DENNISTOUN

PAST AND PRESENT

By

JAMES BAIRD

FOREWORD

By Ex-Treasurer James Barrie, J. P.

THE HISTORY OF DENNISTOUN, Past and present, is well worthy of being put on record. The proximity of the suburb to the centre of the city, and its ready access by car, has made it one of the most populous areas among the many that are growing up.

The History and Romance of the district are fittingly set forth by the author, Mr James Baird, and I have, great pleasure in recommending it as a book worthy of being read by the residents in the district.

The area of ground covered by the term “Dennistoun” has undergone many changes from that originally intended by its former owners. It would seem from the original feuing plans that villas and terrace houses were intended to be erected, but the increase in population and the demand for tenement houses altered the whole complexion of the district.

Without being too boastful, the inhabitants of Dennistoun can truly say that no other district in the city is so well laid off nor better equipped in every respect, than their own. The Churches and Schools in the district are well-known landmarks, and their ministers and teachers have had fame beyond the confines of their field of labours.

The reader of the History will come to the conclusion that within the last century men of outstanding note and ability lived in the district, and have left their mark in the history of our city; and, while many of the notable families have now no longer a connection in the district, the present population maintain the traditions of those who have gone before, and the suburbs continues to grow in extent and importance and makes one feel that they live within the confines of an area full of historical interest, attached as we are as Citizens of the Second City in the Empire.

JAMES BARRIE.

Dennistoun, September, 1922.

DENNISTOUN

Past and Present

DENNISTOUN, now an important suburb of Glasgow, sprang into existence as such during the last half of the nineteenth century. The lands of Dennistoun (Mr A. H. Millar tells us in “Bygone Glasgow”) were known three centuries ago as ” The Craig’s ” (Celtic, “rock”), and’ were divided at a later date into Easter Craigs and Wester Craigs, containing the estates of Craigpark and Whitehill, while Golfhill occupied a large portion of Wester Craigs. The former division belonged to the Merchants’ House, and Craigpark was disposed of about the middle of last century and passed through the hands of various proprietors.

In 1793 Craigpark was purchased by John Gordon of Whitehill and added to the adjoining estate. Five years afterwards these lands were acquired by James McKenzie, merchant, Glasgow, who built a mansion about 1798 and gave the name of Craigpark to the whole estate, which extended from Ark Lame to Cumbernauld Road and from Duke Street to Townmill Road. There were three approaches through the grounds to the mansion—from Ark Lane, from Duke Street (on the lime of the present Craigpark Street), and from Cumbernauld Road, the first of these being the main entrance.

Mr McKenzie was a prominent citizen, and rose to the position of Lord Provost of Glasgow in 1806. In 1820 he opened the whinstone quarry at Craigpark, from which a large portion of the road metal for the macadamised streets of Glasgow was obtained. He died at Craigpark House on 13th June, 1838, in his 78th year-. His wife survived until 1859, hut nine years before her death the estate was sold to Alexander Dennistoun, by whom the new suburb was projected.

Golfhill, like Easter Craigs, had been acquired by the Merchants House in 1650, and was sold in 1756 to John Anderson, merchant, who transferred it to his brother Jonathan Anderson, also a wealthy Glasgow merchant. After the death of the latter, his trustees sold Golfhill to James Dennistoun of the Glasgow Bank, and a magistrate in the city, and by him the mansion of Golfhill was built.

On referring to one of the earliest maps of Glasgow-that prepared by James Barry in 1793 – one finds that east of the Cathedral very little is shown. There appear a few straggling houses east of the Drygate, but besides ” The Craigs,” referred to, there are only other two names in the neighbourhood where Dennistoun now stands—first, The Town Mill, and second, Blochern (now Blochairn).

The Town Mill was situated on the banks of the Molindinar Burn, the famous Glasgow stream associated with Saint Kentigern and others—on the Townmill Road, north of Alexandra Parade. It was a Bishop Cameron in the old days who, as a Lord of the Barony, granted the citizens the privilege of erecting a mill here. In those days it was reckoned a valuable concession to have a mill all to themselves. The only stipulation by Bishop Cameron was that two pounds of wax candles had to be supplied yearly for lighting up the shrine of Saint Kentigern in the “Lower Churen of the Cathedral. It was on the 4th February, 1446, the burgesses and community agreed to this.

The mansion-house of Blochairn stood near where the present Steel Works are. It is recorded that when Dr Thomas Chalmers, the great Disruption leader, was minister first of the Tron Church and afterwards of St. John’s, and lived in Charlotte Street, he spent many summers at Blochairn House, which was at that time a beautiful place of residence. The proprietor was then a Mr Parker, whose wife was an aunt of the late Principal Rainy of Edinburgh (whose father was then a Professor in the Old College in High Street). Carlyle met Chalmers here.

The Firpark (now the Necropolis Hill, belonging to the Merchants House) was termed in the twelfth century “The Crag.” This hill was originally a seat of Druid worship. When used as such there would, be a circle of stones here round which, according to the widespread custom of our Celtic forefathers, they danced at sunrise and made invocations to the Deity, the visible symbol of which was the sun. If tradition be credited that the hill was originally a centre of Druidism, then we see a possible explanation for the site of St. Kentigern’s cell (which ultimately became the site of the Cathedral) that it was erected on the opposite side of the ravine of the Molindinar as a Christian centre to counteract the influence of Druid paganism.

We will commence our pilgrimage of Dennistoun from the site of Golfhill House, home of the Dennistoun family, which stood between Circus Drive and Alexandra Parade (behind Golfhill Public School). It was demolished in August, 1922.

One of the Dennistoun family (who became Mrs Sellar, wife of Professor Sellar, of St. Andrews University) has written a very interesting book, “Recollections and Impressions,” and she gives many glimpses of Golfhill as it appeared in her early years and also gives some information in regard to the founding of Dennistoun as a suburb as well as pen portraits of the founder and other members of the family. I now intend to give a number of quotations from her book:—

Mr James Dennistoun (the founder of Dennistoun) was the grandfather of Mrs Sellar, and she remembers one day spent at Golfhill with him, when he showed her over the garden and greenhouses. “He was a remarkable man in his way, full of vigour, energy and common sense.” He made a large fortune, and was most liberal and generous to all who needed a helping hand. More than thirty years after this, when she met Thomas Carlyle at Professor Masson’s house, he said to her:—“I used to hear much about your grandfather. He was a ‘ captain of industry,’ and did more good and helped more people to rise to the eminence they attained, than will ever be known.” He founded the “Glasgow Bank,” which was incorporated in the Union Bank of Scotland.” Mr Peter McKenzie says that “he had more to do with the prosperity of the City of Glasgow than any man that ever lived, He put down his name for the first £100 for the Gas Company’s shares when gas was first being introduced into the city for experimental purposes. Many of his friends’ chided him that it would be a dead loss, but he paid down the money without a murmur, and it gladdened his heart when he received this note:—Mr D. will please call or send to this office for his dividend of 10 per cent.’ ”

Mr. McKenzie further says:—”Worthy old gentleman, we can never think of him without affection and profound respect. He was so kind and affectionate in his manner and so liberal, leaving a fortune of £300,000 to his family, who have hearts worthy of their sire in the use, and disposal of it.”

When Mr Dennistoun retired from the banking business, in 1829, the principal inhabitants of the city, to show their respect for his high character, gave a public banquet in his honour in the Royal Exchange Buildings, when Dr Chalmers, the minister of St. John’s Church, said:—” Give me something like the wholesome liberality so nobly exemplified by Mr Dennistoun and ere long righteousness shall run down our sweets like a mighty river.”

Dr Chalmers and Edward Irving—who was assistant to Dr Chalmers for three years and thereafter was a popular preacher in London, was deposed for heresy and came back to Glasgow only to die at midnight one gloomy December Sabbath in 1834, in hi9 42nd year, in Parson Street, Townhead— were frequently entertained at Golfhill House by Mr Dennistoun. For his exertions fin supporting the Reform Bill of 1832 Mr Dennistoun, it is said, had the distinction of refusing a baronetcy from Earl Grey.

Mr James Dennistoun was born in 1752, and in 1786 married Miss Mary Finlay of the Moss, Stirlingshire (hence the origin of Finlay Drive and Moss Street). She was very handsome, with ‘beautiful blue eyes and black hair; but, says Mrs Sellar, beyond being gentle and amiable, I do not remember hearing of her personal qualities except of her strong vein of laziness, which often made her work a hole in her finger to save her the trouble of picking up a thimble.”

Mr James Dennistoun had a large family, the eldest of whom was Alexander. His eldest daughter was Elizabeth, who was the mother of Mrs Cross, whose son married “George Eliot” (Miss Marian Evans), the novelist. Mr James Dennistoun, after the death of his wife, married again and had three daughters. One of these married a Mr McDowall, of Garthland, Wigtonshiire (hence Garthland Drive). A sister of Mr McDowall married Mr William Ingleby (hence Ingleby Drive).

After the grandfather’s death, Mrs Sellar’s father and his family went to live at Golfhill, which of course was very different then from whet it is now in surroundings, &c, the house being there and beautifully situated. “Then,” says Mrs Sellar, ” the Molindinar Burn still ran clear at the foot of The Knowes, which was a fairy playground for the children with its broom and gorse and caves and sandhills, all becoming the scenes of Sir Walter Scott’s poems or romances, as one after the other took possession of their minds and timed to make them living realities. The high park —now a slough of despond—was edged by the Wood Walk, and, with two enchanting round plantations’ tenanted by knights and ladies, stretched up green and cheerful to where the steeple of the Cathedral and the tall monument to John Knox looked upon it. Mrs Sellar’s mother was an American lady—Eleanor Jane Thomson, of New Providence — Mr Alexander Dennistoun having married her in 1823. She was-married in a riding habit, which seemed to be the fashion in these days, although the unsuitability of it—wanting any connection with the natural complement, the-horse—never seems to have struck the people of that time. Mrs Dennistoun was slim, with beautiful eyes. One said of her: “She was the most radiant creature she had ever seen.” She seemed to sing rather than talk, to run rather than walk, and came like a; sunbeam into the lives of her much older sisters-in-law. She was the idol of her nieces and the pride of her silent, grave husband. Mrs Sellar’s memory of her, alas! was of a time when sorrow had nearly if not quite broken her heart, and when her eyes were fuller of tears than smiles. Par the finest of her children was James, her first-born; and not only was he singularly handsome, but his mental gifts were quite as remarkable, and he was the very pride of his father and mother’s hearts. Only one vivid remembrance had Mrs Sellar of him, and that when their Uncle John Dennistoun was elected Liberal M.P. for Glasgow in 1837 (which be represented for the first ten years of Queen Victoria’s reign).

Then James and his two brothers, on their ponies—two cream-coloured and one brown—rode, attended by a groom, through Glasgow with bine silk banners, bearing appropriate mottoes in gold letters. James, when he was 13, caught scarlet fever. It spread to the other two boys and to the mother. She and James were the most seriously ill and he died when she was ill and too delirious to be told. He was in the grave several days before she knew that the light of her eyes had been taken from her and all her bright hopes for him quenched. It was a cruel blow, and it was feared it would kill her. It did not do that—possibly she wished it had—but it killed the spring of life in her, and Mrs Sellar says she does not (think she ever smiled again. Other sorrows were to follow. Her youngest girl died a year after, and in three months a dear little dark-eyed boy; in 1847 another blow came with the death, at Gareloch, of a loveable, unselfish boy of 15 from consumption. The mother nursed him night and day, and the consequence was that her poor over strained body sickened of the same complaint. She was taken to Golfhill, and there, after lingering for two or three months, she joined those whom ” she had loved and lost- awhile,” and found the rest and peace her heart and soul had craved for and could never find in this world of death and partings.

Mr Alexander Dennistoun, the father, although he had never had a regular business training, had a genius for finance, and it used to he said of him that whatever he touched turned to gold. He was very fond of pictures, and had a good collection. They were a perpetual joy to him, and he lay Still and silent on his sofa gazing at them. He was too silent a man to have much to say to children, but he liked their company, and they felt his silence to be friendly and cheerful and never knew a moment’s restraint in his presence. He liked during his visits to Gareloch to take the same drive with the children each day, and one day one of the children inquired “Are you never tired of seeing the same view?” and his laconic reply was “I never have seen the same view.”

Mr Alexander Dennistoun was returned to Parliament for the county of Dumbarton in 1835. He did not take kindly to Parliamentary life, and gave it up when Parliament was dissolved and never tried for a seat again. He was very silent, but Sir J. Colquhoun, who succeeded him, was still more so, and they were once described thus: “Mr Dennistoun always speaks when you ask him anything; Sir James never does.”

The life of the motherless children at Golfhill was an extremely quiet one. They were thrown entirely on their own resources, hut they seemed sufficient, and they never craved for more society or excitement. Robert had a good deal of mechanical skill, and he once made, out of a large wooden box, a sledge, which was christened “the Earl of Mar,” and when they came to the top of the hill the human horse was withdrawn and the guiding of it was exciting to them. He also constructed a little mill in which he ground real corn, which the girls baked into probably indigestible biscuits.

Prior to 1850 Golfhill, with the exception of the house and gardens, was all grass parks, which were left to freshers; but Mr Dennistoun, some few years after this, first thought of feuing the neighbouring ground. The whole was laid out in streets, terraces, and drives, and watching the growth, of this suburb was an inexhaustible source of interest to him. On his daughter one day saying to him she had seen in the papers the notice of two births in Dennistoun, he said: “Yes, you will see births and marriages, but no deaths—it is so healthy.”

It was Mr Dennistoun’s intention that it should be a model ‘suburb, with villas and gardens; but this was only partly carried out—at Westercraigs, Seton Terrace, and Oakley Terrace. Between these there is a pleasure ground and some trees, and the same between Clayton Terrace and Broompark Terrace. Craigpark and the west part of Onslow Drive is also included in “villadom.” The model suburb idea was not continued, as builders began to inquire for feus for tenements; and, as larger feu rents could be had from these and there was a good demand for houses of from two to five rooms and kitchen, new plans were prepared. Building then went on rapidly, until now most of the ground is covered with dwelling-houses.

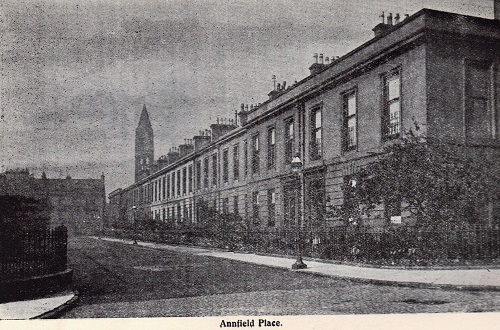

Before this scheme was carried out, however, Annfield Place was built—the first range of self-contained houses in the district. These houses have for many years been occupied mainly by doctors and ministers. At No. 11 there lived Dr G. R. Mather, a  public-spirited doctor who took a great interest in the various Exhibitions held in Dennistoun, and whose memory is kept alive by a bust which was placed in the People’s Palace in the Green by friends and admirers.

public-spirited doctor who took a great interest in the various Exhibitions held in Dennistoun, and whose memory is kept alive by a bust which was placed in the People’s Palace in the Green by friends and admirers.

There is a plot of ground between Annfield Place and Duke Street, within the old dyke which has been a great obstruction to the public, owing to the narrow pavement it allows at that part. Through the pressure of our local representatives in the Town Council, the Corporation are arranging now for the widening of Duke Street at this part, and the public may look forward to this needful improvement being carried out in the near future.

To come back to our history, Mr Alex Dennistoun, who projected the idea of the suburb, died in 1874, at the ripe age of 84, with his mental faculties absolutely undiminished and with the calm submission of an ancient stoic.

John, the youngest brother of Mr Alex Dennistoun—the “Uncle John” already referred to—was in nearly every respect a contrast to his brother. A thorough man of the world, with good social gifts, witty and very quick at repartee, he had travelled much and seen much of men and cities. In 1838 he married Frances, the youngest daughter of Sir Henry Onslow, Bart, (hence Onslow Drive). She was only 17, and it was a case of love at first sight, and he proposed to her within a week. She was very handsome, and had a wonderful fascination and charm. “She was so radiant, so impulsive, so unlike anyone I have ever seen,” says Mrs Sellar,” that I, as a child of 11, when she first came to Golfhill, became her abject slave.” They lived in London. There was a difference in age between Mr Alexander and Mr John Dennistoun of fifteen years, but they drew near to each other, and the last years of John’s life were spent at Armadale (hence Armadale Street), and there, in 1870, he died at the age of 66.

The husband of Mrs Sellar was, when they were married, assistant to Professor Ramsay in the Old. College in the High Street, and afterwards became Professor of Greek in St. Andrews University. Another member of the Dennistoun’ family married Mr Hensley Henson, now Bishop of Durham, one of the broad-minded men in the Church of England.

It will be seen that the founder of Dennistoun was careful to leave traces of the history of the Estate, for we have Wester Craigs, Craigpark Street and Drive, Golfhill Terrace arid Drive, Broompark Terrace and Drive, Whitehall, Street and Meadowpark Street—all names connected with estates and houses. Besides the names with family connections already given, we have Oakley Terrace, called after his son’s wife, Georgina Oakley, daughter of Sir Charles Oakley, Bart; and Roslea Drive, preserving the name of the country mansion at Roslea, Row, Dumbartonshire.

It might be mentioned here that behind Broompark Circus there is a little white house. In it was brought up Mr Hamilton McKenzie, R.S.W., one of lie well-known artist’s to-day in the West of Scotland.

With the reader’s permission we will now take a tour of the district, and will touch on Moss Street, a little to the east of Golf hill House. Before the modern villas were built, this was a narrow lane with a high embankment on either side. It therefore presented a very weird and fearful aspect, and was known to the boys as the “Devil’s Lane.” They used to go there now and then when they wanted a “thrill.” It seems that over forty years ago there was a huge stone built into the dyke, which was called the “Devil’s Stone” and every passer-by was supposed to throw a stone at this and run past. At the corner of Broompark Circus and Circus Drive there stands “Highfield,” the largest house in Dennistoun. It was built and first inhabited by a city merchant, who was a Magistrate. He had not long occupied it, however, when there came the great crash of the City Bank failure and its effect on the financial world. He then became a ruined man, and had to leave the house with his wife and family.

Going down Craigpark Street we come to No. 4 Craigpark Terrace, where a famous preacher of the old E.U. Church lived— Rev. Fergus Ferguson, D.D., who was one of the pioneers in the Temperance movement in Glasgow. The house at the corner of Craigpark Street and Oakley Terrace was, about thirty years ago, occupied by Sir William Arrol, the builder of the Forth Bridge and other great engineering structures, and founder of Sir William Arrol & Co., Ltd. He lived in Dennistoun when his works in Bridgeton were much smaller than they are now. He afterwards lived near Ayr, and represented South Ayrshire in Parliament for some years.

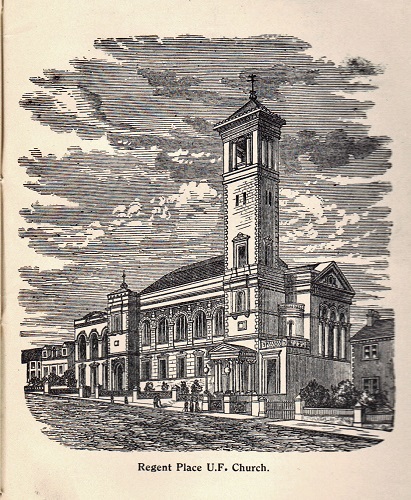

Nearby is Regent Place U.F. Church, which takes its name from a lane which used to connect Blackfriars Street with the Old Wynd at the High Street (now High Street Station). The best -known minister of this church was Rev. Dr Oliver, who was a Moderator  of the old U.P. Church. The large house at the corner of Annfield Place and Craigpark Street, on the right-hand side entering from Duke Street, and just below Dennistoun Public Library, was occupied for many years by Mr D. C. Glen of Greenhead Engine Works, who gathered together one of the best geological collections in the country. When he died, he bequeathed his collection to the Corporation, and it can be seen either at the Art Galleries in Kelvingrove or one of the district museums, and is known as “the Glen Collection.”

of the old U.P. Church. The large house at the corner of Annfield Place and Craigpark Street, on the right-hand side entering from Duke Street, and just below Dennistoun Public Library, was occupied for many years by Mr D. C. Glen of Greenhead Engine Works, who gathered together one of the best geological collections in the country. When he died, he bequeathed his collection to the Corporation, and it can be seen either at the Art Galleries in Kelvingrove or one of the district museums, and is known as “the Glen Collection.”

At No. 8 Clayton Terrace lives Rev. David Watson, D.D. minister of St. Clement’s Parish Church, one who has done a great deal in connection with Social Work for the Church. He has also published a number of books especially for young men and women, such as “In Life’s School” and ”Social Advance,” which are well worth a study.

Blackfriars Parish Church came to Westercraigs from College Open, off High Street, about the same time as Regent Place Church came east (1876-77). Black-friars Church dates back to 1622, when the city was divided into three parishes, and the Rev. Robert Wilkie was appointed the first minister. One of the succeeding ministers was the Rev. Mr Lockhart, father of Mr Gibson Lockhart, who married the daughter of Sir Walter Scott of Abbotsford, and who wrote the best biography of his father-in-law, the great novelist. The name “Blackfriars ” comes from the Monastery of the Black Friars which hundreds of years ago was situated near where High Street Station now stands.

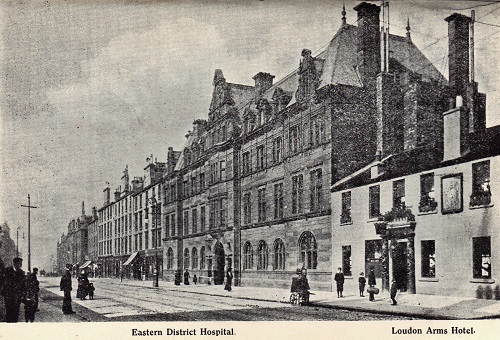

The late minister of Blackfriars Church —Rev. Thomas Somerville, D.D.—was in office when the removal took place from Blackfriars Street. As many will remember, he was known as “Rev. Tommy Somerville,” because of his personality. He was well liked by the people of the district, and was one of the most characteristic men Dennistoun has produced. Many years before his death he published a book entitled “George Square. Glasgow,” in which he tells the life-stories of the men to whom statues have been erected there, and this book will still be found interesting. The bell of this church used to ring at six in the morning as well as at six and ten in the evening, but this was discontinued when the Eastern District Hospital came to Dennistoun.

A few doors up Westercraigs, on the same side as the church, is to be found “Fern Villa,” one of the most interesting houses on the hill. In it lived for a great many years Dr Wm. Findlay, a local doctor who was often to be seen making his round of calls. Besides being a skilful doctor, he had literary gifts, and published a number of books under the nom-de-plume of “George Umber.” His most interesting book from our point of view is “My City Garden,” for in it he describes the garden behind his house in Westercraigs, and gives expression to has thoughts and experiences whilst resting there. Here is a description of the garden, followed by an experience which shows he was a very imaginative man:—

“My garden is bounded on the north and west and south by a red brick wall, and on the east by the house itself, past the gables of which the trees in the front plots thrust .their leafy arms and so shut out the view of the street. All ‘around the brick walls are trees and ferns and some (not always) flowers, and against an angle of the back of the house is an apple tree which has blossomed for the last two Mays, but never borne fruit; while a Virginia creeper climbs up the brick wall of a back jamb, past the parlour window, and loses itself among the dove-cots.

“The centre of the garden, which is rectangular in shape, is all laid out in grass, around which are gravel walks, and rising in the midst of one of the sides of the right angle is a conical-shaped rockery with a fountain on the top for the pigeons to drink out of and bathe themselves in. My summer seat occupies the south-west corner, where the trees were tallest and the branches most thickly interlacing. Here I sit and smoke and read, or dream and doze, or oftenest look idly from me, shaded from the sun’s hot glance and, what is of equal importance to a recluse like myself, hid from the prying view of my neighbours.

“I am not overlooked, which is more than I can always reckon upon even in the country gardens to which I betake myself for a month’s holiday in summer. The branches of my neighbour’s trees and mine embrace and link their arms together above the coping of the wall, and that is about the extent of our intercourse, nor do we seem to have any desire for more.

“A small field as yet unbuilt upon, and used by the cattle people in the district for grazing purposes—enfolds itself like a rich green carpet between my western wall and the huge block of tenement houses beyond, and through the open end of one of the streets I can not only see the summit of the Necropolis, bristling with its sculptured memorials of the dead, but all down its ivy-clad precipice to the more recently laid out holm on the Old Quarry side.

“This little bit of green level plain, already white with monumental granite, has more fascination for me than any other spot on earth, for it is there that my dearest little girl lies buried. I used to think, when walking through some gentle-man’s -policies and seeing the family burying-place in the grounds, that such a daily reminder of one’s mortality would be most disconcerting.

“Since then I have materially altered my opinion on that subject. My little girl’s burying-place, where I expect to be myself someday, is not as far from my dwelling-house as many a nobleman’s mausoleum is from his castle. Though it is but a step, so to speak, between the Necropolis arid where I sit in my City Garden, smoking and musing and looking idly from me, my little girl visits me dressed in her weeds of dusky death. There is not the remotest suggestion of mortality about her as she comes tripping round the house-end and like a perfect vision of delight runs across the grass and down the gravel walk to where I am sitting.

“She wears the lilac-spotted frock and white pinafore that she used to look so bonnie in, her shapely ankle and foot springing so lightly from the daisied turf that I was wont to admire so is more ravishing to my heart this afternoon than ever. I slip my arm round her and toy with her, and as I listen to her artless chatter I feel getting as weak as water in the young Cleopatra’s hands. She can ‘wile any mortal thing out of me,’ so her mother says, nor am I disposed to deny it. She catches my big rough hand in her tiny, soft one and with hysterical explosions of laughter directs it into my breeches pocket, where, to tease her by keeping her in suspense, I search leisurely, watching as I do the fun dancing in her eyes by my side, with a convenient crystal teardrop. And as I withdraw the longed-for coin, and still hold it in my shut hand, which between half-laughing and crying and pleading she struggles all out of breath to force open, the thought passes through my silly noddle that should I ever grow to be an old man—and, which God forbid! my wife dead—I would sooner live with this wilful little witch of a girl, if she were married and had a home of her own, than with any other child I have. She is not dead, not even sleepeth, nor will she ever be until I have ceased to remember her, which I pray Heaven to defend me from and that it may be mine, when I am laid in the ground beside her, to have an immortality in the hearts of those I leave behind as she has in ours.”

Then follows this description of a street cornet-player, whom I remember well myself playing, late in the evening, in Duke Street:—” Sounding clear and shrill above the rattle of chariot wheels and murmur of voices down in the main street (Duke Street), I hear the pathetic wail of a brass instrument. Ha! it is my old friend the cornet player. Now for a selection of fine old Scottish airs. He has started, I hear, with that ever-popular favourite ” Auld Robin Gray,” Whose sorrow-laden notes are piercing the moonlit air with swords; and for the next hour he will glide from it to ” My Nannie’s Awa’,” ” 0′ a’ the airts,” ” Jessie, the Flo’er o’ Dunblane,” ” Gloomy winter’s noo awa’,” —though it was just setting in—and back to “Auld Robin Gray.” Though I cannot see his farm, I know that he is standing there in the main street, just a foot or so off the pavement opposite S….’s spublic-house door, where I have seen’ him many a time as, passing along the street at night, I have lingered for a few minutes to watch his still figure and enjoy a brief taste of his quality, so that he has gradually become in a sense to be, like Hawthorne’s ”Old Apple Dealer,” a sort of naturalised citizen of my inner world.”

I now conclude these excerpts with a short one, which can he, and still is, the experience of those who happen to have occasion to be in Duke Street, especially at an early hour on Sabbath morning: — “The subdued hum of the city traffic we may be said to have always with us, except on Sundays; and then, if the wind blows from the south-west, the chimes from the Tollbooth Steeple at the Cross come sweet and hallowed on the Sabbath-tempered senses.”

A son of Dr Findlay’s—(also William Findlay, who now lives at Hairmyres—is one of the best known artists in Glasgow, and has done some panels for the Corporation in the Municipal Buildings. His works are to be seen in most of the Art Exhibitions, and he is recognised to be a portrait painter of note and has received various important commissions in this line during recent years.

At No. 15 Westercraigs there were brought up two boys, sons of the Rev. Wm. Mackay, of Young Street Free Church. One of these boys—Sage by name—became afterwards the Rev. Sage Mackay, D.D., one of the foremost preachers in New York and minister of an important church. He died some years ago in the prime of life. The other son is the Rev. W. Mackintosh Mackay, D.D., Sherbrooke Church, Pollokshields, one of the foremost U.F. Church ministers, who has published several notable theological works.

About the same time, at No. 4 Westercraig’s, there lived Rev. Alex. Rattray, minister of Parkhead Parish Church, whose son, Wellwood Rattray, was an artist of high standing in the city, having executed many important works of art. He died, however, just when he had established a reputation.

At this period also, two brothers, Rev. Geo. Jeffrey, D.D., London Rd. U.P. Church, and Rev. Robert T. Jeffrey, M.D., Caledonia Road U.P. Church—both notable preachers—lived next door to each other at 27-29 Westercraigs—South and North Adelphi Houses, large semidetached villas. It was said that a door was made between these houses so that the two brothers could visit one another without coming out of their houses into the open air.

There has just recently been wiped out, in Duke Street, one of the oldest landmarks in the district—the Loudon Arms Hotel. The Glasgow to Edinburgh coach used to stop here in the days before railways, and the cattle-dealers put up at this hostel when  they came to attend the market. It has had’ to make way for an extension to the Eastern District Hospital. It is said that about the site of the Hospital was where “Robin Tamson’s smiddy” stood, of which the poet Alexander Rodger (who was a weaver and lived in the Drygate) sang, although the line “The smiddy stands beside the bum that wimples through the clachan” implies a site nearer his dwelling-place. This song was a great favourite with the generation that has passed. Rodger had not only the reputation of a poet in his day, but was also one of the foremost Radicals. He was one of the leaders in connection with the ”Harvie’s Dyke Right-of-Way Case” (at the Clyde side), which’ caused a great stir in Glasgow at the time. His body lies in the Necropolis, his grave being in a conspicuous position on the hillside behind the Ladywell, the monument having been erected by public subscription.

they came to attend the market. It has had’ to make way for an extension to the Eastern District Hospital. It is said that about the site of the Hospital was where “Robin Tamson’s smiddy” stood, of which the poet Alexander Rodger (who was a weaver and lived in the Drygate) sang, although the line “The smiddy stands beside the bum that wimples through the clachan” implies a site nearer his dwelling-place. This song was a great favourite with the generation that has passed. Rodger had not only the reputation of a poet in his day, but was also one of the foremost Radicals. He was one of the leaders in connection with the ”Harvie’s Dyke Right-of-Way Case” (at the Clyde side), which’ caused a great stir in Glasgow at the time. His body lies in the Necropolis, his grave being in a conspicuous position on the hillside behind the Ladywell, the monument having been erected by public subscription.

Between the brick buildings and) the Eastern Hospital was the site of a colony of weavers who made “Leno“cloth. The houses were two-storey high and were built of brick, the weaving shops being on the ground floor and the dwellings above. They were swept away to make room for cattle-sheds.

The Cattle Market, which is situated apposite, was transferred here, in 1818, from a little to the westward of the Trongate end of Stockwell Street, and has been enlarged again and again as the needs of the expanding city became greater. The market for buying and selling was in farmer times held on Mondays of each week (instead of Wednesday as now), and the gates were not opened until 12 o’clock on Sunday nights, for at that time it would have been considered to be breaking the Sabbath to let the beasts into the market before that hour. The consequence was that drovers and cattlemen had to remain outside, and Duke Street, Gallowgate, and the side streets were filled with sheep and cattle, to the annoyance of the residents in the neighbourhood.

We now come to the Dunchattan Street area. It seems that George McIntosh, about the beginning of the 18th century, feued or bought 17 acres, of land, surrounded it -with a wall, and called it ” Dunchattan.” Mr McIntosh built a villa on the highest part of the hill for himself and family, and called it Dunchattan House,” situated about the position of Eveline Street, and approached by an avenue of trees from Duke Street, the line of this avenue being now Dunchattan Street. This house was taken down about fifty years ago. Mr McIntosh was the proprietor of dyeworks—then called “Cudbear Works”—situated a little to the west of his house. The word “Cudbear” comes from Dr CUTHBERT Gordon, who first brought into notice the purple or violet-coloured powder used for dyeing violet, purple, and crimson, prepared from various species of lichens. Mr McIntosh built a number of houses for the workers, all of whom were Highland people.

It was a Highland colony, none being employed unless they spoke the Gaelic. The streets off Dunchattan Street are named after family connections of the McIntosh’s. Mr George Eyre Todd, in his “Story, of Glasgow,” gives us some interesting information about Mr Charles McIntosh, son of George McIntosh, who was one of the pioneers of the important chemical industry in Glasgow and district. Besides his father’s factory, there had been introduced at Barrowfield—by a French chemist, Papillon—an ancient Indian process of dyeing cotton a fine colour known as Turkey red, and out of this industry soon developed others. In some of the processes of dyeing it was found difficult to attach the cloth to make it “fast “as it is called. In order to produce a fast dye it was necessary to discover a substance which would have a strong attachment for the cloth on the one hand and for colour on the other. Such a substance or “mordaunt,” was found in the salt we know as alum

This salt was discovered in the neighbourhood of Glasgow by Charles McIntosh. At Hurlet, on the Levern, near Barrhead, were certain mines where waste shale was of a peculiar character. After lying for a time exposed to the weather, a hard stony material was seen to split into thin leaves and become studded with crystals. This waste attracted the notice of Charles McIntosh. He experimented with it, and found that by dissolving the crystals in water with another chemical and boiling down the solution he got the whitish astringent substance we know as alum.

This alum was exactly what was wanted as a mordaunt by the dyers. It was also of great use for making the lake colours used by artists, and out of its manufacture grew the great industry carried on yet by the Hurlet and Campsie Alum Company. The process of manufacture was soon shortened by roasting the shale instead of leaving it to the weather, and the discovery made by Charles McIntosh has been the means of employing large numbers of men and built up more than one great fortune.

Still another of Charles McIntosh’s services to Glasgow was the introduction of the manufacture of sugar of lead. Before 1786 this substance was altogether imported from Holland Charles McIntosh found out the secret of the manufacture, set up works in Glasgow, and very soon was exporting considerable quantities to Rotterdam, the actual place where he had learned the secret. It was the same Charles McIntosh who invented the process of making rubber-coated waterproof cloth, still called by his name “Macintosh” and he carried on the industry first in Glasgow.

Peter McKenzie says that Mr McIntosh was materially aided; by Mr Eneus Morrison, writer in the city, in his original application of caouteha to linen, cotton, and other fabrics, which led to the introduction of the first famous “Macintosh ” waterproof.

It is singular to relate that the first waterproof made in Glasgow by Mr McIntosh was presented by him to Mr Morrison. The latter went out to Bucklyvie Moor to shoot grouse one summer, on the 12th August. He bagged his game plentifully, and was as merry as any man could be on such an occasion, the perspiration falling off his face. The waterproof (which was the first and last he ever had), it was thought, prevented the free circulation through other parts of his body and he was brought back to Glasgow almost senseless and died very soon afterwards.

I came across the interesting fact recently that Sir John Moore, the hero of Corunna, who was born in the Trongate, was a nephew of Mr Geo. McIntosh. He was educated partly on the Continent, and took up the Army as a profession. When appointed Paymaster to the Hamilton Regiment he was taken by his uncle into the counting-house of his works—the Cudbear Works—to learn book-keeping, so as to obtain’ the necessary experience to fit him for the post he was about to take up. Moore Street, opposite Dunchattan Street, is thus accounted for.

Let us now walk along Duke Street to Hillfoot Street, up from which is situated a notable landmark — the old Reformatory Buildings, which used to be approached from Duke St. through an iron gateway and by means of a long avenue of trees. This Reformatory was built in 1836, at a cost of £13,000, raised by public subscription, and is in the Italian style of architecture. In it juvenile offenders and neglected’ children were given a good education and trained to self-support. It usually had about 300 inmates. Its use for this purpose was discontinued many years ago, and it lay empty for some time. However, over 30 years ago, when through the malicious act of some boys the training-ship “Cumberland,” stationed opposite Row, in ‘the Gareloch, was set on fire and burnt to the water’s edge, until the new ship “Empress” was ready for occupation, the boys lived in the old Reformatory Buildings.

The only use they have since been put to has been in connection with a few of the Exhibitions which have been held on the grounds. ”Buffalo Bill” and his ” Wild West Show” was also held here one winter, and at that time the Red Indians were to be met making their purchases in Duke Street, etc., with their coloured faces and brightly-coloured shawls. Blondin, when an old man (who had crossed Niagara Palls with a wheel-barrow), appeared at one of the Exhibitions and walked on a tight-rope with a man on his back across the building.

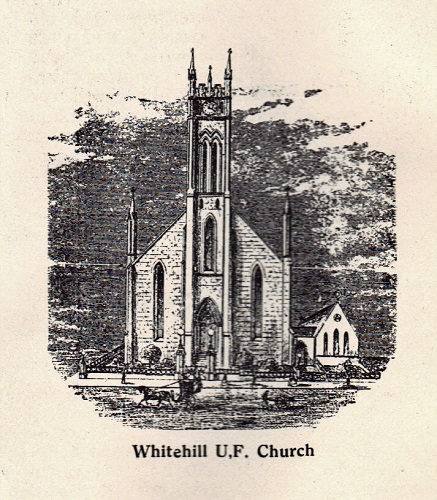

Continuing along to Whitehill Street, beside Whitehill U.F. Church is the house where Sir Andrew H. Pettigrew, J.P., managing director of Pettigrew & Stephens, Ltd., and Stewart & McDonald, Ltd., also chairman of the Scottish National Council of Y.M.C.A.’s  lived when a lad. There lived at No. 268 Whitehill Street, until his death a few years ago as a result of a car accident, Mr Thomas Lugton, curator of the People’s Palace. He was much interested in all pertaining to Old Glasgow, and published a book “The Old Ludgings of Glasgow,” in which he tells all that can be discovered in connection with the Pre-Reformation Manses used by the clergy of the Cathedral in the old days on the banks of the Molindinar Bum, the Drygate, &c.

lived when a lad. There lived at No. 268 Whitehill Street, until his death a few years ago as a result of a car accident, Mr Thomas Lugton, curator of the People’s Palace. He was much interested in all pertaining to Old Glasgow, and published a book “The Old Ludgings of Glasgow,” in which he tells all that can be discovered in connection with the Pre-Reformation Manses used by the clergy of the Cathedral in the old days on the banks of the Molindinar Bum, the Drygate, &c.

Robert Grahame, who was proprietor of the lands of Whitehill at one time, was a gentleman of some importance, and was Provost of Glasgow 1833-34. He was one of the members of the Reform Association instituted by Mr Thomas Muir of Huntershill, who was transported to Australia for the Radical opinions he held. Mr Grahame was a friend of Baird and Hardie. Perhaps this can be accounted for by the fact that Hardie lived at the corner of Duke Street and High Street. Baird and Hardie gathered together 100 weavers and mechanics one dark night in 1820 on the Fir Park. They were supplied with guns and told to walk towards Falkirk, on a promise that they would be met there by thousands of English comrades and would then take possession of the cannon at Carron Iron Works, with which they were to return to Glasgow in triumph. However, their company was met by Government troops before they arrived at Falkirk and after making a stand they were mostly taken prisoners.

Baird and Hardie were tried and put to death at Stirling for treason, and their bodies were afterwards removed to Sighthill Cemetery, where a monument was placed over their tomb. When Baird and Hardie were condemned Mr Grahame posted to London, leaving his important business for the purpose of interceding with the Government for their reprieve, but unfortunately without effect. Mr Grahame was universally esteemed by men of all parties as a gentleman of the highest reputation. Whitehill Houses in which Mir Grahame lived, used to stand below Garthland Drive, in Whitehill Street, and bad been occupied by other two famous Glasgow families—the Glassfords and the Wallaces.

Craigpark House, belonging to James McKenzie, who was also a Provost of Glasgow, stood about the top of Whitehill Street, above Onslow Drive, and was a fine old mansion. About 1820 he allowed the sharp-shooters of the town to practise at a rifle target in the whinstone quarry on his estate. It was considered a great feat in those days to pierce at a distance of 70 or 80 yards the rifle target with the bullet through the bull’s-eye. In later years, it is said, the house was occupied by a Mrs Fairlie as a private school for young ladies. The stables were on the north side of what is now Alexandra Parade, and were let to a MR Cullen for some years, who farmed the ground of Golfhill, Craigpark, and Whitehill.

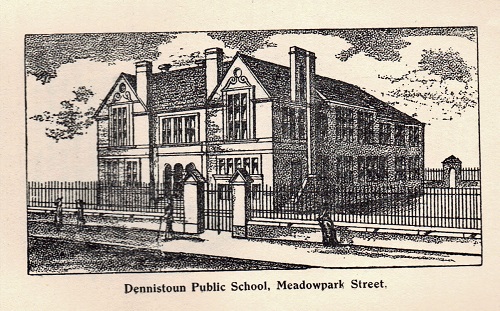

We now pass along to Meadowpark Street. Near Ingleby Drive—about the Golfhill Cricket Club pavilion site—there stood Meadowpark House, from which the street took its name.

At 142 Ingleby Drive there lived, in the same close and at the same time, about a quarter of a century ago, two gentlemen who were known as writers of some repute, one being Robert Ford, who held a position with Messrs J. & W. Campbell & Co., and who died quite a number of years ago. He wrote prose and poetical pieces suitable as readings, besides publishing various books with selections of pieces for this purpose, his best-known hook being “Thistledown,” a selection of Scotch humorous stories. He also issued a selection of the best poems, entitled “Poems and Songs of Bairnhood,” and a book giving the history of the Chief Songs of All Nations, which appeared first in the “People’s Friend.” There is one reading of his which will live— “The Deputation.” It is the story of a deputation of church elders waiting on their minister to reprimand him for playing the fiddle in the manse, but they come away from the interview quite reconciled owing to the fascination of the minister and his fiddle upon them. A bust of Mr Ford has been placed in his memory on his grave in Sandymount Cemetery, Shettleston.

The other gentleman who lived at 142 Ingleby Drive was Mr Alexander Lament, for some time headmaster of the school in Campbellfield Street. He wrote to the ”Quiver,” “The People’s Friend,” and other periodicals, under the nom-de-plume of “The Vicar of Deepdale.” These pieces were of the same calibre—of a high literary character, and were descriptions chiefly of Nature in her many moods and his communings with it in relation to life.

At 101 Armadale Street there lived, a number of years after his marriage, Sir John Hunter, K.B.E., nephew of Sir Wm. Arrol.

East of Whitevale’ Street—which was to be a fashionable street—in 1828 there was a large nursery, in which all manner of vegetables and flowers grew. In Whitevale Street, after this time, there were twelve self-contained houses—six on either side—which were mostly occupied by ministers and were called “The Twelve Apostles.”

Between Whitevale Street and Bellgrove Street there were four mansion-houses only—Annfleld House (hence Annfield Street), belonging to James Sword (hence Sword Street); Bellfield House (hence Bellfield Street), belonging to Mrs Gillies; Slatefield House (hence Slatefield Street), belonging to Mr Cubic; and Comelypark House (hence Comelypark Street).

At one time there was some brick making on a portion of the grounds, and Mr Thomson (hence Thomson Street), of Annfield Pottery, took all the clay from the Annfield portion for the making of his coarser ware.

In Bellgrove Street, below the Cattle Market, there lived, about thirty years ago, beside his bakery (which entered from the wide pen), William Beattie, who founded the Dennistoun Bakery (now transferred to Paton Street), considered to be one of the most modern bakeries in this country. Mr Beattie, after being a herd boy in Ireland, came to Glasgow at 13 years of age and worked as a baker at several shops. He then commenced business on his own account and after a successful business and public career he died 7th April, 1919, at his residence overlooking the waterworks at Milngavie.

Bellgrove at one time was a narrow road, with a row of trees down each side and a small ditch running from Duke Street to Gallowgate., It was then called “the Witch Loan”; and on the east of it, at the top, stood Annfield Park, which contained the large black Annfield House, with stone lions of each side, which was said to be haunted by a white lady. On the west side of Bellgrove were a number of villas, with gardens running back to the wall of the Cattle Market. When the infantry were in the Barracks in the Gallowgate, some of the married officers lived here with their wives and families. On holiday evenings, such as Queen Victoria’s Birthday, Bellgrove Street was crowded, as it was the recognised centre of the district, and there was a display of fireworks.

Going up Meadowpark Street to Alexandra Parade, we come to the street, a little eastwards, which used to be called ” Kaiser ” Street but was altered during the Great War to “Marne” Street—to commemorate the turning-point in the war-in the Allies’ favour.

We will finish our ramble with a visit to Alexandra Park. This park was opened by King Edward and Queen Alexandra in 1870 (when they were Prince and Princess of Wales), thus the name Alexandra. Mr Dennistoun of Golfhill gave an additional five acres to this park so as to connect it with the projected street called Alexandra Parade, to connect Castle Street with Cumbernauld Road; the area of the park was occupied formerly partly by a distillery. Recently the Corporation has transferred to it “The Macfarlane Fountain” from the Kelvingrove Park.

From the flagpole on a clear day there is an extensive view—on the south side, from Tinto down the valley of the Clyde to near Paisley, embracing Dechmont, Cathkin, Gleniffer, Neilston Pad, and many other high grounds. On the north side there is a view of the Campsie range, along to Strathblane, and beyond that Ben Lomond. In fact, on a very clear day, the mountains on Loch Long side can be seen.

To the north of Alexandra Park is the Old Monkland Canal, which extends from Port Dundas to the district of Old Monkland, where it sends off four branches to various ironworks.

It was projected in 1769, the survey of the ground being carried out by James Watt of steam engine fame, who in his earlier days was scientific instrument maker to the Old College in High Street and later practised as a civil engineer in Oswald Street, City.

The locks at Blackhill, to the north-east of the Park, are of a character that they stand out in comparison with works of their class in Great Britain. These looks are composed of two sets of four double locks, each being worked independently of the other. They were formed at an expense of £30,000.

In 1850, owing to increase of traffic, an inclined plane with rails was formed, at an expense of £13,500, by Which empty boats were taken up at a saving of five-sixths the water and nine-tenths the time. Each boat was conveyed afloat in a caisson, up an incline of 1040 feet, and the traction was carried out by steam power and rope rolls. This inclined plane has not now been in operation for many years, but it is only a few years since it was removed, it having remained as a landmark during this time. The Monkland Canal was taken over in 1867 by the Caledonian Railway Company.

The Poets

of

Dennistoun

James Grahame

JAMES GRAHAME, who attained fame at the beginning of last century as the author of the poem “The Sabbath,” was a brother of Robert Grahame, at that time proprietor of Whitehill, and for a term Provost of Glasgow.

James Grahame, who was born in Glasgow on 22nld April, 1765, died at his brother’s residence at Whitehill on 11th October, 1811.

When a boy at school, he received a blow on the back of the head, and this rendered him delicate throughout life and subject to frequent attacks of headache and stupor—in fact was the cause of his death in the end.

He became a Writer to the Signet, but his health failing he two years afterwards passed into the Faculty of Advocates. He published at this time several poems, including “Mary Stuart: an Historical Drama,” but these attracted little notice. He therefore determined, when he had another poem ready for publication, he would keep it secret. When the proofs of the new poem arrived, he corrected them in coffee-houses, as he did not desire even his household to know. When the book containing “The Sabbath” was ready, he took a copy home and left it on the table. On returning to the room later, he found his wife deeply interested in perusing the volume. He walked up and down feeling anxious, but said nothing, and at last she exclaimed “Ah! James, if you could only write like this.” Sometime after the publication of this book he determined to carry out an early desire, and proceeded to London and entered the English Episcopal Church, holding in succession the curacies of Shefton Mayne in Gloucestershire, of St. Margaret’s, Durham, and of Sedgefield. His health rapidly declined, and he came to Glasgow and passed away at Whitehill House.

The opening lines of the poem are as follows.—

THE SABBATH

How still the morning of the hallowed day!

Mute is the voice of rural labour, hushed

The ploughboy’s whistle and the milkmaid’s song

The scythe lies glittering in the dewy wreath

Of tedded grass, mingled with fading flowers

That yestermorn bloomed waving in the breeze.

Sounds the most faint attract the ear—the hum

Of early bee, the trickling of the dew,

The distant bleating, midway up the hill

Calmness seems throned on yon unmoving cloud.

To him who wanders o’er the upland leas

The blackbird’s note comes mellower from the dale,

And .sweeter from the sky the gladsome lark Warbles bis heaven-tuned song: the lulling brook

Murmurs more gently down the deep-sunk glen;

While from yon lonely roof, whose curling smoke

O’ermounts the mist, is heard at intervals

The voice of psalms, the simple song of praise

With dove-like wings, peace o’er yon village broods;

The dizzying millwheel rests; the anvil’s din

Hath ceased: all, all around is quietness

Less fearful on this day, the limping hare

Stops, and looks back and stops, and looks on man,

Her deadliest foe. The toil-worn horse, set free,

Unheedful of the pasture, roams at large,

And, as his stiff unwieldy bulk he rolls,

His iron-armed hoofs gleam in the morning ray.

But chiefly man the day of rest enjoys.

Hail, Sabbath! thee I hail, the poor man’s day!

On other days the man of toil is doomed

To eat his joyless bread, lonely, the ground

Both seat and board, screened from winter’s cold

And summer’s heat by neighbouring hedge or tree.

But on this day, embosomed in his home,

He shares the frugal meal with those he loves:

With those he loves he shares the heartfelt joy

Of giving thanks to God—not thanks of form,

A word and a grimace, but reverently,

With covered face and upward, earnest eye.

Hail, Sabbath! Thee I hail, the poor man’s day.

The pale mechanic now has leave to breathe

The morning air pure from the city’s smoke,

While, wandering slowly up the riverside,

He meditates on Him whose power he marks

In each green tree that proudly spreads the bough,

As in the tiny dew-bent flowers that bloom

Around the roots. And, while he thus surveys

With elevated joy each rural charm,

He hopes, yet fears presumption in the hope,

To reach those realms where Sabbath never ends

It is not only in the sacred fane

That homage should be paid to the Most High.

There is a temple, one not made with hands,

The vaulted firmament. Far in the woods,

Almost beyond the sound of city chime,

At intervals heard through the breezeless air:

When not the limberest leaf is seen to move,

Save when the linnet lights upon the spray;

Where not a floweret bends its little stalk,

Save when the bee alights upon the bloom;

There, wrap in gratitude, in joy, and love,

The man of God will pass the Sabbath noon,

Silence his praise, his disembodied thoughts,

Loosed from the load of words, will high ascend

Beyond the empyreal.

Alexander Rodger

ALEXANDER RODGER, “the Radical poet, “author of “Robin Tamson’s Smiddy” and other songs and poems (referred to on page 26) was born at East Calder on 16th July, 1784. The family removed to Edinburgh when he was about twelve years of age, and he was apprenticed to a silversmith.

His father, however, becoming bankrupt in his business and disappearing to Hamburg, Alexander Rodger, along with other members of the family, was brought to Glasgow by his mother’s friends and was apprenticed to a weaver in the Drygate. In 1806 he married Agnes Turner, and lived for a time in the then village of Bridgeton.

In order to support a growing family, he went in for music teaching as well as weaving. In 1821 he received employment as an inspector of cloths at Barrowfield! Print Works, and it was during this period the most of his songs and poems were written.

In 1832 a friend, (having commenced business as a pawnbroker, arranged with Rodger to become manager, but in a few months he gave up this position). He afterwards became a reporter on one after another of Glasgow’s newspapers, and was engaged in that capacity on “The Reformer’s Gazette” (Peter Mackenzie’s paper) when he died on 26th September, 1846. He used to appear often at the Saturday evening concerts in the City Hall and in a genial way sang some of his own songs.

ROBIN TAMSON’S SMIDDY

My mither men’t my auld breeks,

And wow, but they were duddy

And sent me to get Mally shod

At Robin Tamson’s smiddy

The smiddy stands beside the burn

That wimples .through the clachan;

I never yet gae by the door

But aye I fa’ a-lauchin’.

For Robin was a walthy carle,

And had a bonnie dochtar;

Yet ne’er wad let her tak’ a man,

Though many lad’s had socht her.

And what think you o’ my exploit?

The time the mare was shoein’

I slippit up beside the lass,

And briskly fell a-wooin’.

And aye she e’ed my auld breeks,

The time that we were crackin’

Quo’ I, “My lass, ne’er mind the clouts,

I’ve new anes for the makin’.

But gin ye’ll just come hame wi’ me,

And lea’ the carle, your faither,

Ye’se get my breeks to keep in trim,

Mysel’ and a’ the gither.”

“Deed lad,” quo’ she, “your offer’s fair,

I really think I’ll tak’ it;

Sae gang awa’, get out the mare.

We’ll baith slip on the back o’t.

For gin I wait my faither’s time

I’ll wait till I be fifty;

But na, I’ll marry in my prime,

And mak’ a wife fu’ thrifty.”

Wow! Robin was an angry man

At tymin’ o’ his docbter;

Through a’ the kintra-side be ran,

And far and near be socht ber;

And when be cam’ to our fire-end,

And fand us baith thegither,

Quo’ I, ” Gudeman, I’ve ta’en your baim,

And ye can tak’ my mither.”

Auld Robin girned, and shook his pow:

“Gude sooth,” quo’ he, “you’re merry,

But I’ll just tak’ ye at your word,

And end this hurry-burry.”

So Robin and our auld wife

Agreed to creep thegither;

Noo I ha’e Robin Tampon’s pet,

And Robin has my mither.

William Miller

” The Laureate of the Nursery.”

There lived in a house at No. 4 Ark lane (on the site now occupied by Fulton’s Engraving Works), for many years, William Miller, author of “Wee Willie Winkie,” ” A Wonderfu’ Wean,” ” Gree, Bairnies. Gree,” “The Sleepy Laddie,” ” John Frost,” and many other poems.

Miller was born in Glasgow in August. 1810, arid spent most of his boyhood in the then adjacent village of Parkhead. His earliest inclinations were in favour of surgery as a profession, and he studied for some time with that view, but a serious illness when he was about sixteen years of age prevented this intention being carried out. He then became an apprentice woodturner, and in this craft he became a skilful workman, cabinetmaking being his particular line. It is stated that even in his later years there were few who could equal him in speed and excellence of workmanship. Wood-turning continued to be the business of his life, and he wrought at it until within a few months of his death.

A lady who still lives nearby remembers William Miller going out and in from his home always wearing a tall hat, except during working hours. He was by chance a wood-turner, but by nature he was a poet, and early in life he began to write songs and poems, his best-known being, of course, “Wee Willie Winkie,” which I will quote in full for the benefit of those not conversant with it—viz.:

Wee Willie Winkie rins through the toon

Upstairs and downstairs in his nicht-gown,

Tirlin’ at the window, crying at the lock,

Are the weans in their bed, for it’s now ten o’clock?

Hey, Willie Winkie, are ye comin’ ben?

The cat’s singing grey thrums to the sleepin’ hen,

The dog’s ispeldert on the floor and disna gie a cheep,

But here’s a waukrife laddie that wunua fa’ asleep!

Onything but sleep, you rogue! glowerin’ like the moon,

Battlin’ in an aim jug wi’ an aim spoon;

Rumblin’, tumblin’ roon about, crawin’ like a cock,

Skirlin’ like I kenna what, wauk’nin sleepin’ folk.

Hey, Willie Winkie—the wean’s in a creel,

Wamblin’ aff a bodie’s knee like a verra eel,

Ruggin’ at the cat’s lug and ravelin’ a’ her thrums,

Hey, Willie Winkie—see, there he comes!

Wear-it is the mither that -has a stoorie wean,

A wee stumpie stousie that canna rin his lane,

That has a battle aye wi’ sleep afore he’ll close an e’e

But a kiss frae aff his rosy lips gi’es strength anew to me.

Robert Ford, who published an edition, of Miller’s songs and poems in 1902, says of him:—” As surely ‘as Blake and Wordsworth gave the turn to naturalness in England, as surely as Robert Bums- gave a new bent and sweeter, tenderer music to the love songs of his country—as surely did William Miller set a new light in the Scottish Nursery, at which nearly every subsequent singer has lit his taper.”

Miller’s poem ” A Wonderfu’ Wean ” was written in regard to his only child Stephen, and as it is often given yet as a leading at children’s parties I will quote a few verses—viz.:

Our wean’s the most wonderfu’ wean e’er I saw,

It would tak’ me a lang summer day to tell a’

His pranks, frae the morning till night shuts his e’e,

When he sleeps like a peerie ‘tween father and me;

For, in his quiet turns, siccan questions he’ll spier

How the moon can stick up in the sky that’s sae clear?

What gars the wind blaw? and whar frae comes the rain?

He’s a perfect divert—he’s a wonderfu’ wean

Or wha was the first bodie’s father? and wha

Made the very first snaw-shower that ever did fa’ ?

And what made the first bird that sang on a tree?

And the water that sooms a’ the ships dm the sea?—

But after I’ve told him, as weel as I ken,

Again be begins wi’ his wha? and his when?

And he looks aye sae watchfu’ the while I explain,

He’s as auld as the hills—he’s an auld-farrant wean!

But ‘mid a’ his daffin, sic a kindness he shows

That he’s dear to my heart as the dew to the rose;

And the unclouded hinnie-beam aye in his e’e

Mak’s him every day dearer and dearer to me.

Though Fortune be saucy, and dorty, and dour,

And gloom through her fingers, like hills

through a shower,

When bodies hae got a bit bairn o’ their ain,

How he cheers up their hearts—he’s a

wonderfu’ wean!

Miller was laid aside with illness in the winter of 1871, but although his body was weak his intellect was vigorous, and be continued to write poems, which appeared in the “Scotsman,” “The People’s Friend,” and elsewhere. Previous to this—in 1863— he issued what is now an exceedingly rare collection of ” Nursery Rhymes and Poems,” when his reputation as an author became rapidly known. Through the winter 1871-72 his illness continued, and in the spring his friends had him removed to Blantyre. As he was not recovering, and the end seemed near, be was brought to his son’s house in Glasgow—at his own request —and there he passed quietly away on the 20th August, 1872, having just completed his 62nd year. He was buried in the family burying ground, at Tollcross, a monument, however, being erected by public subscription in the Glasgow Necropolis, commemorating him as ” The Laureate of the Nursery.”

Alexander Anderson (” Surfaceman”) wrote these appreciative limes on William Millar, viz:

He only sang of home and hearth,

No higher pinion has his song,

His voice was blent with childhood’s mirth,

When nights were dim and rich and long;

Yet what a rare reward and sweet

Is his, for, by his lowly art

The sound of “Willie Winkie’s ” feet

Is heard in every mother heart,

Robert Buchanan, the novelist, has said that “wherever Scottish foot has trod, whenever Scottish child has been born, the songs of William Miller have been sung. I can scarcely conceive a period when William Miller will be forgotten; certainly not until the Doric Scotch is obliterated.” Another writer says truly that it is not so much in his touches of tenderness as in his dramatic appreciation of the life of the nursery that William Miller excels.

William Miller’s widow continued to live at No. 4 Ark Lane a number of years after his death, and was known as “Cat Jean,” ‘as she was a great lover of cats. She gathered all the stray and homeless cats into her home—sometimes to the number of a dozen—and took an interest in looking after her dumb charges.

Alexander Falconer

ALEXANDER FALCONER, born in 1834, was a native of the Calton, and was the son of a stone mason. Having received schooling until the age of nine, he was then apprenticed to a chemist. He early acquired a taste for book’s, and was often to be found reading one of these in an attic attached to the house. When twenty years of age be received the appointment of a reporter on the staff of a Glasgow newspaper, and in this capacity made the acquaintance of various literary men of note.

Journalistic work, as then practised, did not suit him, and be turned to look for another opening. After assisting for some time in the Reformatory in Duke Street as a Sunday teacher, then in 1857 was appointed to the permanent staff. Owing to his early experience as a chemist, and having surgical knowledge, he was known to the boys as “the doctor.”

Thereafter he held appointments in Greenock, Belfast, and Sunderland. He then returned to Glasgow as Governor of the Buys’ Industrial School at Mossbank, and held this position for twenty-seven years. Throughout his life-work in connection with these reformatories, Falconer substituted

more gentle means of dealing with these difficult youths than, this methods of repression previously adopted—such as the lash and the cell—and in this way it was found that about 90 per cent, of those trained under him did well in after life.

Falconer was very much interested in literature during his life, and was a great admirer of Wordsworth. He published a volume, “Scottish Pastorals and Ballads,” in 1894, and died two years later, in 1896.

Here is one of his gems:—

WEDDED LOVE

We went by the com and barley,

And the woodland ways so sweet, so sweet;

The linnet arid the mavis sang all the way,

And the river that flowed at our feet

There was love in the bush and love in the blue,

And the sunshine laughed, and the shadows flew,

As if each knew

‘Twas our twentieth marriage morning

By the stile half hid ‘mong the rowan and thorn,

Where the old wooden bridge and the kirk tower are seem,

And all the clear length of the water that lies

In the silvery shadows between,

We stayed’, and, fondly as true lovers, kissed—

Kissed, for ‘twas here long ago I was blessed;

While our eyes were filled with a sudden mist,

On our twentieth marriage morning

Then she pulled a flower from brier and thorn,

And; set each, as she only could, in her hair,

“And now, beloved, come tell me true,” She said with her winsomest air,

“Not so bonnie as then?

Not so bonnie as when

I drooped, while you cheerily said ‘ Amen,’

And we passed out with blessings that morning?

Not so bonnie nor blythe, I am sure, you’ll say,

As in the dear courting time, long ago,

When you praised, you remember, my simple ways,

My eyes and my ringlets then black as the sloe?

Not so blythe as then—

Not so blythe as when

I drooped, while you cheerily said ‘ Amen,’

And your love was your wife that morning?”

Oh, never so much of the gay-worded wit

Had I seen her, my darling, in bypast years;

And of many a gladness we both bad shared,

Of troubles enough, and tears,

Then love stirred anew

Love tender and true,

And while sunshine laughed and while shadows flew

I told all my heart that morning.

The flowers she took from her dark, tangled hair,

As I sang the last words, and twined them together,

And holding them up, said, with tenderest charm,

“Thus, love, have we been in all sorts of weather

In the past golden years,

And so we shall be, come what joys or what tears:

Take this as the token, I go without fears

On our twentieth marriage morning.”

Alexander G. Murdoch

ALEXANDER G. MURDOCH was born in the northern part of Glasgow in April, 1843. After receiving a meagre education he was early apprenticed to the trade of marine engineering, and was for a period thereafter employed by Messrs Singer. Without outside assistance he developed, a literary tent, and contributed many poems—especially humorous ones—to the “Glasgow Weekly Mail.” He was after a time able to publish a book of his poetry, and by 1879 he had issued three volumes of his poems. In this year he won the medal offered by the Committee of the Burns Monument at Kilmarnock for a poem on the Ayrshire Bard. After this he became a member” of the staff of the “Mail,” and wrote several serial stories— ” Fire and Sword,” “Sweet Nellie Gray,” “Bob Allan’s Lass,” etc.—besides issuing various other books, including “Recent and Living Scottish Poets.” It is as a poet, however, he will be remembered, as be had the real poetic chord in his nature. He died at his house in Bellgrove Street on 12th February, 1901.

T

THE BURNS MONUMENT, KILMARNOCK

I handle life’s kaleidoscope, and lo! as round it turns,

I see, beneath an arc of hope, the young boy-poet, Burns.

Dream-visioned, all the long, rich day he toils with .pulse of pride

Among the sun-gilt ricks of hay, his Nellie by his side

The world to him seems wondrous fair: sunrise and sunset fill

With music all the love-touched air, intoned in bird and rill,

Time moves apace: the ardent boy confronts life’s deep’ning fight,

And ” Handsome Nell “—a first-love joy—melts into memory’s light.

I look again, and shining noon still finds him chained to toil,

His soul throned with the lark song-poised above the daisied soil;

Mossgiel! upon thy greensward now the song-king grandly stands,

God’s sunshine on his face and brow, the plough-horns in his bands

Mouse that dost run with “bickering gait,” stay, stay thy trembling flight,

The bard who wept the daisy’s fate laments thy hapless plight,

And perchance, when the gloamin’ lies on glen and hillside green,

Thy mishap may re-wet his eyes, told o’er to Bonnie Joan!

Kilmarnock! Oft thy streets and lanes echoed the poet’s tread.

He brought to thee his matchless strains, asking for fame—not bread;

And see, the proud bard, dream-wrapt; stands for one sweet hour apart,

His book of song within his hands, and in his book—his heart!

O, happy town! that gave the bard a gift hope-eloquent,

His dearest wish and first reward—his book in ” guid black prent ”

And prouder throbbed his heart by far when that sample book he pressed

Than if a coronet >and star had decked him, brow and breast

The glass revolves again, and lo! Edina fair appears,

And men around him come and go, and

Rank a proud front rears; And Wealth and Fashion, gaily decked, look on with lofty eye,

While Learning, with a vague respect, bows as the bard goes by.

Mark him, ye great! The plough and clod befit him ill, I trow—

The living autograph of God flashed from his eye and brow.

The drama hurries on: the bard retires to Eilisland;

At plough and hairst-rig toiling hard—a toiler strong and grand,

A curbed Elijah, peasant-born, daring Song’s windy height,

His homely garb, clay-stained and worn, a prophet’s robe of light

His giant heart his only lyre, by Love’s rich breath oft stirred,

Till memory’s passion-gusts o- fire among its chords were heard.

And never from Eolian wires was holier music wrung

Than what his heart’s re-kindled fires at Mary’s grave-shrine flung.

The veil uplifts once more, and now, sublimest scene of all!

His lion-heart still strong, his brow erect, although the gall

And bitterness of trampled! hopes sadden his weary soul

As be, a stricken song-god, gropes towards the final goal.

Dumfries, no longer doth he tread thy stony streets, soul-tired—

The dark clouds settling o’er his head, by genius glorified.’

Ring down the curtain! Bow the head!

The last sad scene is o’er!

A nation mourns the mighty dead, and weeps the griefs he bore.

Sun that no shadow now can cloud! Heart that no sorrow wrings!

Man, in whose praises’ all are loud! Voice, that for ever sings!

A people’s love the holy bier that holds thy worth in trust,

With glory flashing through the tear that drops above thy dust;

O, rich inheritor of fame, rewarded well at last,

Whose strong soul, like’ a sword of flame, smites with fierce light the past,

This sculptured pile, in trumpet tomes, attests thy vast renown—

A nobler heirship than the thrones to princes handed down.

TOWN COUNCILLORS REPRESENTING DENNISTOUN AND DISTRICT

Dennistoun

Ex-Treasurer JAMES BARRIE

Councillor W. J. LOGIE.

Councillor Dr JAMES DUNLOP.

Whitevale

Ex-Bailie JOHN MDIR

Councillor JAMES MILLER.

Councillor ROBERT MACDONALD.

REPRESENTATIVE MEN IN DENNISTOUN,

All being Justices of the Peace

William Anderson, 1 Moss Street

Ex-Treasurer James Barrie, 7 Broompark Terrace

P. Beattie, 116 Paton Street.

Alexander Bennie, 3 Broompark Terrace.

William Brown, 621 Alexandra Parade.

Daniel Browning, 4 Clayton Terrace.

Richard Cathcart, 29 Roslea Drive

Parish Councillor James Cunningham, 2 Oakley Terrace

Robert Duncan, 551 Alexandra Parade.

John Dunn, 17 Westercraigs.

William Forsyth, 571 Alexandra Parade.

Parish Councillor Denis Hegarty, 275 Duke Street.

Ex-Bailie Thomas J. Irwin, 2 Broompark Circus

Councillor W. J. Logie, 9 Moss Street

James McDermid, 621 Alexandra Parade.

Ex-Preceptor James McFarlane, 294 Duke Street

Ex—Bailie Henry McNaughton, 101 Armadale Street

Dr Samuel McLean, 13 Armadale Street

James McVey, 5 Broompark Circus

John Morton, 116 Paton Street

Ex-Bailie John Muir, O.B.E., 392 Duke St

Ex-Bailie Roderick Scott, Meat Market.

John F. Munro, 133 Comelypark Street

Samuel L. Neill, 120 Duke Street

W. D. Newton 5 Moss Street

Ex-Bailie William Nicol, 305 Golfhill Drive

William Nicol, Jun., 557 Alexandra Parade

Dr P. J. O’Hare, Highfiield, Broompark Circus.

Parish Councillor James Paxton, 255 Golfhill Drive

Parish Councillor Hugh Smith, 179 Reidvale Street

John Stuart, 165 Bellflield Street

William Taylor, L.D.S., 9 Oakley Terrace. Thomas Gibson, 78 Roslea Drive

Jas. J. McIntosh, 104 Armadale Street

Parish Councillor J. Marshall Brown, 323

Craigpark Drive.

Mrs Agnes Lauder, 34 Aberdour Street

MINISTERS OF DENNISTOUN CHURCHES

Bluevale Parish Church—Rev. J. A. Boag, M.A., 645 Alexandra Parade

White-vale U.F. Church—Rev. Wm. Barclay, M.A., 6 Lloyd Street,

Sydney Place U.F. Church—Rev. David Forfar, M.A., 21 Broompark Drive

Whitehill U.F. Church—Rev. J. Stewart Lawson, 22 Circus Drive

Blackfriars Parish Church—Rev. D. F. Liddle, B.D., 11 Westercraigs

Rutherford U.F. Church—Rev. James McLeod

Wellpark U.F. Church—Rev. Hugh Mair, Brooklyn, Circus Drive

Dennistoun Established Church—Rev. R. Walker Muir, 295 Golfhill Drive.

Dennistoun E.U. Congregational Church-Rev. John Murphy, B.D

Regent Place U.F. Church — Rev. J.McCallum Robertson, M.A., 40 Circus Drive

Alexandra Parade Primitive Methodist Church—Rev. R. Robertson, 141 Onslow Drive

Dennistoun Baptist Church—Rev. W. H. Shipley