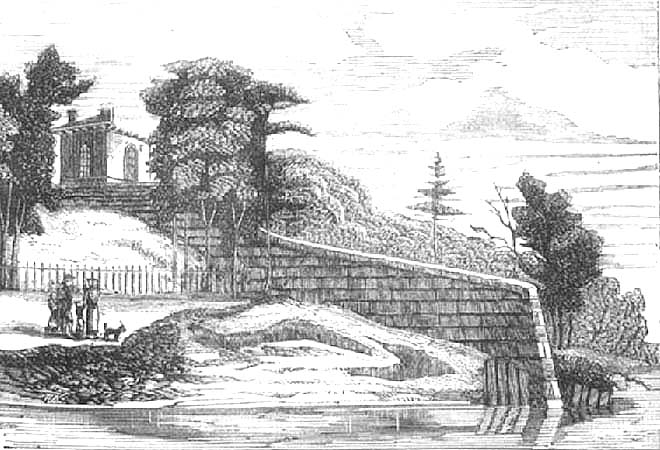

Thomas “Lang Tam” Harvey was a whisky distiller who lived at Westthorn on the outskirts of Parkhead. His grounds went down the bank of the Clyde and, in order to protect his privacy from people walking on the popular Clydeside footpath, he built walls at either end of his property to close off a one mile section to the public. In 1822 an angry mob principally composed of weavers and other operatives from Bridgeton and Parkhead, armed with piekaxes and crow-bars, laid siege to the obnoxious barrier tore down one wall and were pulling down the other when the Enniskillen Dragoons arrived to quell the  disturbance. Several people were thrown in jail and Harvey began rebuilding his dyke.Harvey’s determination to block the Clydeside footpath was challenged in the courts by a group of men from Glasgow and from Tollcross, Parkhead and other villages to the east of the city. The charges against the wall-demolishers were quashed in the House of Lords after an appeal, and in 1826 Harvey was ordered by the Court of Session not to rebuild the dyke.

disturbance. Several people were thrown in jail and Harvey began rebuilding his dyke.Harvey’s determination to block the Clydeside footpath was challenged in the courts by a group of men from Glasgow and from Tollcross, Parkhead and other villages to the east of the city. The charges against the wall-demolishers were quashed in the House of Lords after an appeal, and in 1826 Harvey was ordered by the Court of Session not to rebuild the dyke.

A medal was struck with the inscription: “The Reward of Public Spirit.-The Citizens of Glasgow to Adam Ferrie, George Rogers, James Duncan, John Watson, Junior, John Whitehead, for Successfully Defending Their Right to a Path on the Banks of the Clyde, 1829

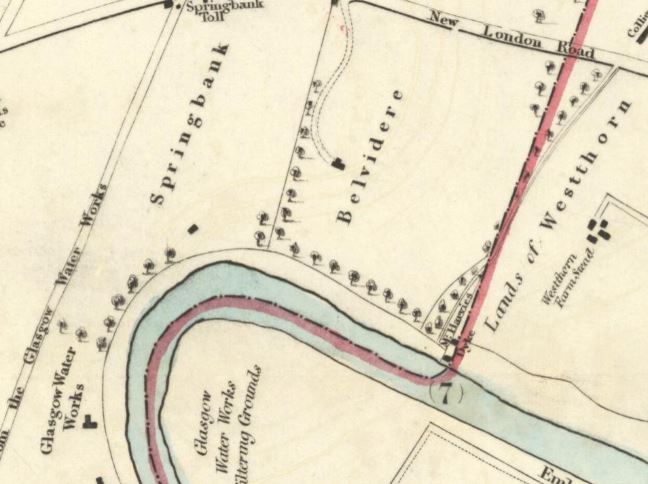

Map of where Mr Harvies Dyke would have been

Heres an extract from Charles MacEwins book The Old Historic Church Of Tollcross And Tollcross District

A cause celebre which, some two or three generations ago set the whole of East Glasgow by the ears, was the law plea known as the “Harvey-Dyke” case. Thomas Harvey, or “lang Tam Harvey,” as he was commonly called, began the world as a carter at Port-Dundas. Thinking not without cause that a “change-house” would serve his ambition, which was of the “o’er-vaulting” order, much more readily than the loading of waggons and driving of teams, he gave up the carting and took to whisky selling. Soon Harvey’s change-houses or “divans,” as they were called appeared all over the city and became celebrated as first-rate in style and order. He quickly grew rich and bought Port-Dundas distillery for £20,000.

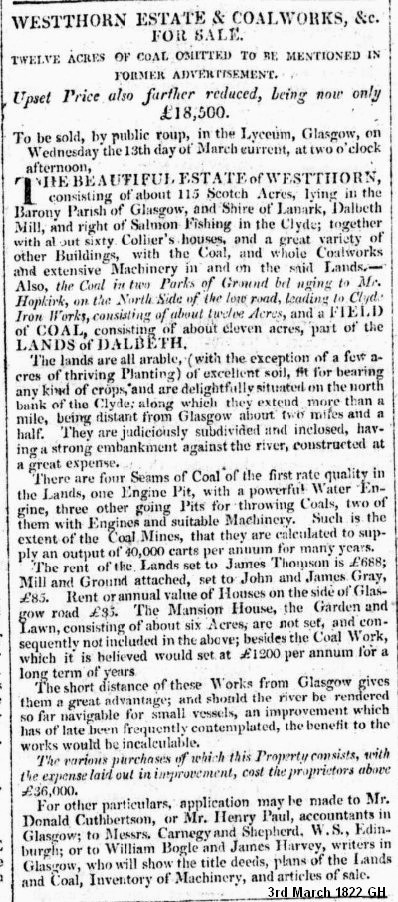

The ambition of Harvey expanded with his fortune, which was only in keeping, as he imagined, with his personal appearance, he being large and muscular, with short hair and red whiskers. He bought Westhorn in 1821, and furnished the mansion-house at a cost of £10,000, although he was a bachelor. He died poorer than when he began life, and is said to have ended as an actual pauper.

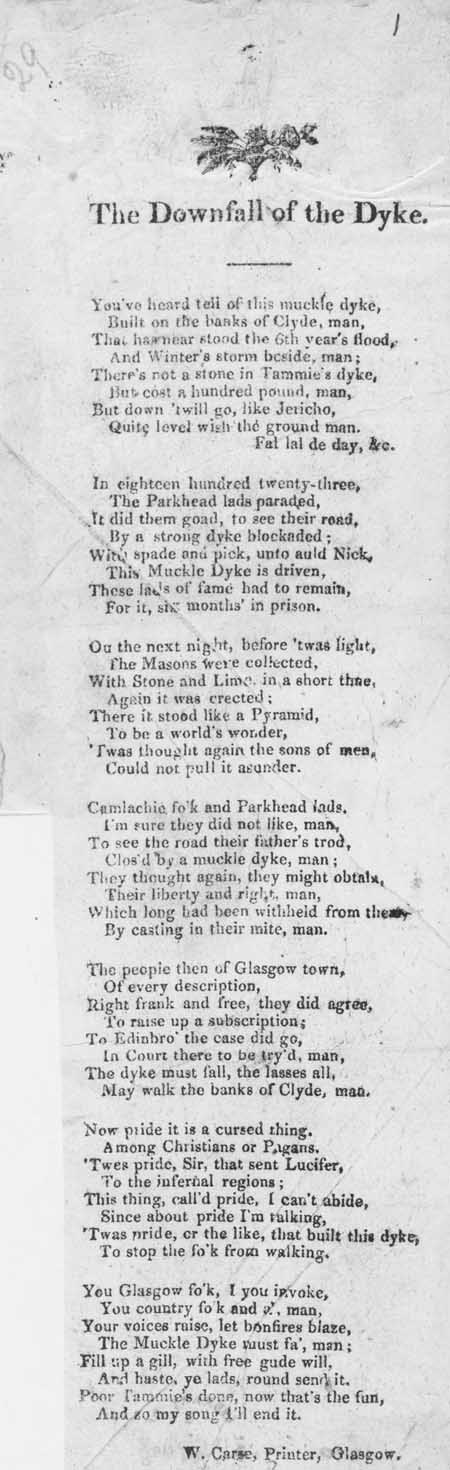

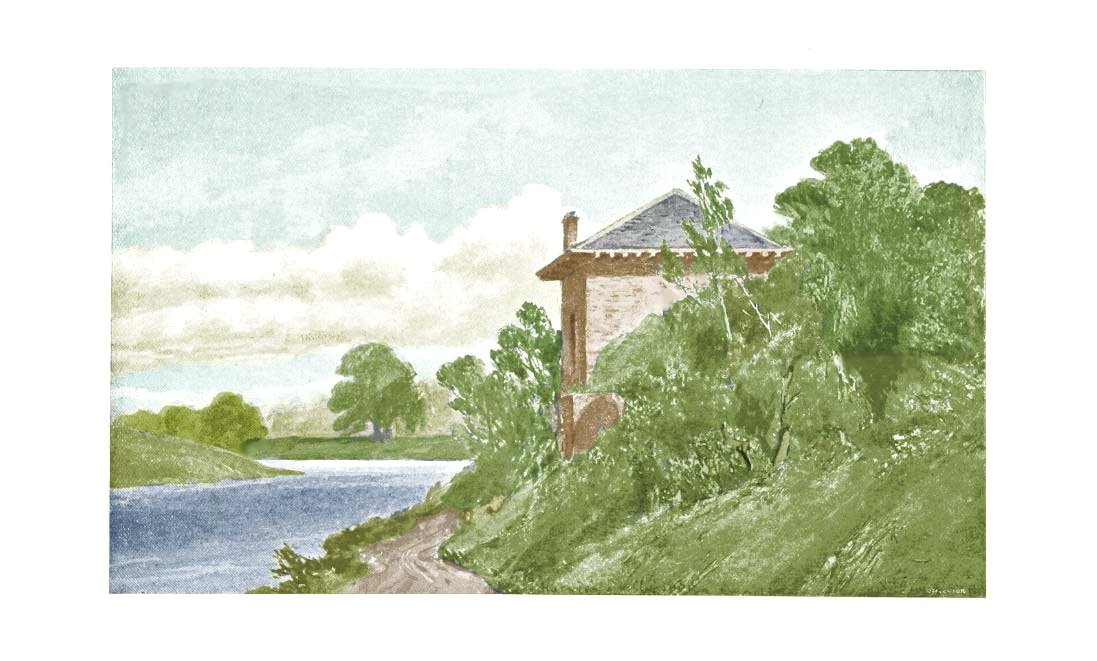

A public footpath ran along the northern bank of Clyde from the city to Carmyle—a distance of about five miles. Harvey to preserve the amenity of his property erected (1822) a thick stone wall on the west across this public footpath, which he carried down into the river and armed all along its extent with stout iron pikes. This wall the people demolished as an interference with their ancient and undoubted rights and liberties. Harvey rebuilt the wall, and the people again destroyed it.

On the second occasion (21st June, 1823) the destroyers were surprised about the time their work was finished by a detachment of dragoons. Some of the people were taken on the spot, some were arrested on the roads, forty-three in all, and a lad received a cut from a sabre in the arm. The throngs were tremendous. The whole of the highway between Tollcross and Camlachie was alive with people during the entire night—friends were anxious for their relatives, and the curious had itching ears.

James Duncan was a bookseller in Glasgow and also a landed proprietor. He organised the public opposition to the high-handedness of Harvey. Alexander Rodger, the Bridgeton poet, fanned the popular fury. Along with them a committee, amongst whom appear the names of George Rodger of Barrowfield Printworks, John Kinniburgh, feuar, Tollcross, James Reid, feuar, Parkhead, and Alexander Brechin, feuar, Carmyle, resolved to carry the matter to the Court of Session. Subscription sheets were heartily and extensively signed in Tollcross, Parkhead, Bridgeton, and elsewhere. James Bogle, writer in Glasgow, Colin Dunlop, member of the Faculty of Advocates, and Mr. McNair of Greenfield, gave evidence in favour of the contention of the people. The public were successful, but Harvey was not satisfied, and carried the case to the House of Lords, which finally (July, 1828) set the matter at rest by unanimously affirming the judgment of the Court of Session. As an example of the extraordinary interest and excitement which this famous law suit evoked in the district, it is recorded that when the witnesses on behalf of the community, many of whom were old men, were informed that the case had been gained, some of them burst into tears of joy, saying that they would have run any risk— it was a period when, owing to the extreme cold, travelling for aged people involved no little danger to health— in order to get back their favourite walk.

Advert from 1822 The Glasgow Herald