Belvidere Hospital

In 1870 relapsing fever invaded the city, and the accommodation of the Parliamentary Road Hospital – the first hospital erected by the Corporation, opened on 25th April 1865, containing 136 beds, and extended in 1869 to 250 beds – was speedily exhausted.

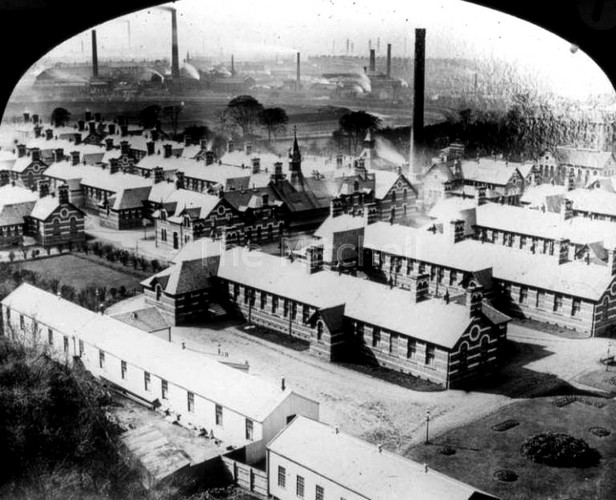

After the usual trouble in obtaining a site, the estate of Belvidere, extending to about thirty two acres, was purchased by the Corporation for £17,000, converted into a ground annual of £680. The smallpox hospital was the first permanent erection. Operations were begun in November 1874 and the hospital was completed and formally opened on 5th December 1877. It contains 150 beds in ten wards, arranged in five isolated pavilions. The total cost, exclusive of site, was £30,235. The fever hospital has grown up from year to year by substitution, addition, and re-construction into its present form. It began with temporary wooden pavilions, and large sums were spent in maintaining these for some years. The total amount of money expended on hospital and grounds is about £90,000. The wards are distributed in pairs, in thirteen isolated pavilions, containing 390 beds.

The estate of Belvidere near the north banks of the Clyde about two and a half miles east of the city was acquired and a fever hospital opened there in 1829. By 1832 it had 220 beds and in the 1870’s a separate smallpox hospital was added with 150 beds—a clear indication of the continuing presence of this dreaded disease. Belvidere treated a wide range of infectious diseases, from typhus to smallpox and diphtheria, but much of its work was treating the then common childhood diseases of scarlet fever, measles and whooping cough. In 1887 the main hospital had been increased to 390 beds. Belvidere was described at that time as ‘the largest fever hospital outside of London’. When the housing estates of Newbank and Lilybank were built, the people wanted Belvidere demolished as they thought an infectious and contagious disease hospital should not be situated within close proximity of houses.

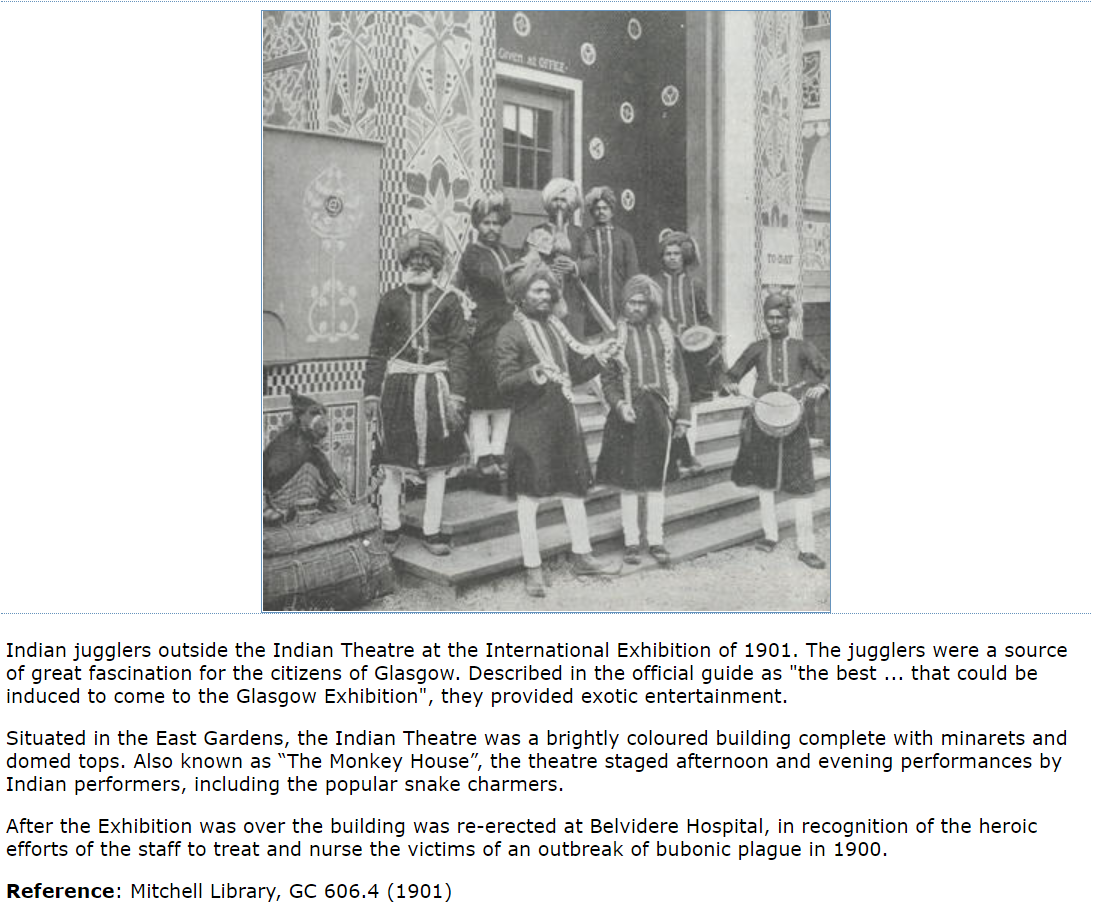

Reproduced with kind permission of Mitchell Library

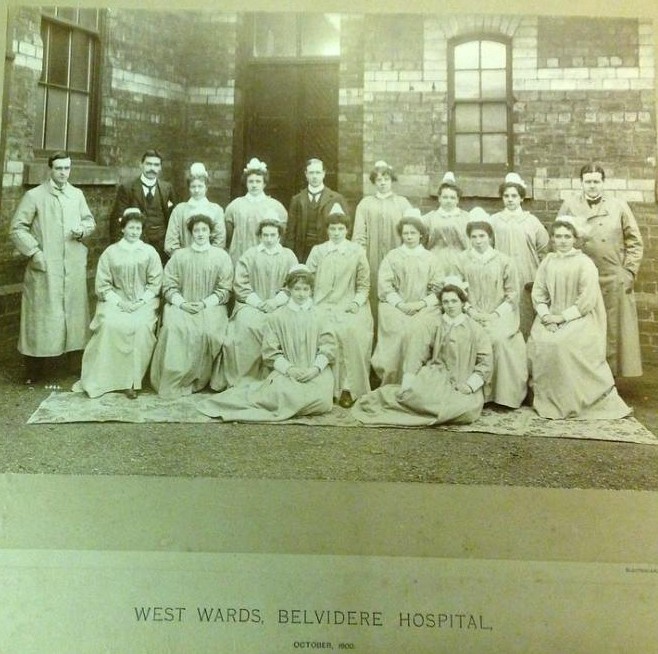

Nurses from Belvidere 1900

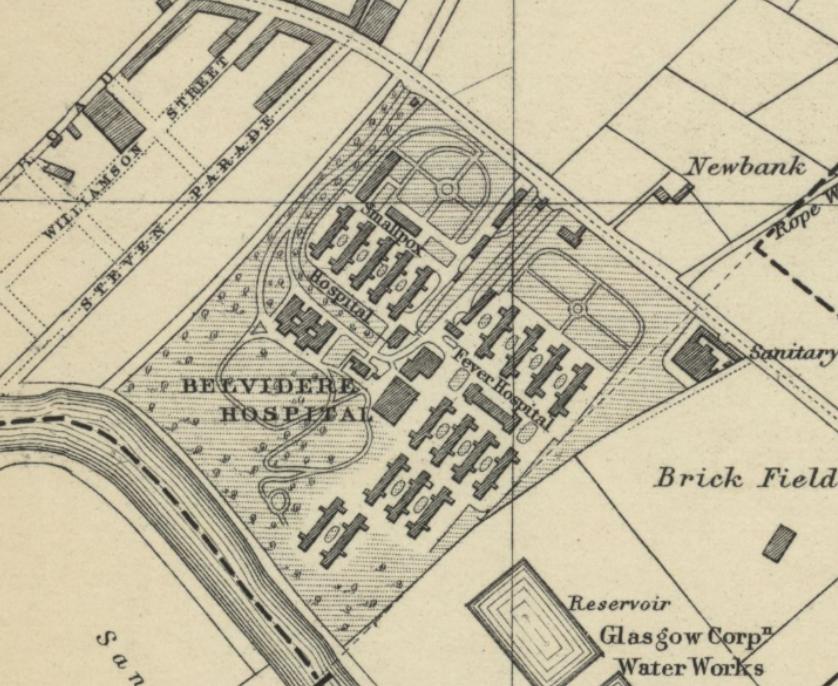

Map of the grounds of Belvidere 1900s

Belvidere Offices just before demolition photo courtesy of Dazza

Belvidere Offices just before demolition photo courtesy of Dazza

BELVIDERE HOSPITAL, LONDON ROAD (demolished) John Carrick, the Glasgow City Architect, was employed by the Town Council from 1870 at the Belvidere Hospital. In 1874 he designed the first of the single-storey, polychrome brick ward pavilions. This unusual treatment for hospital buildings in Scotland gave them a utilitarian air reminiscent of Glasgow’s industrial buildings. The simple polychrome of thin, horizontal bands of white amongst the red bricks created a streaky bacon effect. This treatment was abandoned for the administration block, which also contained the nurses home, recreation hall and senior staff residences. It was a large, austere stone block.

When Glasgow Town Council opened the Parliamentary Road Fever Hospital in 1865, more beds had still been required and in the Autumn of 1870, Belvidere House and its 33 acre estate were purchased to provide a site for the new fever hospital. The first wooden pavilion was occupied on 19 December the same year, and by March 1871 there was space for 250 beds (although, rather alarmingly, 366 patients were in residence).

In the following year it was decided to build a smallpox hospital at Belvidere. Great lengths were taken to ensure that the most up-to-date features were incorporated in the design and many other hospitals were visited to this end, including the Herbert Hospital in London ‘reputed to be the finest specimen of a pavilion hospital in existence’. By 1882 the first five brick pavilions had been built and Belvidere house was being used as the residence of the Medical Superintendent. In the same year the Medical Officer for Health in Glasgow, J. B. Russell, produced his ‘Memorandum on the Hospital Accommodation for Infectious Diseases in Glasgow’, which resulted in Carrick’s expansion of the site. Russell’s memorandum itemised the requirements for a large infectious diseases hospital and considered various details of its construction. He drew attention to many new developments, including the surface treatment of the main walls at Tenon’s hospital in Paris.

The extended hospital was officially opened on 4 March 1887 with 390 beds. In the ‘Report of the Official Inspection by the Lord Provost, Magistrates and Council’ the different buildings and their functions were described. The inspection began with the administration block.

A handsome three-storey stone structure, built on the site of the old mansion house of Belvidere. The chief features of the original building have been reproduced and there have been added at each side substantial wings. The central portion contains the board room and accommodation for Doctors and Matron, while in the additions there are dormitories and sitting rooms for eighty-two nurses.

In 1929 a house was provided for the Medical Superintendent and a new observation ward was opened in 1930. After the inception of the National Health Service various additions were made and changes in function introduced. Two important developments at Blevidere were the opening of the first Cobalt Therapy Unit in Scotland in February 1961 and in March 1973, the opening of the second Neutron Therapy Unit in Britain.

The hospital closed in 1999. After years of neglect the derelict buildings were mostly demolished in 2006 – all except the administration block and nurses’ home. [Sources: Strathclyde Regional Archives: Account of Proceedings at Inspection of New Hospital for Infectious Diseases erected at Belvidere, 1877: J. B. Russell, ‘Memorandum on the Hospital Accommodation for Infectious Diseases in Glasgow’, 1882: ‘Report of proceedings at Official Inspection…’, 1887 Corporation of City of Glasgow, Municipal Glasgow, Glasgow, 1914.]

Belvidere Colliery

Belvidere Colliery

Belvidere Colliery – On Tuesday an accident occurred at Belvidere colliery to the eastward of this city, which had at first a very alarming aspect.

The colliery has not been working for about three weeks, having been undergoing repair, and during that time the hard coal, thirty inches thick, filled with water. When the water is drawn away, the roof of the pit becomes soft, and the stones fall from it, sometimes to the extent of seven carts in one mass, and obstruct the proper current of free air. About eight o’clock on Tuesday morning, some of the colliers descended the pit, which is32 fathoms deep, for the purpose of opening the trap-doors to clear the air-course, and remove the stones that had fallen from the roof.

The workmen had proceeded from the pit bottom, on their way to the work-rooms, about 60 or 70 yards, when they encountered fire damp. Several of them fell from inhaling the impure air, and on returning to the bottom of the pit, three of the number were missing. By the exertions of the oversman, one of the men was immediately brought up in life. In making the attempt to recover the two others, three more were overpowered. One of those that first fell, Henry Reid, belonging to Parkhead, was brought up at 11 o’clock. Every exertion was made by Dr Craig to recover him for two hours, by trying to inflate the lungs and putting him into a warm bath, but life proved extinct. He was found lying on his back, which is a bad position for inhaling the gas, and though he was a strong man, his chest was weak. He was a sober industrious man, and has left a family.

It was distressing to observe the anxiety of those who had friends working in the pit, and who were arriving from all quarters. The workmen belonging to the pit, with two or three exceptions, refused to go down, although Mr Houldsworth offered each man a reward of five guineas. A number of stranger colliers, and two weavers, volunteered their services to bring up five that were still below. At three o’clock, three of the men were brought up in an exhausted state; but by the most unremitting exertions they all recovered. Some of those who so gallantly volunteered their services, were themselves repeatedly overcome by the foul air, and were drawn up in an insensible state. They, however, no sooner recovered, than they again went down on their humane errand. At nine o’clock at night another man was brought up, who also recovered.

Three of those who recovered were six hours in the pit. They describe their sensations to have been like a person becoming very drowsy, and then losing muscular action, repeatedly dropping down and rising up, imagining there was nothing wrong with them, till they had lost all recollection. They state that it would be a very easy mode of death, being without the least pain. The only remaining collier in the pit, a young man of the name of Sharpe, could not be found that night, the searchers carrying no light, as they were afraid of an explosion, and only groping their way in the dark. He was one of those who went down to save the deceased, and was given up for lost.

Yesterday morning at 10 o’clock to the great astonishment of every person, he was discovered breathing, after being 26 hours in the pit, and the usual remedies being applied, he is now in a fair way of recovery. He also states that he fell into a lethargic powerless state, and gradually lost all recollection. He was found lying stretched with his face to the pavement, which is considered as having been the means of saving him, as whatever pure air exists in such a crisis is next the ground. The neighbourhood was crowded all day, and the most exaggerated reports were in circulation as to the extent of the disaster [The Times 24 January 1826]

Belvidere Drivers 1900s

Belvidere Drivers 1900s