Captain Julius Morris Green was captured by Nazis in 1940 at Dunkirk

He spent most of the war in POW camps including Colditz castle

MI9 recruited him as a spy and he sent information back in coded letters

Certain codewords positioned at specific points on the page could be translated by agents back in London using a grid system

Green sent messages from various prison camps from 1941 until 1944

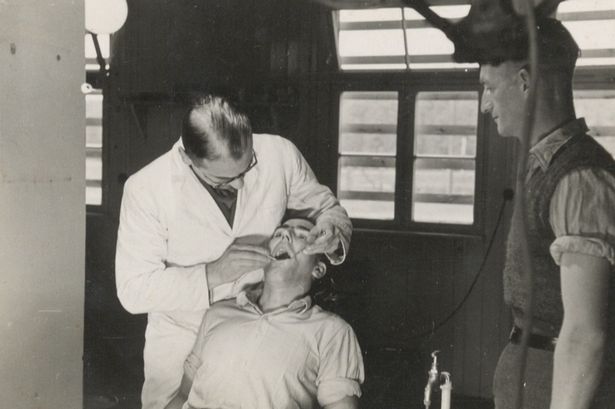

Before the outbreak of the Second World War, Julius Morris Green was nothing more than a dentist, practicing his trade in a small surgery in Glasgow.

But after being captured by the Nazis at Dunkirk in 1940 he became a spy, risking life and limb to send coded messages on the German war machine back to the intelligence services in London.

Writing from the infamous Colditz castle near Leipzig from 1941 to 1944, he sent letters to his family on seemingly innocent subjects, such as his infatuation with a made-up girlfriend called Phillipa.

ut by only looking at the fifth and sixth words on the first few lines of each letter, spies at MI9 were able to decipher messages hidden within the notes.

To anyone who spoke English, the letters would have seemed odd and disjointed, but as German censors often only had a rudimentary grasp of the language, they were able to slip by unnoticed.

In one coded letter from November 1943, Green writes to his father: ‘Phillipa appears quite the most winsome lass, but don’t get frightened, she’s not my type! I think that I’m a great deal too slow for her & anyway, I could never marry a girl whose idea of enjoyment is to dance until 3am every night.’

The whole letter when decoded reads: ‘Making diesel only petrol a failure.’

MI9 was an intelligence branch whose job was to communicate with and aid resistance fighters, to try and rescue soldiers trapped behind enemy lines, and to establish links with British POWs to send them advice and equipment.

As a dentist, Green was asked to treat other prisoners and the German troops stationed in the camps, and used this opportunity to pick up information.

He also visited other prisons to treat patients, and so was able to pick up on conditions in each.

He would then send information on what was happening at the camps, strategic details about German shipping and troop movements, and lists of useful materials for potential escapes.

A collection of 40 coded letters sent between Green and his family living in Scotland will be sold at Bonhams in Knightsbridge on June 18. They are expected to fetch between £4,000 to £6,000.

Notes on the auction items say the letters sometimes ‘read like a caricature of a faulty language manual’, but were just clever enough to slip past the German censors who read each letter.

Simon Roberts, a specialist in the book department at Bonhams, said: ‘Museums and libraries ought to be interested in these items, they highlight an important part of what was going on in World War Two.

‘But recently the war is a subject that increases appeal to the private collector.

‘This is quite an unusual collection. It is being sold in a lot of letters including some from (US President) Eisenhower.

‘We sell much more from World War One, which have proved popular in the past few years leading up to the centenary this year, however the anniversary of the D-Day is coming up.

‘The fact these are coded letters adds a fun element. Whoever buys them could spend many days decoding them all and having fun with them.’

Captain Green, a Jew born in 1912 in Killarney, County Kerry, graduated from the Dental School of the Royal College of Surgeons in Edinburgh and practised in Glasgow before the war.

He joined the Territorial Army in 1939 and was posted to the 152 (H) Field Ambulance of the 51 Highland Division.

He was captured with his brigade at St Valery in northern France during the retreat to Dunkirk in June 1940 and spent the remainder of the war in several camps including Blechhammer, Lamsdorf, Sandbostel, Westertimke and Heyderbreck.

The spokesman added: ‘The letters sometimes read like a caricature of a faulty language manual, and had the German censors employed someone with a native command of English they would have immediately spotted that something untoward was going on, a fact of which Green himself was all too aware.

‘The risks he was running, as a Jewish prisoner-of-war in Nazi hands, hardly bear thinking about. Under the surreal humour of his letters lies horror and quite extraordinary bravery.’

After the war his papers were presented to the Imperial War Museum in London.

The collection includes snapshots taken in the camp of Green undertaking dentistry examinations and fellow prisoners, a watercolour portrait of Green as a POW, a Christmas postcard from Laufen Castle in 1940, and caricatures of Green and some of his friends.

He later wrote a bestselling book about his experiences entitled From Colditz in Code.

He also worked as a businessman for a number of years before returning to dentistry. He died in September 1990.

Story taken from Daily Mail