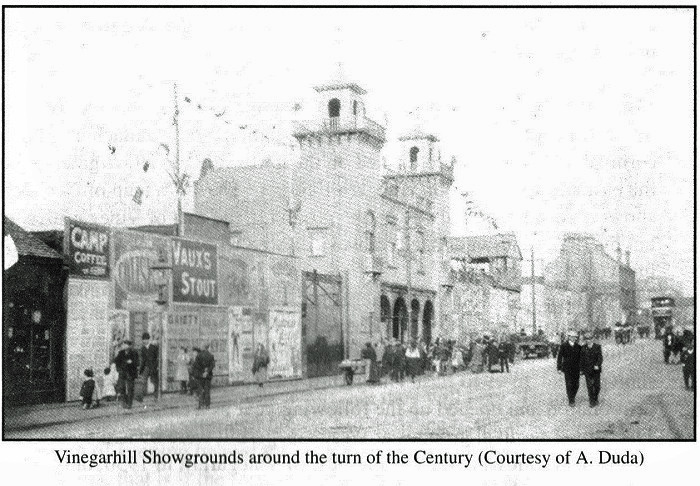

VINEGARHILL

The piece of land known as Vinegarhill plays an important part in the history and development of Camlachie. There may be some debate as to how the area became known as Vinegarhill. It is possibly named after the Battle of Vinegar Hill which took place on the 21st of June 1798 in County Wexford, when General Gerard Lake (1744-1808) routed the Wexford Rebels in what was one of the first clashes between Protestants and Catholics in Ireland. It is more likely however that Vinegarhill derives its name from vinegar works which were sited there when D. King & Co., carried out production of vinegar from around 1837 to 1860. Events elsewhere in Glasgow gave Vinegarhill its best known identity. In the early 1870’s the city fathers decided that the carnival and circuses that appeared during the Glasgow Fair opposite the High Court in Glasgow Green would have to be relocated, and moved them to Crownpoint and Vinegarhill.

Crownpoint did not survive for long for the showpeople, and they had to move from Rochester Street when the Corporation decided to build a tram depot there in 1893.

Vinegarhill became the prime site in Glasgow for the annual carnival, and the showpeople were to have a long association with Camlachie. The carnival or “shows” were located on the north side of Gallowgate, on both the east and west sides of Vinegarhill Street. The 1896 map of Camlachie shows a switchback railway on the ground to the east of Vinegarhill Street, but by 1912 two switchback railways existed within the walled carnival to the west of Vinegarhill.

The postal address for East Vinegarhill was 918 Gallowgate, and an examination of the 1928-30 voters roll reveals that there were 190 adults eligible to vote, giving some idea of the importance of the site to the showpeople. In 1930 East Vinegarhill was acquired by Glasgow Corporation and opened up the following year as a children’s playground.

The walled carnival grounds at West Vinegarhill were owned by the Green family, and following the closure of East Vinegarhill in 1930, only selected families made the move to West Vinegarhill.

The attractions and events at Vinegarhill have been many and variable, and it is interesting to look at some contemporary newspaper articles over the years;

The Detective – 16th July 1885

“Among The Shows at Vinegar Hill”

“The “shows” with their yards of flapping canvas, still brave the breeze. Doubtless our social progress has condemned them to an obscure grave, but they die hard. The showman is not easily killed, his canvas always a fascinating influence over the juvenile portion of the community, and the pictures that adorn the exterior of the booths are sufficiently tempting to induce the youths to deliver up his penny at the door. The degenerate condition into which the “Fair”, as represented at Vinegar Hill has gradually fallen bespeaks at no distant date total collapse. The good old days that made Glasgow Fair famous are gone, and in their place we have a collection of starved hares and canaries, smooth faced giants, mysterious looking females, colossal alligators, and diminutive men and women.

Leaving historic Trongate, and skirting along Gallowgate, dodging in turn train-cars and old women with apple stalls who implore me to invest, I reach the Fair ground. What a noise! the yelling, howling, swearing, laughing, thieving, and devilry. What a combination of brass bands, steam whistles and organs! Here every human contrivance is put into operation in order to draw the hard-earned copper from the pockets of the artizan. Everything under the sun, from “Birds of Paradise” to “Tamed Rats”, all are crowded together in this small square for the benefit of holiday makers. Trumpet speaking men proclaim the excellence of their particular show, about which “there is no deception”. Zulus dressed in their native costume execute war dances on the platform and invite visitors to step inside Tragedians, arrayed in all their glories of tin helmets and spangled jackets, with wooden swords, loudly assert that they will play “Hamlet in five long acts”. Fairies, in satin and muslin bid defiance to the time honoured custom of keeping behind the curtain, and strut on the outside stage as alligators, that is if the representations on the canvas are correct, and a sudden impulse to view the aforesaid snakes seizes me. But my desire to enter is nipped in the bud, a sheet of paper the writing on which announces the show is “full”, so I have to pass on.

Every show is not doing such a roaring trade as the “snakes”, and seduced by the oratory of a cockney I elbow my way through a motley crowd of acrobats, clowns, equestrians, and ponies, to the door where an old lady collars my penny, after which performance, I am allowed to enter the “Grand Circus”. The audience is not large and mostly composed of youths who are tumbling head over heels, crawling below the seats, and indulging in other acrobatic tricks with a view to qualifying themselves for real circus work in after life. As the last shout is given “Begin”, and the performers take up their place in the ring. A piebald pony is introduced, and a youth who attempts to wipe paint off with his bonnet is very promptly cuffed by the clown. The old circus tricks are repeated, and in ten minutes we are again in the open air. Allured by the notes of an execrably played fiddle, I enter a palace of delight called a “penny gaff’. But the place is abominably dirty, and the odour of the company and of the lurgan twist they are smoking is powerful, so very powerful that it frightens me and I bolt.

A sparring booth is the next place worth of notice. Professors of the “noble h’art” are haranguing the crowd, and invite all and sundry to step in and have a “go”. I am not at all inclined to pay twopence for the privilege of having my nose double its ordinary size, so again I pass on. “A reg’lar beauty”, shouts a bleary-eyed, dissipated looking fellow, “weights twenty-six stone”. I gazed at the enormous size of the woman depicted on the canvas, and then at the very small proportions of the caravan, until I am lost in wonder as to whether the woman holds the house, or the house the woman. It is no use disputing the “beauty” of the woman as tastes differ, and I leave the proprietor, though he doesn’t look like one, endeavouring to entice open-mouthed urchins inside the tent. During the next few minutes I am in the midst of the “hares”, “snakes”, “wonder workers”, and “jugglers”. Insinuating owners of ghost shows try to wheedle me within their web, but I am obdurate. Sometimes a pretty, occasionally an ugly, face makes a fierce dart at me from a shooting saloon, and endeavours to thrust a gun into my hands; now a lazy Italian, with his ice-cream, seizes me by the arm and whispers his price into my ear. But I am not to be wheedled and passing rapidly over the smaller fry I reach a booth clean and tidy in its outward appearance, where “Alonzo the Brave” is the chief attraction. I enter the temple of drama, passing in my ascent, villains, robbers, and heroes. There is a large audience composed of every conceivable grade, from the swell with his eye-glass and spats, down to the dirty faced urchin who wipes his nose with the cuff of his ragged jacket. Here is a youth indulging in his first dissipation of summer drinks; while there is another one who is cramming cakes of gingerbread down what appears to be a bottomless pit. And here is a factory girl, who has come to have a good “pen’orth” of the drama, while there is the gamin all eyes and ears for the commencement. “The band will play the last “toon on the h’outside”, cries the first robber, “and then we go h’inside to begin”. The musicians strike up “God save the Queen” and the actors make their way through the audience and pass through the stage door. The band is seated, there are two or three preliminary flourishes on their part, and then the curtain is rung up. I do not wait the consummation of the drama and amid the murmurs from the pit I see the door. The rain is falling heavily and the crowds are gradually melting. Therefore, and as I have had enough of the shows for one season, let us jump into this tramcar bound westward, and seek the cosy circle around the fireside”.

The Glaswegian – 15th July 1886

“There is the usual display of tinsel and canvas, high flies and discordant music, at Vinegar Hill this year. There are the usual crowds of pleasure -seeking lads and lassies, and to all appearance this year’s show is much the same as on previous occasions. One new feature, however, fails to be noticed, and it is the securing of one of the tents for religious services on Sunday. This is as it should be. These showmen are for the most part strangers in our midst and are unacquainted with our manners. It is only our duty to see that some form of worship is provided for them, and it is to be hoped this system will not be reserved to Glasgow or to the present holiday season”.

Glasgow Eastern Standard – 25th July 1936

“When Vinegar Hill Was At its Zenith”

“During the past quarter of a century the Gallowgate east of East John Street (Millerston Street) has not changed much from what we knew it in the “seventies and eighties”, except for the frontage of the old Vinegar Hill Showground. Many old houses are still standing, but the old showground is open to the street without gate or stile in the old days. In the sixties, I think, the fair was still held in what is now called Jocelyn Square, a better title than Jail Square of old time. The booths and stalls then had to find “fresh fields and pastures new”. This they found at Crownpoint and Vinegar Hill. With the building of tramway stables in David Street the ground at Crownpoint was lost and the entire fair housed at Vinegar Hill. This was a piece of waste land on which there had at one time been a foundry – possibly David Napier’s. Down one side flowed the Camlachie Burn, a wretched looking little stream. In winter time it was a sea of mud, and in the summer a Sahara of dust. The atmosphere was odorous with the smell of oil, tars, currier’s grease, resin, and other things being prepared or manufactured.

The Fair ground was arranged in some sort of plan. The big shows formed a half circle at the back of the ground. There were two entrances of a kind at the east and west ends, with an inside circle between these of smaller booths and stalls for the sale of sweets, hot peas, lemonade, toys, etc., on either side of a make shift street. Inside this circle also were most of the merry go rounds, hobby horses and velocipedes. The big shows were pretty good and well worth the small charge of admission. Why, I once saw the entire play of “The Silver King” in twenty minutes done in the best style, a la Wilson Barrett!

The Ghost Show was excruciatingly funny. This was Clarke’s adaptation of Pepper’s Ghost by means of plate-glass. It was the show that Barrie mentions in “Auld Licht Idyllis”. Trowhead went to the exhibition, but from his seat he could see behind the scenes, and saw more than he intended. He laughed when the rest laughed, but he never saw where the fun came in! Then there were the shooting ranges, much affected by the young men of the period, where you might have the pleasure of having your rifle loaded by your mother’s “stair-girl”. Needless to say, the guns were muzzle loaders. Then there were the booths showing feats of jugglery, acrobacy, pugilism and wrestling. The “Brummagem Chicken” would wrestle the world. Standing aloof from the rest of the Fair was a permanent erection -that is, it was of wood, not canvas. This was “The Adelphi Theatre”, which was run by Mrs David Prince Miller, widow of a former famous Glasgow actor-manager.

Swallow’ Circus, also a wooden erection, stood at the opposite end of the ground from the Adelphi. Here was good equestrian entertainment from a penny to fourpence, with the clown’s very latest seventeenth century jokes thrown in!

Then there was the inevitable fat woman, the swings, the “Waterloo Fly” – an instrument of torture now forgotten, and the children’s delight, the hobby horses and velocipedes. It is in this class that the most revolutionary changes have taken place. Many of the merry go rounds were still worked by boy or man power, and the wheezy old hand organ was not yet displaced by the piano organ or the brazen blarer.

For the operations of the merry go rounds boys who volunteered to turn the crank would get a free ride. The velocipedes were an imitation of the old iron “bone-shaker”, and one had the pleasure of working a real pedal. It is said that once, on the occasion of the owner having retired to General Wolff’s House to get rid of the dust in his throat, the riders on the wheels took control of the contraption and nearly killed the poor boy at the crank! It was good entertainment, and it need not cost you a ha’penny. Many thought that they got more fun outside than in. The painting of the fat wife was more gruesome than the person herself – in any case boys were not admitted. You saw the girl mesmerized, lying on the point of a stick fastened on the outside platform, you also saw, on the same, all the actors in “Sweeny Todd, the Barber”, dressed for their parts. People have different ways of amusing themselves today – but whether or not they are happier is a moot point”.

When the carnival left Vinegarhill and moved on to Glasgow Green, the showpeople continued to house their caravans at Vinegarhill, and it was finally closed in the mid 1980’s. It now forms part of the Forge Retail Park.

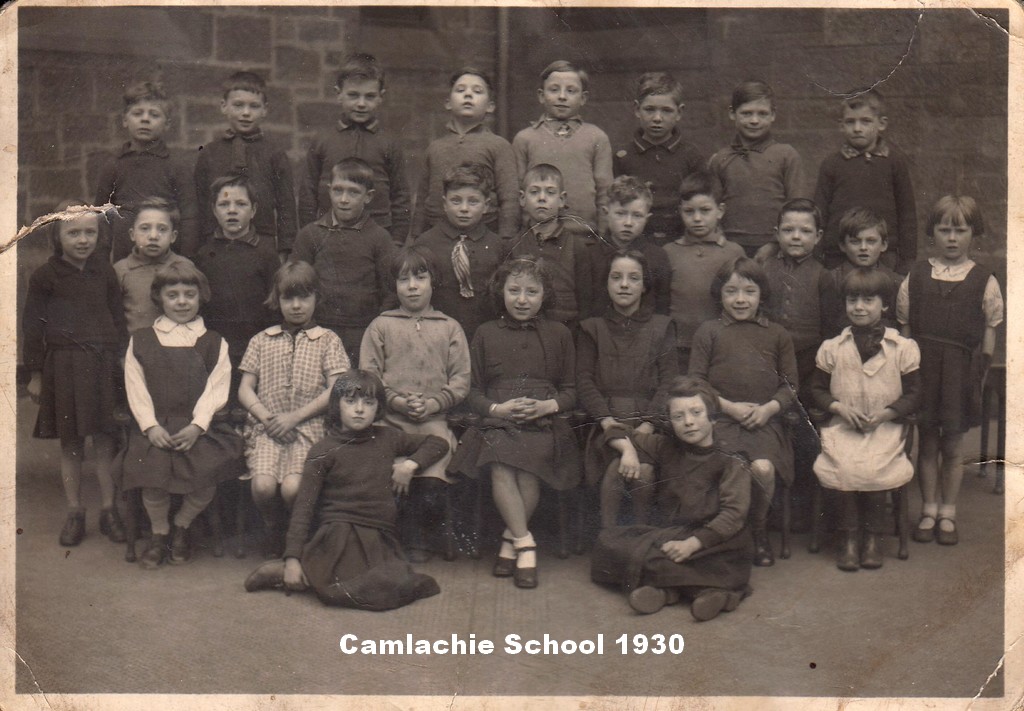

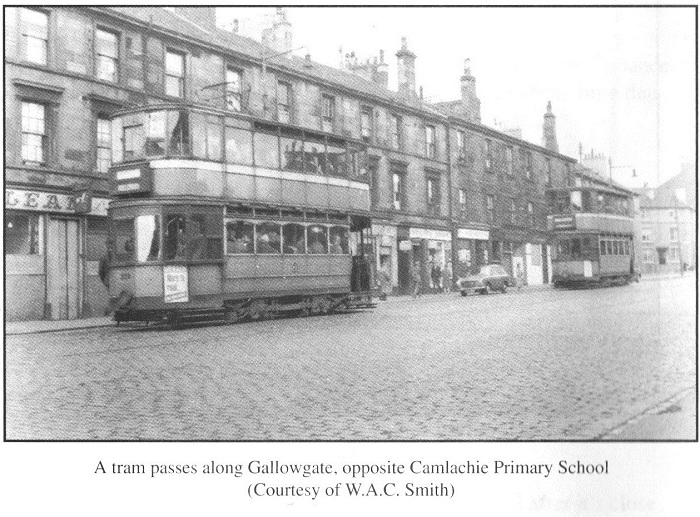

CAMLACHIE PRIMARY SCHOOL

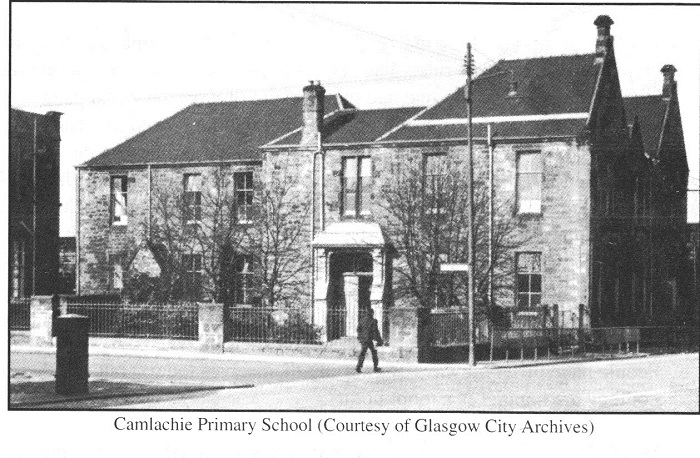

As rapid industrialization hit Glasgow from the 1850’s onwards, so grew the population. Camlachie went from being a small weaving and mining village, to an industrial district. Schooling for the old village is thought to have taken place in a small building in Yate Street, but this became inadequate. And so, to provide a proper establishment to educate the children of the district a new school was built at the corner of Holywell Street and Gallowgate.

Camlachie Primary School was opened on the 1st of May 1876, and the first headmaster was a Mr. Galbraith, who only stayed to the following month, when the school broke up for the summer holidays. He left to join Parkhead Public School.

In August 1876 Andrew Hoy took over as headmaster and remained in post until March 1883. Andrew Hoy faced, more than a hundred years ago, similar problems to his counterparts of modern times, as an extract from the school log dated 13th October 1876 reveals: “Punished two boys for marking one of the wall maps with lead pencil”.

The school inspector’s report of 8th December 1876 also noted:

“The school is getting into good working order and is being filled up with very poor neglected children”.

School attendance has long been a thorny issue, and even in the 1870’s headmasters had to produce statistics for the Education Department. Examination of the Monthly Return dated 24th December 1876 makes interesting reading;

| Boys | Girls | Infants | Total | ||

| 1) |

Ave. No. of Roll |

343 | 321 | 122 | 786 |

| 2) |

Ave. No. in All |

259 | 227 | 76 | 562 |

|

3) |

Highest Attendance |

280 |

234 |

74 |

588 |

|

4) |

Complete Attendance |

104 |

87 |

23 |

214 |

|

5) |

Absent all Month |

23 |

21 |

21 |

65 |

|

6) |

Enrolled |

5 |

6 |

3 |

14 |

|

7) |

Struck Off |

53 |

22 |

8 |

83 |

|

8) |

Ave. Att. From 1st Nov |

299 |

237 |

81 |

617 |

James Mackenzie took over from Andrew Hoy in March 1883 and was headmaster for a further three years. He was succeeded by Robert Black who was the former head master of Kent Road School. Black stayed at the school for four years until February 1890, when he left to join the staff of Gallon Public School.

The next headmaster was Edmund Foggie, who had previously been in charge at David Street Primary School. Following Foggie’s departure in February 1890, Robert Davies joined Camlachie Primary School from St. Matthews Primary and remained until the summer of 1904, when he left for Parkhead Public School. James Martin took over and left after a four year stint to move to Centre Street School on the south side.

Robert Butters was appointed headmaster in September 1908 being followed in September 1912 by William Armstrong, who stayed until December 1915, when he left to take up a position in Garbraid Street School.

The school then had a succession of headmasters, many of whom only completed a three or four year term of office:

| James Lindsay |

1916-1921 |

| William MacFarlane |

1921-1924 |

| H. Goldie |

1924-1927 |

| Wm. S. Paterson |

1927-1930 |

| John Campbell |

1930-1933 |

| Thos. H. Neilson |

1933-1935 |

| Robert McKinlay |

1935-1938 |

| Murdo Macrae |

1938-1943 |

| Elizabeth Henry |

1943-1951 |

| Alfred Greenwood |

1951-1957 |

Helen Muir took over from Alfred Greenwood and stayed in post until the latter days of Camlachie Primary School.

Being headmaster of Camlachie Primary School over the years has not just been about teaching. The head of staff has had to adopt other roles, such as social convenor and clerk of works, as extracts from the school Letter Book reveal;

To: Director of Education 26th Sept. 1933

Dear Sir,

The staff of the school proposes holding a Jumble Sale in the Drill Hall here on Saturday 28th October 1933 from 2.30 to 6.30 p.m. in aid of the School Fund and I herewith make formal application for the use of the Hall on that date and during those hours.

The School Fund is used to secure equipment for schools organisations, to purchase prizes and Merit Badges, and generally, to promote the happiness and welfare of our pupils in this poor locality.

I Remain

Yours faithfully

Thomas H. Neilson.

To: The Director of Education 129 Bath Street C2 8th April 1943

Dear Sir,

On November 20th 1942 I made a request for an electric gong to ring simultaneously in both buildings, and on 28th December a flimsy was received here saying “Repair and alter position of bell”. As there is only an old battery bell in a state of complete disrepair I should like to have my requisition of 20th Nov. reconsidered.

The reason for the requisition is that there is no recognized way at present whereby I can be summoned from any classroom other than by an exhaustive search, I, too, have no means of summoning the janitor when his services are required. As the outside bell cannot be ringing, teachers have difficulty in hearing a whistle for assembly and dismissal, and on occasions bad timekeeping results. It would also be of great advantage for fire drill and air raid practice. For all these reasons I trust that the work of supplying and installing such a bell as I have requested may be duly sanctioned.

I am

Yours faithfully

Elizabeth Henry

Camlachie Primary School closed in June 1974 and was later demolished. The site is now used as a football pitch.

INDUSTRY

For a small district, Camlachie has played host to a large variety of industries over the years, in fact weaving, coal mining, distilling, engineering, barrel and casket making, brick and pottery manufacture, carting, chemical production, grease and gut production amongst others, have all been carried out in Camlachie.

One of the earliest commercial activities in Camlachie was weaving, and as a small satellite village of Glasgow, it had an active weaving community. During a period of particular industrial unrest, a Camlachie weaver named George Smith refused to support his peers in a strike in April 1820. He further aggravated the situation when he agreed to carry out weaving work at a lesser price than the tariff recommended by the local weaving committee. George Smith very quickly became an unpopular person, and matters reached a peak, when an unruly mob numbering over 700 descended on his weaving shop in Camlachie. They went on to burn an effigy of him with a label pinned on stating “A warning to all traitors for deserting their colours”.

As we read earlier coal mining at Camlachie was never too successful, and many people associated with it fell victim to the huge financial burden it imposed.

Due to the availability of clay, pottery making in and around Glasgow was commonplace, and Camlachie in the nineteenth century was recognised in this craft.

Mountblue Pottery was established by William Lyon, who had been a sugar planter in Jamaica, and reputedly named his pottery after the Blue Mountains of that Caribbean island. The pottery was originally located in the vicinity of what is now Overton Street in the Barrowfield housing scheme. William Lyon had started his career working with his father in the firm of W & G Lyon, coppersmiths and tinplate workers who carried out their business at Candleriggs until 1829. William then went on to form his own company, William Lyon around 1830 at 124 Buchanan Street. Around 1842 William Lyon went into partnership with John Lawson to form the company Lyon, Lawson & Co., located at Mountblue.

They advertised their business as being “millwrights, engineers and brick and tile makers”.

The venture lasted until 1861 when there appears to have been a change of direction. William Lyon went on to form J & W Lyon & Co., who specialised in brick, tile and earthenware manufacturing, whilst John Lawson went it alone as a millwright and engineer. Shortly after the split, William Lyon relocated the Mountblue Pottery about five hundred yards east, in what is now Stamford Street. John Lawson was later acquired by John McPherson & Co. in 1874.

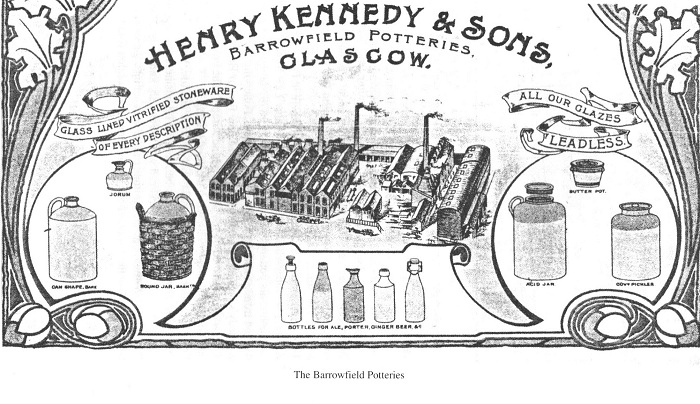

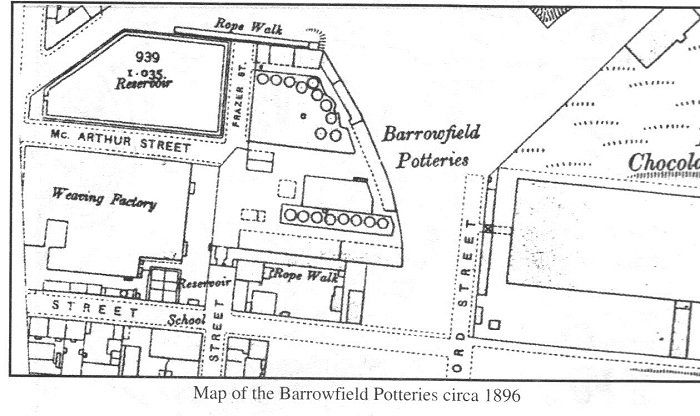

The largest pottery in Camlachie was the Barrowfield Potteries of Henry Kennedy & Sons, which was sited at what is now Law Street. Kennedy established his pottery at Barrowfield around 1870, though prior to this he worked from an address at Mauldslie Terrace. Following his death in 1890, Kennedy’s business was dissolved and the new firm of Henry Kennedy & Sons was established by his sons John and Joseph. The business continued operating till around 1930, when it ceased trading.

Probably influenced by the availability of brick and tile, William Steven, one of Glasgow’s early tenement builders, set up business at Vinegarhill Street. Silverdale Street in Parkhead was previously known as Steven Parade, and William Steven’s initials can be seen set into the stonework of the tenement on the corner of Silverdale Street and London Road.

Engineering began in Camlachie around 1800 when Duncan McArthur opened his Greenhead Foundry, which was located close to Lyon’s original Mountblue Pottery.

Around 1810 McArthur was joined in his venture by David Napier, who was to be one of the early pioneers of shipbuilding on the Clyde. In 1815 David Napier, in partnership with his father John Napier, opened Camlachie Foundry near to Camlachie Burn at Vinegarhill. It was here that in 1816, David Napier built his first marine engine for the vessel the “Marion”. By 1819 McArthur’s business had failed and was dissolved, and in 1823 David Napier moved his works to the new Lancefield Foundry, nearer to the River Clyde. The Camlachie Foundry was then leased to David’s cousin, Robert Napier, who in conjunction with David Elder continued to manufacture marine engines at Camlachie. David Elder’s son John went on to form the shipbuilders Randolph, Elder & Co., who became John Elder & Co. in 1870.

In 1885 they became Fairfield Shipbuilding & Engineering Coy., and were best remembered for the marvelous liners they built for Samuel Cunard. In 1965 Fairfields went into receivership but later emerged as Fairfields (Glasgow) Ltd., becoming Upper Clyde Shipbuilders three years later. In 1972 they formed along with other yards the consortium known as Govan Shipbuilders Ltd. They are now part of the Norwegian group Kvaerner, who took control in 1988.

Distilling began in Camlachie in 1834 when Coventry & Belsland established Camlachie Distillery beside the Camlachie Burn, using the plentiful supply of water. Later that year they formed the Camlachie Distillery Company and the following year re-named the distillery as Whitevale Distillery.

In 1835 the firm was sequestrated and two years later ownership fell to James Guild Jnr., whose father owned the Calton Distillery. By 1847 Camlachie Distillery had once again changed hands, when Hector Henderson took control. He already owned a distillery in Islay and in 1849 began a rebuilding programme of the works. Around 1850 he formed the company of Henderson, Lamont & Co., to see it sequestrated two years later.

In 1855 Matthew and Archibald Bulloch of Bulloch & Co., were the new owners of Camlachie Distillery, and in 1859 they became Bulloch, Lade & Co. In 1866 they re-named the distillery, now to be known as the Loch Katrine Distillery. Around the same time the distillery was further extended with a mains supply of water replacing Camlachie Burn, which by now had become unsuitable. During this period the distillery was producing a fine lowland malt whisky.

In 1896 Bulloch, Lade became a limited company, and the turn of the new century saw further development of the site in 1902 and 1903. In 1920 Bulloch, Lade & Co. Ltd. were in financial trouble and were taken over by a consortium headed Distillers Co. Ltd. This saw the end of distilling at Camlachie and in September 1920 it was converted into a bonded warehouse and makings. Facilities at Camlachie were of a high standard with a cooperage and engineering workshop located within the works. Also based at the distillery was the area fire officer and his department, and he received a commendation for his work in the salvaging operation following the Cheapside Street fire in March 1960. Contained within the distiller)’ was Burnpoint House, a villa for the use of the distillery manager, but later served as an office. A garden and greenhouses, where tomatoes and grapes were grown, were also a prominent feature of the distillery, and during the Second World War Polish soldiers were billeted for a time in the warehouses. In the post war years Camlachie continued to be used as a bonded warehouse, and finally closed at the end of March 1985, with the existing stocks being transferred to Menstrie and Port Dundas. The distillery was demolished some time later.

Camlachie had long been the centre of the carting industry in the east end of Glasgow. Consequently, cartage contractors, horse dealers, blacksmiths and hay merchants all located in the district. In former times carting contractors congregated at 5.30 in the morning at the island site at Camlachie Institute looking for hires. Work was to be had moving coal from the pits at Parkhead and Shettleston down to ships on the Clyde, or transporting other cargo from the railway goods yards at Camlachie, Parkhead or Haghill. The carters built their own mission hall at 56 Holywell Street.

THE STREETS

Alma Street

An “L” shaped street that runs from Camlachie Street to 370 Crownpoint Road. It takes it’s name from the Battle of Alma, which took place on the 20th of September 1854, during the Crimean War. The Alma Boiler Works which stood in the street at the junction with Great Eastern Old Road (Camlachie Street) were established by James Neilson around 1854.

Arch Street

Ran from 1023 Gallowgate to Biggar Street. First appears in the ordnance survey map of 1896. No longer exists.

Biggar Place

Cul-de-sac off 5 1 Biggar Street and was originally known as Broad Street.

No longer exists.

Biggar Street

Cul-de-sac off 1009 Gallowgate and previously formed part of Broad Street. Site of the Camlachie Glass Bottle Works which were established around 1865 by Stevenson & Little, and were later owned by Robert Paul & Co. Now forms part of the by-pass around the Forge Shopping Centre.

Brewers Open

Ran off 128 Camlachie Street and provided access into the Camlachie Distillery, as shown on the 1 860 map of the area. By 1896 it is no longer named and is merely an entrance to the distillery.

Camlachie Street

Runs from 792 Gallowgate to Stamford Street and was originally known as Great Eastern Old Road. At No. 100 stood an acid works, founded in 1813 by Turnbull & Ramsay, later to become Turnbull. Stuart & Co., who operated through until 1965. The works were demolished two years later. At No. 130 stood the Camlachie Distillery, premises of Distillers Co. Ltd.

Coalhill Street

Ran from 1051 Gallowgate to Dunrobin Street. Appears on the ordnance survey map of 1860 and possibly derives it’s name from a coal bing that may have been in the area serving a local mine.

Croft Street

Cul-de-sac off 989 Gallowgate, no longer exists. First appears on the map of 1896 and provides access to a manure works and also the Crownpoint Glass Bottle Works. Site of the Emmanuel Church. By 1912 both the manure works and the church have been demolished.

Dunrobin Street

Runs off Society Street and was originally known as East Union Street. Site of the Camlachie Pottery, which was owned by Watt & Co., and traded in the 1860’s.

Foundry Open

Cul-de-sac off 823 Gallowgate, no longer exists. Named after its close proximity to Camlachie Foundry. In 1860 it provided access to the Camlachie Foundry. On the west side near to Gallowgate stood two closes and further up was the rear of the Whitevale Chemical Works.

Fraser Street

Cul-de-sac off 1171 Gallowgate and originally formed a path to Longpark

Cottage and was previously known as Carntyne Place. No longer exists.

Frazer Street

Runs from 937 London Road to Law Street. At No. 27 stood Barrowfield Primary School, built around 1876 and now demolished. At No. 50 stood the premises of Daniel Clark, ropemakers.

Gallowgate

The main thoroughfare through Camlachie and was originally known as Great Eastern Road, a name it kept until 1925 when it became part of an extended Gallowgate. At No. 867 stood the garage premises of J.M. Wilson, motor engineers. At No. 1004 stood the Camlachie Institute which was opened on the 1st May 1890. At No. 876 stood Camlachie Police Station, built around 1876, and demolished in 1977. At Nos. 993 to 1015 stood the Anchor Oil Works, established around 1883 by Marks & Johnston, oil refiners and merchants. They continued to operate from the site until 1933 when they ceased trading. The location was later occupied in 1939 by the Croft Bodybuilding and Engineering Col. Ltd., who redeveloped the site and remained there until it’s closure.

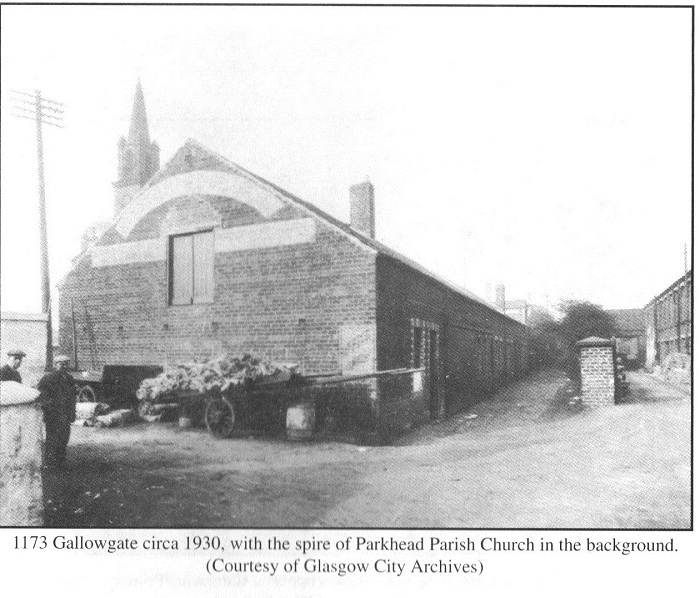

At no. 1141 stood the premises of McCrae & Drew Ltd., hair and bedding manufacturers. Originally the firm of R & J McCrae. they merged in 1928 with the Paisley company of M. Drew & Sons Ltd. The office building still survives, and is currently the premises of Richard Irvin & Co. At No. 1159 stood Parkhead Parish Church. At No. 1179 stands the premises of Hunter & Clark Ltd., established in 1900 when Thomas F. Hunter and William Clark formed the business. Hunter was the monumental sculptor and had previously been a partner in the firm of Arnott & Hunter, who operated from premises opposite the necropolis gates. At Nos. 1264 to 1270 stands the Eastern Necropolis, which was laid out as a cemetery in 1847 on the site of the lands of Janefield. The cemetery lodge dates from around 1865. Throughout the length of Gallowgate in Camlachie, stood many shops, pubs and other establishments catering for the needs of the community.

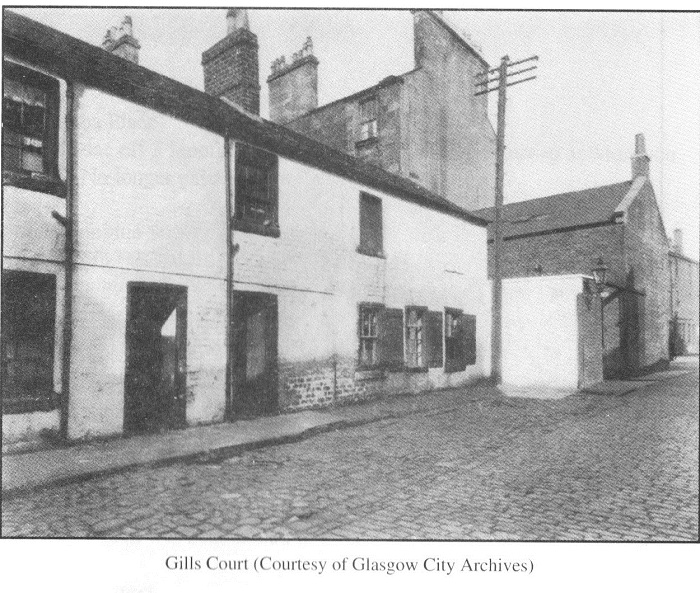

Gill’s Court

Cul-de-sac off 1052 Gallowgate, and previously known as Guild’s Court. May have been named after James Guild, who is listed as an occupant of Camlachie in the Directory of Gentlemen’s Seats and Villages in Scotland. Alex Hodge, carting contractor had stables sited here, and also to hand was Andrew Brodie, blacksmith. Gill’s Court no longer exists as such, but now forms the goods entrance to the Cardowan Creameries, who own the Parkhead Factory in nearby Holywell Street.

Holywell Street

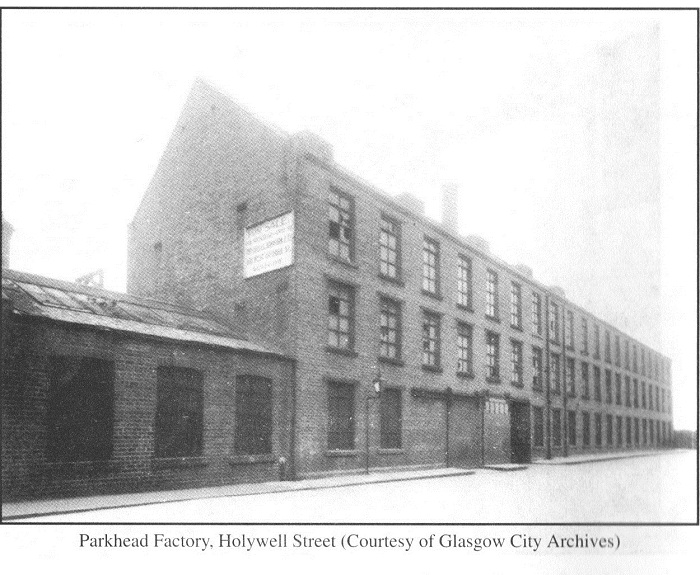

Runs from 1046 Gallowgate to Janefield Street and was previously known as East Hope Street. At Nos. 49 to 51 stands the Parkhead Factory, built in 1866 for Clark & Struthers, gingham manufacturers. Later became the premises of Cardowan Creameries, who still operate at the site.

Humber Street

Ran off Society Street and was previously known as East Hill Street. No longer exists.

Janefield Street

Runs from 180 Stamford Street to Springfield Road, though originally ran through to Gallowgate where the upper portion was known as Porter Street, until around 1928. Derives its name from Robert McNair’s lands of Jeanfield, which he named after his wife Jean Holms. At No. 80 stood the Mountblue Cooperage, premises of Thomas Stevenson, and later became known as Camlachie Cooperage. Site of prefabs which were demolished in 1963 to make way for new housing built the following year. After falling into disrepair, this development too was demolished, in 1997.

Manitoba Place

Cul-de-sac off 3 Janefield Street and was previously known as Morrison Place.

No longer exists.

Mountainblue Street

Runs from Fielden Street to Yate Street and is named after the Mountblue Pottery which was in the vicinity. The pottery took it’s name from the Blue Mountains of Jamaica. At No. 64 stood the Barrowfield Park, home of Bridgeton Waverley Football Club. The park was built around 1927 and remained in use until around 1939 when it was demolished to make way for the Barrowfield housing scheme.

Society Street

Originally ran from 1063 Gallowgate to Humber Street, though it is now much shorter. May have taken its name from the Camlachie Old Friendly Society which was established in 1772.

Stamford Street

Runs from 995 London Road to 1020 Gallowgate, with the upper portion being known as Porter Street (see Janefield Street). At No. 50 Porter Street stood the Nelson Recreation Ground which was built around 1923, and was owned by a local horse dealer William Nelson, who had premises at nearby Nos. 15 to 31 Porter Street, the sportsground was used as a flapping track and occasional boxing venue, and became known as the Olympic Sports Stadium in 1935, before being demolished a couple of years later. At No. 100 stood a chocolate factory, built in 1899 from the Sweetmeat Automatic Delivery Co., who specialised in the manufacture of chocolate bars and confectionery for use in early vending machines. The site was later taken over by Reeves & Co., another chocolate manufacturer before becoming the premises of Sunblest Bakeries Ltd., and later demolished in the early 1990’s.

Stobo Street

Ran from Croft Street to Biggar Place. No longer exists.

Van Street

Cul-de-sac off 1253 Gallowgate, no longer exists. At No. 15 stood a van and lorry works, built in 1904 for J.H. Kelly. Later became the premises of Wm. Beardmore & Co.

Vinegarhill Street

Cul-de-sac off 867 Gallowgate, no longer exists. Named after vinegar works which were in the vicinity. At No. 49 stood the North British Oil & Grease Works, built in 1875 for Joseph Jack, oil distiller and grease manufacturer. At No. 61 stood a gut works, built in 1907 for John Noonan, gut merchants.

Yate Street

Runs from 976 Gallowgate to Law Street. At No. 55 stands a confectionery works, premises of Edward McKenzie, manufacturing confectioners. Now the premises of A.L. Ellsworth. At No. 85 stood a works, premises of Vulcanite Ltd., felt manufacturers, and later used by Brander Cullen Engineering, now demolished.

————————————————————————————————–

Yate Street Jail At The Gallowgate

Camlachie for Barrels

Industry fast Dying

Goods go All Over the World

The East Ender who has a casual walk in some of the side streets of Camlachie will discover a veritable forest of barrels. In Janefield Street there are thousands of them, stacked up to perilous heights, occupying every available inch of space.

A Standard representative elicited some interesting information. Camlachie it appears is the main centre of the cooperage industry in Glasgow, and indeed for a great area in the West of Scotland.

Barrels come from America to Camlachie, and thence go to India, China, Belgium, Iceland, Australia, and indeed all over the world.

There is a historic reason why Camlachie has been associated so intimately with the coopering industry.

Formerly the greatest users of barrels were oil, paint and tallow manufacturers. Those Industries for many years centred in Camlachie, and so cooperages also came to be near to their best customers.

Wooden barrels are not generally made in Camlachie, as the price of a new barrel is now prohibitive.

The barrels are brought from America and sold second hand to the Camlachie cooperages, where they are made like new, air tight and watertight. Camlachie coopers are at the departure of every boat carrying cargo contained in barrels, just in case a barrel may need a last minute repair done on the spot.

Many of the original barrels from America contain butter and lard. They are cleaned in Camlachie, and then sent to Denmark and Belgium, filled with the self same commodities, and re-exported to Britain.

Coopers have a long and arduous apprenticeship

, but the increasing use of machinery has resulted in the depressing but irrefutable fact that the industry is a dying one.

Steel drums are now replacing barrels, while oil is now pumped into huge tanks of lorries and then direct into tanks on board ship.

Forty years ago there were nine large cooperages in Camlachie, now there are only a third of that number worthy of the name.

Taken from the Eastern Standard 1934

Photo of the staff at Barrowfield Pottery

Sorry , camlachie

Was there a gypsy site or camp in camels hie in the 1950’s ?

Hi Bob,

Have a look at the Vinegarhill page on the site. This will answer your question.

I find the website to be very interesting as I track my genealogy back to Scotland. In the census for 1881, 1891, and 1901 my great grandfather is listed a living at 389 New Road, Registration District: Camlachie, Civil Parish: Glasgow Barony. I have searched many maps of Glasgow but cannot find New Road on any of them. Did it exist in the Camlachie to which this site is devoted? I realize that streets come and go, but even historical maps show no trace of it. It appears in later postal directories (1890’s) but with only a few numbered houses on it. Any help you can give me would be appreciated.

Hi Keith

New Road ran from Parkhead Cross to Carntyne Road and joined up with what was then Duke Street. New Road was renamed Duke Street shortly after 1900 and the existing Duke Street took in what was New Road. I’ve sent you more info and map by email.

Its so sad now to go up to the retail park and think that a whole wee village communitiy is gone forever.. and hardly anyone will remember it ever existed in a few years…My auntie lived in Arch st and won either Spot the Ball or Littlewoods, wasnt a great amount for back then in the 50s £250 I think it was, but it was big enough to put on the billboard outside the newsagent up there on the Gallowgate. My other auntie moved from Broad st in Bridgeton when it was being demolished to Dunrobin st in Camlachie.. I hated her house as the living room had no view , it looked out on to the side of the railway bridge and got no light in…

sorry I repeated myself in that post as Id already told about my aunt in Dunrobin st . put it down to age… haha.. I was in Janefield earlier this year to have a look at my granny and uncles grave up the back at the wee wall where there was prefabs , now long gone.. Im not sure if that wall has sunk or Ive grown a wee bit.. but it seems a lot lower than I remembered it all those years ago.. as I went every sunday with ma auntie from the early 50s to the sixties when for some reason my auntie stopped going … and I dont think shes ever been back.. maybe I should go with her one day , as shes getting on now and might want to visit.. Sadly, for my granny having such a big family, they never thought to put together and get her a marker of some sort, it didnt have to be elaborate , just something with her and my uncle who died youngs name… its so sad that no one will ever know whos there .. or care for that matter…

Hi I lived at 1035 gallowgate in the 1960s my dad ownwed the fruit shop ( nicks grocers ) he worked in it with my mum freda she was english and he was greek , and I was born in the good old gallowgate !!!!!!! My wee auntie katie and uncle stevie cannon stayed 2 closes up from us , does anyone remember them ? We left in1970 to go to easterhouse , I went to camlachie school for 2 yrs , I will always remember the gallowgate it has great childhood memories !!!!! GREAT WEBSITE ENJOYED LOOKING AT THE OLD PHOTOS helen hendry

Wee TV Repair Shop near Parkhead Cross Hi Everyone, Great to read some of the stories of the east end.I spent my early years playing in the \”Hairy Work\” ie the chemical works in Society Street.My grandad lived at 1209 Gallowgate and when I used to visit him my dad would go to a wee TV repair shop in Gallowgate(abt No 1249) opposite Janefield Cmty just before Van Street .The shop was piled with old tellies and my dad would get a spare valve for our TV from this wee man.We are talking about the late 1950\’ and early 1960\’s.Can anyone tell me the name of the TV man.I\’ve tried on the Glasgow Forum but this site seems more likely to come up with an answer(I hope) Keep the stories coming. J

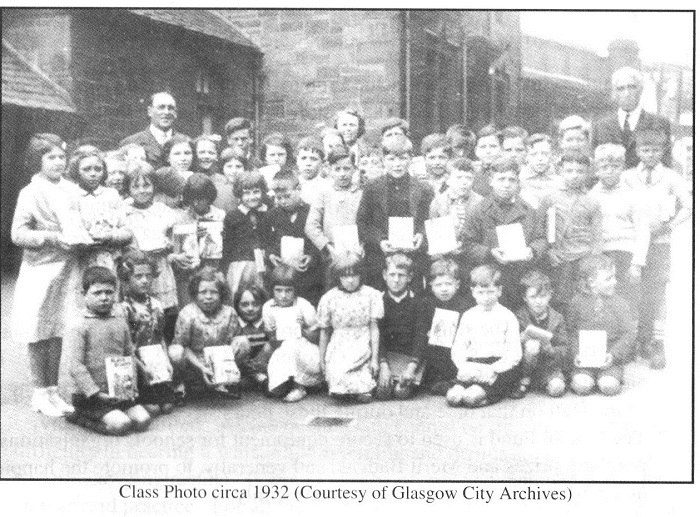

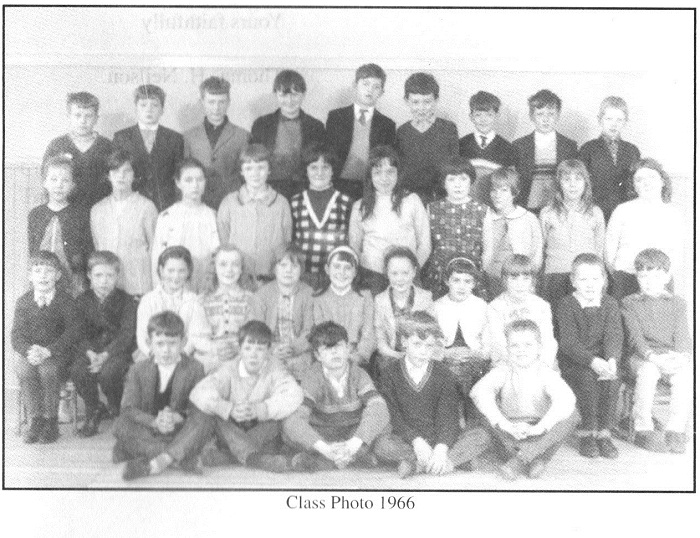

Hi Ken, good to hear from you, I am seated on the second front row at the extreme left, beside Jim Softley.

I am the young man back row, centre, wearing jacket, shirt, tie and mustard jersey.leaning to the left. I am 11 years old . I still have this school photo, loved my time their. The headmistress, Mrs Muir ? gave me extra reading tuition, which enabled me to Riverside Senior Secondary. Many thanks for a wonderful read.

hi I got the website from tam m,cann I think it is brilliant not enough of this type of site I cannot get enough of them

Hi Bob. My apologies – will re-send the photograph to you asap. I have now found my grandfather Robert Roy in this photograph. He worked for Alex Hodge as a carter in the early 1900s, was married to Agnes Riddell, daughter of Daniel Riddell. Robert’s brother William Roy married Agnes’ sister Mary Riddell.

My father, also Robert Roy, learned to play the bagpipes at Gill’s Court. As you know he later became the Piper Of Tobruk.

If anyone knew him in his younger days in Glasgow, I would love to hear from them.

Thank you very much for your help. Have sent old photo of Alex Hodge workers to Parkhead History group and hope someone may recognise an ancestor of mine – a Roy or Riddell.

Alice.

Very interesting information. Do you know where Alex Hodge (carter contractor) was located in around 1900?

Hi Alice,

Alex Hodge Carting Contractor had premises at 106 Great Eastern Road and lived at Overwood Villa in Tollcross between 1894 and 1901 (approx). From 1902 his premises were at 190 Great Eastern Road and in 1933-34 he was at 1060 Gallowgate. As Alex Hodge died in 1923 then I believe that it was his son Alex who may have been at 1060 Gallowgate.

Prior to 1894 he was at 4 Great Eastern Road.

Hi Alice,

A. Hodge were at 190 Great Eastern Road in 1900, which was actually known as Guild’s Court, and later corrupted to Gill’s Court. The street still exists in a slightly different form, as it now forms the enrarnce off Gallowgate to Cardowan Creameries whose premises are in the adjacent Holywell Street.

I hope this helps.

I remember Lachies shop near or under the Croft bridge, cheery man who I think sold fruit. then there was a chipshop round the corner going down to Barrowfield, dont remember the name of it now.. just at the arches of the bridge..

Had two aunties that lived in Camlachie, one above the Grange pub and one in Dunrobin st her house backed on to the railway bridge..her back windows looked into nothing but a wall, so she kept her curtains closed most of the time… I remember the big house across the Gallowgate, set into the grounds of the graveyard. at one time my auntie with the big family was supposed to move into it but never came to anything and she moved to Commonhead.