In 1920 Ex Baillie David Willox wrote a book called Reminiscences of Parkhead that was his memories of the shops, public houses, and the people of Parkhead. Parkhead History would like to hear your memories of Parkhead. The games you played, school days, work and the church you attended, just e mail us at info@parkheadhistory.com or get in touch through the contact button.

—————————————————————————————————————————————————–

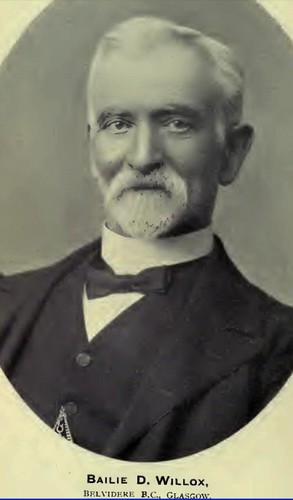

Willox

At the oft repeated request of my dear son Charles, presently residing in America, I set myself to write down a few of my recollections of the past in connection with our family. These must necessarily have little interest for the ordinary outsider but to one of the family they may interest if they do not instruct.

Who has not felt the desire to know something of their forebears either male or female, even in the humblest walks of life and especially after the careless and sportive days of youth and early manhood passed away?

Speaking for myself, I must admit that in my early years I was so taken up with passing events of boyhood that I had no thought, or at least very little, of prying into the past, my young thoughts being mostly taken up with the amusements of the passing hour and dreams of the future.

In writing these Reminiscences, it occurs to me that I cannot do better than write them out under the following headings, the Place, the People and the Pastimes of Parkhead, commencing as far back as I can remember, say about 1850. I would then be about 5 years of age, having been born on 3 June 1845.

The Place

Parkhead was then in 1845 a small weaving village in the east of Glasgow, about two miles from the Glasgow Cross. It consisted of one main street running east and west, called Great Eastern Road and another called Westmuir Street, running due east from the Sheddons (Parkhead Cross) with other streets converging on the Sheddons (cross) such as, Dalmarnock Street, Burgher Street, New Road now Duke Street, west from the Sheddons, we come to Elba Lane, Reids Lane and Stewarts Lane, on the Southside and Burn Road on to the Northside at what we call the west end. The houses in this direction, especially on the south were mostly one storey on the north they were mostly two storey, many of them thatched and some tiled with red course tiles but these coverings for the houses have now almost totally disappeared and have given place to the more modern and artistic slate covering.

There were few shops for the sale of goods in this small stretch of the Great Eastern Road which we may call the west end and they were of the most unpretentious character. Window dressing had not in those days attained the excellence it now has when it may be considered one of the fine Arts. You might come across a bit small window packed with an indescribable assortment of miscellaneous articles without regard to either time or place, mostly appealing to the juvenile fancy for purchasers, such as, half-penny keek shows, marbles (bools), of various colours, Tops, Peeries, false faces, and valentines. ‘Old Brody’s’ was perhaps about the only shop that made any pretence to supplying the general wants of the community. It stood almost on the identical site of the Clydesdale Bank of the present day, facing the top of Dalmarnock Street (Springfield Road). This with the exception of two or three bits of small green groceries was about all the facilities there were for purchasing the necessaries of life, while in the same stretch there were four pubs on the opposite side. All I remember were another pub and a butcher shop. The rest were hand loom weaving shops.

Dalmarnock Street runs south from the Great Eastern Road it was anciently called dry thrapple, but why it was so called I cannot tell. Even in my early days it hardly ever got any other name than dry thrapple, especially among the older people. It consisted then principally of one story houses, mostly of one room and kitchen, entering off the same close as a four loom shop. Some four loom shops had the house above, which were attics, some which still remain. On the west side of the street was a wide and deep goat or ditch, with a fairly high hedge, beyond which were little patches of garden ground, then the houses and larger garden spaces behind. At the top nor-west corner was a large open space called Gib’s yard, usually containing a large stock of timber, among which we youngsters used to play at some little risk of getting injured, and not infrequently of being chased. Off this street, near the site of the palatial Newlands school, was one of the finest wells in the whole neighbourhood called ‘Carrick’s Well’. The water was good and plentiful, even in times of extreme drought, but my impression is that it was a private well, and was situated in one of the gardens, outsiders probably having to pay a small sum for a supply. I have been told that in later years when digging for the foundation of the Newlands School the workmen struck the source of this well, and it was only after great trouble and considerable cost they overcame the difficulty of stemming the flow of water into the foundation. The last houses on this side of the road going south were three or four neat little cottages and beyond that a fairly large sized park, where in later years I used to herd. On the other side of the street, the east, there was nothing remarkable apart from a number of weaving shops, and an opening or lane called ‘The Stiles’ a nice little rural pathway that led into Burgher Street. This has been swallowed up in the present Dechmont Street, and large four storey tenements, which are continued down the east side of Dalmarnock Street to the Caledonian Railway round and along Thomson Drive (Whitby Street) to the Coach Road (Helenvale Street).

Let us pass through ‘The Stiles’ as it was then, with its beautiful hawthorn hedge on either side, into Burgher Street, which is closely associated with our (Willox’s) family history. A considerable portion of this street was an then an open green at the south end, with a few one storey weavers’ shops and dwellings on the west side. But the first house on the opposite side was rather pretentious for those days, consisting of one block with two dwellings of room and kitchen, each with a mid-room and one house had a four loom shop beneath, and the other had a six loom shop.

I have never clearly understood whether the whole of the whole block belonged to our ancestor ‘William Willox’, or only that portion inhabited by him, namely the room and kitchen and mid-room, with the six loom shop beneath. I am strongly inclined to believe that the whole block was built by and originally belonged to him, as he seems to have been a man of some standing and character in the district. But more of him by-and-by, when I come to deal with the people. It was in the mid-room that my grandfather and grandmother took up house when they married. Both grandparents were Willox’s, and were cousins. My grandmother’s full name was Jeanie McGregor Wardrop Willox, which is somewhat significant of other connections. No wonder my fancy clings round Burgher Street. I myself was born between Burgher Street and Dalmarnock Street in a place called ‘Nae Place’. When married first I took up house in Burgher Street and Jeanie, my daughter was born there.

I have now for some years owned a little property at 48 Burgher Street. But I haven’t finished with the street yet. Immediately joining our old man’s house were two or three red tiled houses, and what is now called McEwan Street, in those days, was called ‘Juck Street’. It was entirely occupied by weavers, mostly all four loom shops, with dwellings above.

The opposite south side of the street was unbuilt upon, and made an ideal playground for the young weavers. With the whole open country for many miles east and south before them, it ran and runs yet, from Burgher Street to Helenvale Street, there is little to note. On the right we come to the ‘Big Land’, three or four stories high (still standing) with weaving shops below, then the Smithy owned by ‘Big Tam Strachan’, and then the pawn building, with a joiner’s shop at the corner. At the opposite or west corner stood a decent two storey building, occupied by Dr. Wm. Young, the only doctor we had in the place in those days. What a glorious time the old women must have had then compounding drugs and bringing hame weans. The doctor’s house and the adjoining buildings right west to Dalmarnock Street all disappeared to make room for the Savings Bank Building and the adjoining four storey tenements.

We will now pass along Duke Street going north and starting from the Cross (Sheddens). Duke Street was then called New Road. The first and almost only building of any note then was the ‘Gushethouse’, owned and occupied as a licensed place by George (Geordie) Honeyman, who had the reputation of dabbling in more things than whisky. He was, besides being a liquor merchant, a water merchant as well, and sent carts through the vilaage with large water butts, retailing the precious article at so much a ‘stoup’. There were a few one storey houses extending from his premises down the street in one of which a maiden lady named Agnes Paterson kept a grocer’s shop. She did an extraordinary amount of business for such a small place, probably because she gave ‘tick’ (trust). Her shop was a favourite one of the Forge’s labourers. I believe her trust was often misplaced, and she met with many losses and disappointments.

There were no other buildings on this side of the street, and a low broken stone wall or dyke ran most of the way down to the old Forge gate at the junction of the back road.

Coming back on the east side there were two or three 2 storey buildings, one of which was a school called ‘Corkey’s School’, from the fact that the Schoolmaster, Mr. McAuley, was said to have a cork leg. he was said to be a splendid teacher, but rather severe as a disciplinarian. I was not long under him. One could not get learning for nothing in those days any more than you can now. The corner building right opposite Honeyman’s, where we started from was a white-washed one, two stories in height, I think part of which was occupied by Jock Arbuckle as a barber’s shop. Mrs. Arbuckle on busy occasions did the ‘soaping’ and Jock did the shaving. I used to get my hair cut there, the charges were a halfpenny for shaving and one penny for haircutting. There was no picture house in those days in the New Road, nor was there a public hall.

We will now take a turn down Westmuir Street, and note some of the changes that have taken place there. This large and beautiful range of four storey tenements, commencing on the corner of Duke Street, was built by Messrs Watson, an old Parkhead family, and took the place of some old buildings, such as I have already described. This building at the corner of Gray’s lane or Gray Street (Dervaig Street), you will notice is only two stories high, and is presently occupied by the Watsons themselves, as a licensed grocery business. In my youg days it was but a very small concern, kept by the present Watson’s father ‘Rab Watson’. I cannot say positively if it was licensed then, but I think it was. Old Watson sold all kinds of grocery goods, and in addition grain and feeding stuffs for horse and cattle. He must have done fairly well, for besides leaving them a good business, which under the able managementof the younger Watsons, has developed into its present gigantic proportions, with, I have heard it said, a turnover of not less than £600 per week.

The top flat presently occupied by the Watsons was once a school room, under the management of a Mr Malloch. This school by-and-by was removed into larger premises, and found accommodation for the use of the tawse in a little hall adjoining the Watson’s premises in Gray Street. Mr Malloch having occupied the ministry, the school was ruled over by James Jarvie. But James, I think must have been fond of the ‘maut’ (malt), as he didn’t retain his position long, and drifted back to the loom.

Gray’s Lane in those days ran, and runs still from Westmuir Street down to what is now called East Wellington Street, on the north side of which, nearly opposite the foot of Gray’s Lane, stood the old ‘Waster’ coal pit, a pit of considerbale antiquity even in those days. It was said the coal used to be brought to the surface in baskets by hand, and the workings were said to extend underneath as far west as the cross of Glasgow. I remember the pit working, but my earliest recollections of it, the method of raising the coal was mechanical, and by direct lift, not by hand in baskets, and though it was said women used to work there, I never happened to see any.

Returning to the top of Gray Street at its junction with Westmuir Street, we bend our steps eastward. From the corner, for a considerable way down Westmuir Street on either side, were a number of weaving shops. Those on the south side were mostly two stories of the usual type, the shops below and the dwellings above, with two or three going closes, which led into ‘Steen’s Court’, a triangular space that lay between Westmuir Street and Great Eastern Road. There were two or three closes on this side of the Court, and a Court entrance into it as well as on the south side. These through closes offered fine facilities to us youngsters in our games of hide and seek, hurly burly, smuggle the geg, etc. etc.

On the north side from Gray’s Lane right down to Ravel Raw (Row), were a series of one storey houses, with one two storey one about half way between the two places named. This was occupied by Jack Marshall. The low buildings, which I presume had originally been weaving shops, were occupied by James Waddell, as a Comb work, which was then, I think, the only place of public employment in Parkhead, except the Forge, which was then a very small concern compared with what it is now, in these days of hundred ton guns, armour plates and mighty shafts and throw cranks.

The Ravel Row ran, as it still does, north to its junction with East Wellington Street, and nearly opposite Ravel Row, on the south side of Westmuir Street, stood the Old School Pit, bounded by Pump Riggs, now Sorbie Street, then a narrow hedge lined pathway running between Great Eastern Road and Westmuir Street. The Old School Pit is one of my earliest recollections, with its stone built engine house, and its massive cast iron beam protruding, working up and down loke some gigantic pendulum moving the wrong way. From this point down Westmuir Street, there was little of interest to anyone. A series of low one story buildings on either side. The first opening on the left hand now called Nisbet Street, was then simply an open space, then some low one story houses where the present Parkhead School stands, and adjoining the Back causeway, which led down to the ‘Black Engine Pits’ two in number, and quite near to each other. These Pits were situated just where Beardmore’s large engineering (G) shop is built, and gave employment to quite a number of colliers, for whose accommodation a long row of one story houses was built, running east and west. This was called ‘Colliers’ Raw’ (Row) and was occupied by quite a colony of relations, mostly Haddows, Baxters, Tennants, Winnings etc., some of whose descendents still live in the neighbourhood. Woe betide the luckless wight who fell foul of any one of them. The whole clan were in arms at once.

The next opening is Winning’s Row, and opposite on the south side of Westmuir Street stood the old gaol. Why it was so called I cannot tell, unless it was from its dull and dismal appearance and its foreboding outline. The houses were very small, and had the name of being very unhealthy. Quite a little den of people lived here notwithstanding, and they were nearly all swept away during one of the visitations of cholera. We youngsters had always a sort of passing fear on passing the dismal looking den. it has long since disappeared, all but one of the Gables, which still stands, and forms the boundasy line of my own property in Westmuir Street. We have now reached the entrance to the Quarry.

In my early years it gave employment to quite a number of men, and it was here the soldiers from the barracks used to practice ball firing at cloth targets. It was quite an event in our young lives gathering the lead after the soldiers left. The quarry was also a great source of supply to the boys of clay for making crackers, which formed like the shell of a pennypiece, and gave a fairly good report when thrown upon the pavement with the opening downwards. There were two or three deep and treacherous holes here, where we used to sail rafts made of two or more pieces of wood with a cross piece or two. This was a highly dangerous pastime, and occasionally lives were lost, but what dangers will not the young adventurer.

East of the quarry stood the Caroline Pit, perhaps the most important in the whole district, where engines, in addition to raising great quantities of coal and other material, had to pump an immense amount of water out of the underground workings. Here on the burning ash-heaps we used to roast potatoes, and oh! what a palatable morsel they were.

We will now retrace our steps, and, starting from the usual point (the Sheddens) take a stroll east along Great Eastern Road in the Tollcross direction, and note some of the changes that have taken place there within the last seventy years.

The large four story building that forms the gushet house has taken place of a two story one that stood there, the under flat of which was occupied by Gib (Gilbert Watson) as a baker’s shop and dwelling house, with the top flat occupied as a dwelling house and post office. The entrance to this was by an outside stair, rising from Great Eastern Road, with the bakehouse adjoining, a low one story building, then a cart entrance leading into Steen’s Court, now altogether done away with.

On the opposite side of at the corner of Burgher Street stood a two story building, the ground flat occupied as a cartwright’s shop, and the top as a pawnshop, the latter owned by Charles Gallacher, a typical irishman, ready and witty. On either side the few buildings there, were of the two story class, weaving shops on the ground floor, and dwellings above, the latter of the one room and kitchen class. These extended almost to the Coach Road (Helenvale Street), with one 1 story house, where the plasterers’ yard now is. The houses on the north side of Great Eastern Road were of the same class as those opposite along to Montgomerie’s Opening, opposite the Coach Road. This opening which led to the Bowling Green, the old Parkhead Bowling Green, one of the oldest in Glasgow, was familiarly known as the ‘Old Bog Hole’. It was on that green that I first saw the game of bowls. Little did I think with childish interest, that I myself would yet become an enthusiast of the game. It was a break away from the old club that formed Belvidere Bowling Club, with their green down Elba Lane, on ground now occupied by Barr’s Lemonade Works. The same opening gave entrance to a bakehouse. Halfway between the Sheddens and Montgomerie’s Opening was the beaming room where the weavers had their webs beamed. This was a process of winding the web as it came from the warpers on to beams or rollers approximately to the width of the cloth when woven. The beaming room was on the top (second) flat, and adjoining on the same stairhead was alittle hall or room where public meetings were held, the only place of public meeting then in the village apart from the school room. This was quite an important centre in those days, and although it was ony 30′ or 40′ long by about 15′ wide, it met nearly all the local requirements of the place and was fairly well taken advantage of.

Montgomerie’s house was a licensed place of call, and was much frequented by carriers. It is still a licensed place, presently occupied by Samuel Hay Gardner. At one time there was a little hall, or rather a large room attached, where dances were held, and was much patronised.

On the opposite side of the road froming the corner of Helenvale Street stood Brown’s land, a dull uninviting two story building, consisting of weaving shops and dwelling houses, with a large arched pend leadinginto a small court with three or four outside stairs leading to the houses above. The Public Library and Washhouse now cover the place. We may as well dsipose of Helenvale Street while we are here. There was then little to arrest the attention, old Hay’s Farmhouse and Steading, with byre and barns adjoining Brown’s Land, which still stand as a momento to former times. A little further south stood McEwan’s Cottage, with a little flower plot in front, railed in. The railing and plot were in after years removed, and the cottage still stands naked in front, with an oil work adjoining the north.

We now come back to ‘Juck Street’, now called McEwan Street, already referred to, and going south enter the Coach Road leading to London Road. The Coach Road then was a beautiful carriage way between two nice hedges with fields on either side, and was originally, I believe, the main access to Belvidere big House. This stood in its own grounds, which with other buildings now form the well known Belvidere Hospital.

We will now return to Great Eastern Road, and passing eastward, we come to a long row of one story houses with attics above. These were mostly all of the weaver’s class of shop, and were known by the name of ‘Shinty Ha’, dear old ‘Shinty Ha’, every foor of which is hallowed ground to me, as the best known of my boyhood playgrounds. The houses stand on the south side of Great Eastern Road, at a considerably higher level than the causey, fronted by a dyke with openings and steps opposite every door. The dyke was a favourite source of amusement. It rose some two or three feet above the building level of the houses, and we boys used to take great pride in being able to run along the top, leaping across the stairways, and sometimes leaping from the building line right over the wall to the causeway on the other side, which was considered by us no mean deed of daring.

On the other side was a long row of two story houses, all weaving shops below, with one outside stair entering from the back. In the front street there was one outside stair. This rwo ran along until its junction with Sorbie Street (the Pump Rigg) and has undergone little alteration to the present day (1920), except that the weavers have all disappeared. A public house stood at the corner, there is still a licensed house there yet, but it is not used as a place for sitting down now. It was then occupied by Alexander Farmer, a blacksmith to trade. He was son-in-law to George Honeyman, already referred to, and was said to have killed a man at one time in a quarrel, and while in a fit of passion. Farmer’s public house was really the last house on that side of the road between Parkhead and Tollcross, ecept the U.P. Manse, which stood a little off the road opposite the Ree. The Manse still stands, broken up into small dwellings, the entrance to which is off Crail Street. There was no Crail Street in those days, all beyond were fields and hedges on this side of the road as far as Mackinfauld Road, beyond which I do not intend to take you at present.

We will, therefore, return to ‘Shinty Ha’, known sometimes as the high dyke. There were quite a number of characters lived in ‘Shinty Ha’ in those days, some of whom I have occasion to note when I come to deal with real people. At the end of the row there was an opening into the fields called Duff’s Opening, then another house or two. These and the row itself have undergone external alteration, and present the same outline to the eye today as they did when I was a boy.

We are now in the neighbourhood of the Hay Loft, but before proceeding farther, let us glance at the other side of the road. A hedge ran all the way fown there, lining the street, and was supposed to fence in Hamilton’s Park, so called from the farmer who created it. The Parkhead Junior Football Filed now covers the greater part of it. It used to be a favourite resort for us, even though it was prohibited, for chasing bumbees and butterflies, and occasionally a game of rounders.

The Hay Loft was simply a small cluster of weavers’ shops and dwelling houses, but the little one story house to the east and facing Great Eastern Road, was of different character. That was the ‘White House Inn’, and was occupied by Alexander Anderson. He seemed to do good business, and his place was the last place of call between here and and Tollcross for the carters and carriers going east. A terrible tragedy was enacted here, which afterwards overshadowed the place with a gloom that never lifted, and it gradually went from bad to worse until at last its roofless walls were all that remained of the ‘White Horse Inn’. The tragedy was the murder of Mrs. Anderson by her husband in a fit of drunken passion. I remember the first intimation of it I had while playing at Granny McPhee’s fireside. A neighbour woman came rushing in, exclaiming ‘uh! Bell, Bell, Sandy Anderson has killed his wife.’ I was a small boy at the time, and the alarming intelligence thus announced, had not the same import to me as it might have to older minds, but the cry of that woman occured to my memory, and is likely to remain with me as long as I live.

The Inn derived its name from the signboard above the door, which bore the representation of a white horse painted on a large board, supported by tall wooden beams, one on either side of the door. I was too young to be interested in the after fate of Anderson, but it is my impression that he got fifteen years transportation. A large crowd turned out for the funeral of Mrs. Anderson, I remember seeing it. She seems to have been highly respected by neighbours, and bore an excellent character among them for thrift and well-doing.

It was in a shed or old stables at the Hay Loft that the wonders of the magic lantern were first revealed to me. Someone kindly disposed towards the young gave an entertainment of this kind, and I was there. What a treat; never had my young eyes beheld such wonders, and the rapture of that hour were with me for long afterwards.

We have now reached the neighbourhood of the ‘Ree’ the last place I intend to deal with in these rambling notes. The principal portion of the Ree consisted of one story houses, with a back land at the south east end, and one or two detached buildings of similar character. They had probably been collier rows at an earlier period, and consisted of a ‘but and ben’, all earthen floors, reeking with damp, and they must have been very unhealthy.

At the time I write of, these houses were exclusively occupied by weavers and their families, the one apartment serving as ther living room, where eating, sleeping and all other domestic concerns were carried on. The other served as a workshop for two looms, with a small bed, in some instances, squeezed into a corner. How it was possible for people to live under such conditions is a mystery to me now, but the houses were all inhabited, and there was seldom one to let.

At the south east side of the ‘Ree’ was the Ree Road, a passage between two hedges, running south towards the London Road. This seemed originally to have been a cart or carriage way, and was a favourite place of recreation. It made a fine walk for the weavers in their intervals of their labours. At the east end were a few weavers shops and dwellings, and behind these was one of the best draw wells to be found in the while district. It was fairly deep, and required a pretty long rope to reach the water, which was clear, cool and plentiful, even in the hottest weather.

I have now reached the end of my notes on the place, and will have something to say of the people.

The People of Parkhead

You will have gathered from the foregoing that the inhabitants of Parkhead in those days were principally of the weaving class, and there were quite a number of highly respectable families among them. Among the oldest, if not the very oldest of them, was our own family, and as that is the main object of your interest, I shall try and tell you all I know of them. Much of what I may be able to tell you only came to me in a fragmentary manner, and is only of a traditionary character.

There seems to have been two branches of the Willox family, the one represented by the old William Willox of Burgher Street, my father’s grandfather on his mother’s side, and Sergeant David Willox, my father’s grandfather on his father’s side, so that my grandparents were cousins, my grandmother being the daughter of William, and my grandfather the son of David. So far as I know, William Willox’s family consisted of 3 or 4 daughters and one son. These were Jeanie, my grandmother, Elizabeth; I don’t know the names of the other daughters, Alexander, (Swift), and he (the old man) seems to have been a widower for some years. Before his death the family were all brought up to the weaving trade, under the old man’s care, and it seems to have been a fairly bien house, the old man himself being well to do, and having excellent character. Indeed he seems to have been a sort of aristocrat among his class, and as I have been told, was one of four who had a Parliamentary vote in the village, the then whole voting power of the district. Think of it now, with its many thousand voters. I understand it was quite an event when the old man went to vote. The candidate’s carriage drove up to the close mouth, and a crowd would gather round to see him driven off. It must have been interesting to see the old gentleman step into the carriage, with blue swallow tailed coat, his knee breeches, and silver buckles on his shoes. This is no figure of imagination; I have heard it hundreds of times, both inside and outside of our own family.

Jeanie married my grandfather, Elizabeth married on William Archer, and one of the other daughters married one of the name of Miller, the other I cannot tell you anything about. Alexander married a girl called White. He had only one son called William, of whom I lost trace. He went to the north of Ireland, somewhere about Newtonards. I cannot tell you anything of my grandmother, Jeanie, as she died long before I was born. Elizabeth (Leezie) whom I knew well, was a bit of a character, and was quite an interesting figure in Parkhead, a tall, muscular woman, as I remember her, thin and wiry, and active to her end. Everybody knew Leezie Willox, and some of the smart ones who thought to take a rise out of her were often overwhelmed by her ready wit and caustic replies. Poor soul, she had a lifelong struggle with poverty and hardship. I need not mince matters; her husband was one of the laziest men I ever knew. He did most of the planning for the household, and Leezie did all the prouching (foraging) or in other words, he made the balls and she fired them.

Alexander as he grew up seems to have fallen into evil habits; probably more so after the old man’s death, spells of drinking and idleness are not conducive to success in life. Drink seems to have been our family’s curse, though we may show many instances of sterling worth, strict integrity, sobriety and well being. Even before the old man’s death, things seem to have been going backwards with him. His family were growing up, and less amenable to parental control, while the domestic expenditure increased, so much so that he was forced to borrow money on security of the title deeds of his property, receiving a back letter from the lender acknowledging the temporary character of the loan. In one of Alexander’s drinking bouts, he handed this back letter to the lender for £5, thereby robbing his old father, and selling his own birthright for worse than a mess of pottage. This is how the property in Burgher Street was lost to the family, and occasioned Leezie a world of trouble in trying to recover it, even through the assistance of the Parochial Board.

Jeanie, my grandmother was a daughter of old William Willox, and she and her husband died within eight days of each other, leaving a young family of four, David, (my father), James, Alexander and Elizabeth, altogether unprovided for, to the mercy of their friends and the world. They were brought up in some sort of way, but almost entirely without education. Without the control of parents, they were careless of the education then offered. My father remained about Parkhead and became a good weaver. James also learned the weaving, but drifted into a seafaring life for some time, but ultimately came back to the loom. Sandy the youngest of the three brothers went into farm service, but ultimately went into pits as a miner, and settled down in Torphichen, Linlithgowshire.

Elizabeth was brought up by a Mrs. McNaught, who resided in Elba Lane, Parkhead. She also learned the weaving, and when grown to womanhood, formed one of my father’s family, and lived with us for a good while.

We are now getting nearer our own day. My father and mother married young, he about 20, she about 18. My mother had been left parentless also when she was but an infant, her mother dying, you might say, on childbed, the baby (my mother) being only about eight days old. Her father, William Dunn, left with a small family, married shortly after his wife’s death, but did not enjoy his second marriage long, until the Great Reaper gathered him also. Hence, I have never had the felicity of seeing any of my grandparents. The young widow, Mrs. William Dunn, became the second wife of Hugh McPhee, a widower with a family; hence the Dunn’s and McPhee’s became one family, living together until separated by marriage or death.

The McPhees’ were a very respectable family, and my mother was brought up like one of their own, receiving a fair education so far as being able to read and do a little figuring in a passable way. Hughie McPhee was a little man, about 5’ 3” or 4”, but stout and well proportioned, good tempered and as steady as a rock. He had a room and kitchen and a four loom shop on the Great Eastern Road, between Montgomerie’s and the Pump Riggs, and was altogether a bien and well doing man. In this home my mother remained until her marriage, and really never felt the want of her real mother and father. She was the favourite of the family, and it was much against their wish that she married my father, who was reported wild and improvident. They feared for the future comfort and happiness of their favourite, and their fears were, alas, too well founded, and their worst anticipations realised. My father, from the earliest, without being a thoroughly bad man, was thoughtless, careless of domestic comforts, and given to company. His work was often neglected, as were his wife and increasing family, of whom I was the first, being born of the 3rd June 1845. Hence my mother had the whole care of providing for us. She wove, washed and “ca’d pirns”, and did anything that would bring in an honest penny, sometimes helped by her mother (stepmother), and sometimes by a kindly disposed neighbour, who, seeing her struggle and knowing her poverty, lent a helping hand.

I have now brought these family notes down to the date of my own birth, and will henceforth deal with matters more under my own observation. I understand that as a child I was remarkable for nothing but getting wandered, and sitting much alone. I took up with any beggar woman who spoke kindly to me, and would follow them from door to door, holding by their skirts until some neighbour, knowing whom I was, took me home to my mother. Thus, you see, I have been “sib” with poverty of the very poorest class from my earliest days.

One incident of which I have often heard my mother speak, I must here relate, as it nearly disposed of the writer of these notes in rather a tragical manner. I was only an infant of a few weeks old when my mother gave me to a woman named Ann Ogg to nurse, so that she, my mother, might be able to earn a few shillings. She had a loom then in the McPhee shop.

Ann Ogg was fond of a dram, but was said to be a kind hearted woman. Her husband, John, was a pensioner, and Ann, one day, had gone to meet John coming home with his pension, taking me in her arms. How it happened I don’t know, but Ann had indulged too freely, and coming home, having to cross Camlachie Burn, then open at Crownpoint Road, she slipped and fell, and seemed to be in such a helpless condition that she and I must both have been drowned but for some gentleman who had witnessed the mishap, and rescued the drunken nurse and helpless child (myself) from a watery grave. I need hardly say that Ann lost her job, and I was transferred to safer keeping.

The first house that I remember living in was in “Shinty Ha”, through a close leading to a back-land of two dwelling hoses and four loom shops, with two outside stairs facing each other, and nearly meeting at the foot. One of these led to our house, a garret, the window of which looked into the street, Great Eastern Road, and the other led to the two houses above the weavers’ shops, and also a mid-room. These houses were inhabited by two families of the name of Brough, and the mid-room by Granny McAuley, and her son Robin. One of the two houses had been occupied for some time by a family of the name of Hill. Hill himself was so deaf that one had to roar into his ear to make himself heard. The Brough’s were very respectable people, well-doing, and seemed to move in comfortable circumstances. The boys were well clad, and were seldom seen without boots, while I ran about barefooted, bareheaded and in rags. Naturally, therefore, our family and theirs had little dealings, as the boys seemed to look upon me as a sort of outcast. I resented this, and one of them, John, and I became deadly enemies. He was year or eighteen months older than I, and inclined to tyrannize over me. This led to frequent tussles for superiority of the most determined character. Frequently if Jock and I happened to be coming down our respective stairs, we commenced making faces at each other till we reached the foot, when we met and got to grips at once. Then there was commotion in the little court, I remember on one occasion such a battle royal took place, and our legs and arms were so interlocked that it took the united efforts of all the old women in the court to separate us. Of course, with some of them I was the blackguard, the ragamuffin and nae’r-do-weel. He was the snob, well behaved, inoffensive, harmless boy. We grew wiser as we grew older, and each respecting the others fistic ability, we did not fight so often.

Our house was a single apartment, camp ceilinged with two set in bed places. The floor space was certainly not extensive, and our furniture was in keeping with it. The rent must have been small, but small as it was, there was difficulty in meeting it. It was often in arrears, which doubtless accounts for the frequent visits of the Laird, George Honeyman. Here we remained for some considerable time, my father irregular in his habits, and my mother weaving, ca’ing (winding) pirns, and sometimes doing a day’s washing. On the latter occasions we, the youngsters, could always depend on a meal, as she, in addition to her food, received 1/6 or 2/- in cash. It was while we were here, not withstanding all her thrift and toil, that she was induced to hire herself out as a wet nurse, into the family of Campbell of Camsarkin as I heard it pronounced. Here, as elsewhere, she became quite a favourite, and remained until the child she nursed was weaned, but her heart was still at home, poor as it was, with her own family. How we managed during her absence I cannot tell, but we got along somehow, through the kindness of the neighbours and Granny McPhee, who kept an eye over us.

It was while residing here, and during mother’s absence, that I saw the first house on fire that I had ever seen, right opposite our window. The fire originated in what was known as “Paddy Boyle’s Land”, and as the appliances for extinguishing fires in those days were of a primitive character, considerable damage was done indeed the place burned itself out.

What a day of rejoicing we youngsters had when mother returned home, with some little money, and many articles of wearing apparel, bed clothes, and other things given her by the kind people whom she had served, as marks of their appreciation. During my mother’s absence, and after her return, my father took spells of working in the Forge as a labourer. The wage for labourers there in those days was eleven shillings per week, but this magnificent sum did not all come home, George Honeyman coming in for a share of it. He, my father, was also a short time in a foundry in Hill Street, Gallowgate, probably a shilling or two more a week, making up for the difference he had to go to his employment. As I look back through the glasses of memory, in those days, now after something like seventy years, I shudder and wonder how we came through it all; thanking God that he blessed us with such a mother. Among the other changes which occurred here, was my father going to Torphichen, where he remained for some time, working in the Pits in the Armadale district. He took a house in Torphichen and wanted mother to go there too, but she refused, I think wisely, and so single handed she battled with her lot, and in some way kept herself and three or four children. About this time I learned to ca’ (wind) pirns, and between that and looking after the younger ones, I was of some assistance to mother, who wrought late and early at the loom, but oh! There was not much to be made of it.

After some time I found employment with old Hay, the farmer, in Helenvale Street, as a “herd” boy, where I remained for some time, but in addition to herding, I had other duties to perform of a much heavier character. About this time things must have gone hardly with my poor mother, as she had to remove with her two or three children into lodging with a neighbour, who had two or three of a family of her own. Thus there were two families crowded into one apartment. There seems to have been no law against overcrowding in those days, and as for sanitary authorities, I never heard of them. How we got on I cannot tell, it must have been a life and death struggle. I had scarlet fever here; think of it, scarlet fever in a single apartment, with two families crowded together, comprising three grown up people, and 9 or 10 children. It must have been a case of the survival of the fittest. I pulled through though, and I cannot remember that any of the others were stricken down at this time. The neighbours were very kind, and many little things were sent to comfort, amuse and sustain the invalid. Hay’s people, with whom I had been herding, were not unmindful of me, and sent frequently to enquire with more substantial tokens of their regard. The people with whom we lived were of the name of Lightening. Adam, the man of the house was a weaver and one of the more barefaced liars that ever breathed, but not an ill-doing man for all that, as I afterwards came to know him. His penchant for drawing the “long bow” was based on vanity more than any set purpose of evil, and his lies hurt nobody. He had a pin leg and stamped about with considerable dignity of bearing. His wife, Bell, worked at the tambouring, and though they were poor, in the kindness of their hearts, they could find shelter for those still poorer. I respect there memories, but never was in a position to reward their kindness while they were alive. The Lightening’s, as far as I know, have all passed away, and nothing remains of them except the remembrance of their kindness.

How long we remained with the Lightening’s I cannot exactly say, probably about a year. My mother continued at the loom, and seems to have been able to make ends meet in some sort of a way. It was after my recovery that I first learned to throw the shuttle. It happened in this way, during my convalescence, and after, I used to go over to her weaving shop, and sit for long spells beside her, listening to her stories of Auld Lang Syne, and her snatches of song as the shuttle flew from side to side and the dressing rods gradually crept towards the headless. I plagued her often with my questions, and persisted for a long time in asking her to let me try my hand. At last she yielded, and tied up the treadles to suit me. Then with one hand on the lay beside my own, and the other holding my right hand with the driving pin (pluck stick) in it, we made the shuttle skip across the sole of the lay, and I had thrown my first shot. We persevered in this way for a number of times, until she could trust me alone, with her overlooking me until I got a little command of both lay and driving pin, then she could leave me for a few moments.

As yet, however, I was totally ignorant of the other intricacies of the art. I gradually improved, and at last she thought of sending me as an apprentice to one Charles Johnston, to learn the trade thoroughly. This was not a success; I soured at it under the crusty control of Johnston, and threw myself once more on the loan of my companions, participating in all the pleasures and mischief’s incidental to boyhood. After a time I was sent to another task master, but if Johnston was bad, this one was worse. He even struck me, and of course, this I could not stand – sing ho: for the freedom of the fields. I left without notice and he neglected to give me a character. My mother, I have no doubt, had many an anxious thought concerning me. I got into Grant’s Mill, Mile-End, to learn the Rone piecing (no pay) then into a ropework, where I remained for a short time. The pay here could not have been excessive, as I left that, and went to the “tearing” in connection with the Block Printing in Millersfield, and from that to the machine shop, where I had 3/- per week. Here I remained for some time, but evidently not thinking my services not sufficiently remunerated, I left there and went Muir & Brown’s Printwork, about a mile further away, for a sixpence a week more. We must have been pretty hard up in those days, but we had never known anything else. The pay day, my pay day, was every Friday, between breakfast and dinner time, and my sister Agnes, used to come with my dinner on the Friday’s for the purpose of taking home my pay, probably to purchase a dinner for those at home.

Thus we struggled along, until my father, tired of Torphichen, and having no hope of my mother joining him there, returned and immediately took up a house in the Ree, in one of those mansions of two apartments I have already referred to. He set about putting up two looms, one for himself, and the other to let. It was quite a common thing for tramp weavers to hire a loom by the week, at 1/- per week, my mother ca’ing (winding) the pirns. This arrangement might have done very well, but there did not seem to be any improvement in his own character. His periods of industry were irregular and the allurements of company were too deeply rooted to be easily overcome.

The first house we inhabited here was the southmost but one in the east row, and like all others in the two rows, was damp and unwholesome, with earthen floors. The principal piece of furniture was the pirn wheel, a low stool or two, a rickety chair, and the remains of what had once been a dresser, with a few earthenware plates and bowls upon it. Furnish polish was a thing unknown. But my father was a handy man, and to supplement our stock of furniture, made a chair. I think I see it now, 4 paling stabs, two long ones for the back, and two short ones for the front, nailed together in some ingenious way, with rests for the bottom. Laugh at it if you like, but it was serviceable and steady as a rock, and covered by some old cloth or canvas, the crudities of its joins and the knots of its limbs were not seen.

He also made a stool for the opposite side of the fire. This was done by driving four pieces of stabs of equal length into the floor, which was earthen, and nailing a bit of plank on top of them. It had one sterling advantage over all its class, it would not topple over. This when covered over with some coloured remnant was rather attractive in its appearance, though somewhat deceptive, and furnished a standing joke in our family for many a day, which originated as follows: – Incredulous as though it may appear, in this scene of restricted accommodation and limited means, my father kept a dog (bitch), dear old Gem. I remember her well, a quiet, sagacious animal of a bulldog breed of a good class, and as intelligent as an old woman. We seem to have fallen behind in the payment of the license, and after repeated warnings and threatenings, two men called with a barrow to take away our things to roupe them. When they called, some warning of which we had, we determined that they should not find the dog in the house. It was put out through a broken window in the back apartment. The old grey faced “wag at the wa’” was hurriedly taken down, and hidden somewhere, but in the haste the weights were left lying under where the clock had hung. The coast now being clear, the unwelcome guests were admitted, but on opening the door, what was our horror to see Gem sitting at their feet waiting to get in. She had just gone round and through the close, and was the first to enter. The two men proceeded in the execution of their duty, in a somewhat businesslike manner.

“You keep a dog here?” This could not be denied. “Well the license is not paid, and we have the authority to sell off your furniture in default, but eying the surroundings, we are willing even now to make a compromise and let the articles remain of payment of five shillings.” “You can make what you like out of it, but there is not a sixpence in the house.” “Then we must proceed. We see you have had a clock here (pointing to the weights lying on the floor) where is it?” “Away getting repaired.” By this time a large crowd had gathered round the door, execrating the tyranny of the laws in general, and the hardness of the official heart in particular. Some bits of things were taken out and placed upon a two wheeled barrow, when one of the men, noticing what he thought was a cushioned stool by the fireside, made grab at it as a prize worth securing, but found it immoveable, and had some difficulty in hiding his disgust and disappointment. We have often laughed at this incident, and while we could look upon it as a good joke long after it took place, it was no laughing matter at the time. Whether being sick of their job, or despairing of being able to realize as much as would pay the license, as a last resort, the men said “look here, pay 2/6 to the barrowman, and we will let you have your things back.” “I have told you we have not a sixpence in the house.” “Can’t you borrow it then?” I’ll see you dead first,” replied my father with some heat. But some of the neighbours here interposed, and handed over the amount asked for, which was accepted, and our things were put upon the street. But my father was so indignant or so proud that he would not assist to carry them in. There was not much labour in rearranging them.

Speaking of our dog Gem reminds me of an incident that much affected me at the time. She had pups on one occasion which, probably being of a mongrel breed, it was resolved to destroy them. I, being the eldest of our family was appointed executioner. I was to drown them in the quarry hole, a task which I rebelled against with all the energy in my power, but my father’s apron was tied around me. And five or six little helpless things were put into it. Under threat of a mauling I was packed off greeting all the way. The journey was a slow one, though not far. I sat down by the side of the pond, and fondled and gret over them for a good while, but knowing that I dare not go home without being able to say I had accomplished my mission, I at last threw the little things in and cried as if heart would break. One little thing in its sprachling, came to the side. I lifted it out, and stroked it amidst my sobs, but was constrained to part with it, and returned it to its watery sepulchre whence I had taken it. This left a deep impression on my mind and heart, and rather increased rather than diminished my love of animals in after life.

About this time it was decided that I should be a weaver, and under the watchful eye of my father, I made rapid progress, with sundry slaps on the jaw, and such praise as “dunderhead, numbskull etc. etc.” I soon learned to throw the shuttle with some degree of proficiency, and in addition to “dress” my own web, besides some other important particulars, which raised me mightily in my own estimation, and gave me a zest for the loom. This arrangement bade fair, and might have added much to our family comforts, had my father only been steady, and kept an eye on me, but he went long and frequent spells on the batter, and I took advantage of these to run about with boys of a like disposition, often getting into trouble, being chased for trespass, and other misdemeanours, to the great grief of my mother, who must have had many an anxious moment on my account when out of her sight. Here I picked up some new companions, Wm. Morgan, John and James Murphy, brothers, and Patrick Fitzsimmons. John Murphy was perhaps two years older than any of the others, and the leader in every devilment, a fearless lad who would fight, and not always unsuccessfully with anyone stones heavier than himself. Wm. Morgan and James Murphy were two of the best “chippers” (stone throwers) that I ever saw. Their accuracy of aim was marvellous, and many a cat and dog paid the penalty. We were a wild lot, yet never committed to any serious crime, and certainly never came under the “lash of the law” though we often felt the toe of our parents’ boots on our after parts.

There were a few “unco” bodies about the Ree, two of whom I merely mention “Rouse the Bear” and Jock McPherson. The former was a sort of a half-wit, who lived with his mother. She was said to have occupied a situation at one time in the service of a gentleman of some social standing. “Rouse the Bear” whose real name was Adam Mair was of a down looking, sour repellent disposition, of electric temperament. One never knew the moment he might burst into blaze, and then the further from him the better. At first he seemed to take a fancy to me, or rather he tolerated me more than others, and I used to go into his shop for a few minutes just to pass the time. However, his mother asked mine for God’s sake not to allow me in any more, as Adam was in a fearful rage at me, and threatened to cut my throat.

He said I stood and whistled about him. This stopped my intrusions, and I am afraid, added one more to his list of tormentors. One had only to look at him steadfastly to extract some of the most fearful of oaths, with the enquiry “what the hell you were looking at.” Should you happen to cough in passing him “hell” nor you would choke “you bastard” was likely to be the sympathetic salutation, but the climax of all was when you shouted “Rouse the Bear.”

It seemed then as if the hell within him had burst in overwhelming force. The game was dangerous in the extreme. He was light-footed and reckless in the use of stones. The chase was exciting and hazardous, and many narrow escapes were made.

Another character of a less dangerous nature than “Rouse the Bear” was John McPherson, of whom I have treated at considerable length elsewhere (see Black Jack o’ the Ree) a poetical sketch of mine which has been in print for a considerable time.

It was in the Ree that my brother John was born, and it was here I remember teaching my brother Alexander to walk, as he was often placed under my charge. You might wonder that in a house of the dimensions that we lived in, that we should be able to keep lodgers, yet this we did. We had with us for a considerable time a man of the name of John Lawson, nick-named Jenny Kessock, a pretty wet hand, but evidently a man of considerable education and intelligence. He was a splendid reader, and often entertained our family by the stories he read, such as “Wilson’s tales of the Borders”, “The Life of Wallace” and numerous other tales.

The Scotch ones always had a particular attraction for me, and I have no doubts that it was here that the seeds of enquiry were first sown in my mind. He and I slept together in a small bed, which my father in the exercise of his constructive genius constructed behind the kitchen door, thus if limiting still further the floor space, helped to furnish the house.

Not withstanding my father’s designation of “dunderhead” and my extreme youth, I seem to have picked up a fair knowledge of the weaving trade, and passed from the plain one shuttle, two treadle class of work to that of many shuttles and many treadles, required in the weaving of flounces, shawls, petticoats, and shot-abouts, and even before I reached my twelfth year could adjust the webs of men who had a family. Indeed I seem to have been something of a phenomenon. The intricacies of the loom, though they puzzled me some, had a strong attraction for me.

Weaving in these days, especially in the evenings and dark mornings, was carried on under much greater difficulty than in later years. There was no gas light, and oil lamps were in general use, the light from which made the “darkness visible” and was attended with considerable danger, sparks from which were apt to fall or be knocked on to the web. I remember this happened on one occasion with me, and had it not been for the presence and promptness of my father, the result might have been disastrous

People in higher walks of life may well wonder how the poor eke out their existence, but there seems to be a genius of adaptation implanted in them at their very birth. Means and methods that would be totally ignored by the well to do, are developed by the poor until they may be classed among the fine arts. Let me give you an instance. Coals were sometimes at a premium, and could not be had. The supply at the pits may have been alright, but the wherewithal to purchase was wanting, so it was no uncommon thing for the youngsters to be sent to pit ash bings to gather cinders and chips of coal to eke out the domestic supply. Another method of securing the black diamond was, and this was a frequent one about the Ree, to offer about a finger length of small twist tobacco to the coal carters in exchange for a piece of coal, or a small hank of cord for cracks for their whips. We usually expected more for the hanks than the tobacco, and were not disappointed, at least, not often.

The Ree was well situated for this mode of barter, passing south along the Ree road, where there were no houses; we reached the London Road, then one of the main arteries of the city’s supply of fuel, and along which there was a great amount of carting, railways not being so numerous than now, and carting being the prevailing means of supply. On reaching the London Road we waited there until the carters came along, when all we had to do was expose our articles of barter, when a lump of coal was exchanged for the tobacco or whip cord. These transactions were intermittent, and not altogether without risk. The two farmers whose properties we had to pass to reach the London Road, objected to our passing that way, so we had to see that the coast was clear. Then we had to see that no one witnessed the transaction who was likely to interfere. We instinctively felt that we were doing wrong, but something of the same spirit that influenced the smuggler around our coast, lang syne, seemed to whisper we were doing right. Many a cheerful blaze from this source had gladdened and warmed the fireside of an otherwise cold and cheerless home.

The Ree Road, as I have already said, was a favourite recreation ground for young and old, and on Sundays it was particularly well patronised, groups reading the newspapers and discussing the events of the week, others expatiating in the merits of the principals in some prize fight, or the result of some cock fight. Talking of fighting reminds me that I once saw a real set dog fight here between our own bitch Gem and another. It was a most repulsive sight, and nearly ended in a man fight. I don’t remember which dog won, ours or the other, but Gem bore several marks of her opponent’s teeth, and I have no doubt the other had impressions of hers.

There was an unusual arrangement with regard to the gas here. One meter for each row of houses built into a little recess in one of the entries, under lock and key. Each of those using the gas took charge of the key in turn. The hour of putting on and shutting off the gas being fixed from time to time as required by the lengthening or shortening of the day, and all paying according to the number of lights they had. This arrangement seemed to work very well, but there was a danger, and a big one it was, that if any one neglected to turn off his burner at night when the meter was turned off, the gas escaped in the morning when it was turned on, at the great risk of suffocating those that had neglected to turn off their burners the night before. This danger had been foreseen, and instructions given to every one to exercise the greatest care and attention, but not withstanding these instructions and the awful consequences that might ensue, this very thing happened, and a whole family were nearly launched into eternity during their sleep.

A family named Devine had been working late one night, and taking advantage of every minute they had of the gas, found themselves in the dark by turning the meter off at the regulation hour. They neglected to turn off their burners, ad went to bed. They were late risers, and in the morning before they were up, the gas was turned on at the meter, with the result that it escaped through the unclosed burners, and soon filled the house, though it was anything but air tight.

Someone having occasion to call upon the Devine’s in the early morning, found the door unbarred, and a strong smell of gas pervading the whole entry. An alarm was immediately raised, and the door broken open, when it was found the whole family, six or seven in all were insensible from the effects of gas poisoning. There was an awful turn up in the Ree that morning, as one after another of the insensible family were brought out into the open air. The cause of this disaster was at once ascertained, the two shop burners had been left open the night before, and as soon as the gas was turned on in the morning, it commenced to fill the house, a narrow, narrow shave indeed for the Devine’s, and an object lesson for all. Doubtless all profited by it, but what precautions, if any, were taken to guard against future occurrences of a like character, I am unable to say.

The McDonald’s

We remained at the Ree for some considerable time, three or four years perhaps. Even at the present moment I could name almost every family then in it, but in passing, only mention a few. First the McDonalds, Willie one of the sons and I became very chummy. He was a wild boy and shrank from no devilment. His father was one of the best readers of Scotch stories I have ever listened to, and often when he and a group of his neighbours were seated in the Ree road, rehearsing the adventures of “Archie Armstrong on the storming of some borders keep or castle” I was an entranced listener, my young blood leaping through my veins with all the force and fire of dawning romance, or my eyes filling with tears over the sufferings and sorrows of Scottish Covenanters.

The Hendry’s

Another of the families was the Hendry’s, a Roman Catholic family. There were two sons and a daughter, William and Peter. The sons were cronies of mine, especially Peter the younger. The old man was very fond of a fighting cock, and kept one, a beauty, but some envious neighbour got another, and the two cocks, meeting, fought until Hendry’s beautiful bird was simply a bundle of bloody feathers. Oh, such a row as there was over it. Old Hendry went mad, he challenged the owner of the opposing cock to mortal combat, or any one who would take his part, but the turmoil blew over as such things usually do.

The Murphy’s

The Murphy’s, to whom I have already referred, lived in the back land. Old John, the father, was a bit of a character, though like the rest of us, steeped in eternal poverty. The following incident is told of him, the accuracy of which I do not vouch for. A peddling clock merchant called upon John one day, and insisted on selling him a clock. John pled his inability to buy, but the peddler would not be denied, and said he would just hang it up, and the payments could be made at one shilling a week, or so. After some haggling as to it’s price, the clock was hung up, what was called a beautiful American one in a finely varnished case. No doubt it looked grand, though somewhat out of place among the other articles of household plenishing, but whether it was a good timekeeper or not was never thoroughly known. The vendor was not well away when the clock was taken down, and sent off to the pawn, and furnished the last meal they had had for a long time. A week or so afterwards, the clock man called again for his first instalment, and not seeing the clock had asked John “What he had done with his clock” “oh” replied John, “the clock, we ate it.” “What, you ate the clock,” “Yes, and we could have eaten the man who sold it as well.” It is said that the vendor of clocks didn’t pause to ask for his instalment, but took an abrupt leave of John, and was never seen in the neighbourhood again.

Harry Hutton

Wee Harry Hutton was another of our local worthies. Harry disappeared sometimes, but usually turned up to his loom again. This was a great mystery for some time, until it was discovered that he went away on musical excursions occasionally, for the purpose of replenishing his larder. He played upon a tin whistle, and charmed the natives of distant villages by the exercise of his genius. He seemed to make a good thing of it, as often on his return from these excursions there was a “blow out” for a few days before he tackled the shuttle again.

I need hardly specify any of the other families as there is nothing of outstanding interest to note. Their home life was much alike, all were poor, but there are degrees in poverty as well as in the university, some were poorer than others. This depended very much on the industry of the family. Sometimes there was a run of good work, when there was a manifest improvement in the conditions. At other times there was dullness and scarcity. I remember while we were here, there was a period of dullness, entailing awful sufferings, work could not be had, we were starving. Soup kitchens were established throughout the town, and the Corporation of the city distributed among the suffering people little paste board tokens bearing the City Coat of Arms which was called “Wee Men” owing to a representation of Saint Mungo being on them. These were very sparingly distributed, and were accepted by shopkeepers as current coin. The Corporation also undertook the supply of coarse webs quality, called “Provost Webs” whereby a starvation remuneration could be made. I wove one of these webs, and thought it a Godsend to get it. We came through it all, but how I cannot tell.

Mrs. Auld, the U.P. minister’s wife was very good to the Ree people at this time. Through her influence articles of clothing were distributed among the most needful and deserving. Boots and stockings for the children, petticoats for the women, and blankets for the bed were carefully distributed, but let me tell you never one of these articles came our way. I suppose we were considered outside the pale of redemption, yet not a family in the whole place was more needful. Looking back on these times I cannot blame the minister’s wife or anybody else. My father’s improvident habits were sufficient to bar the door against all assistance of a charitable character, yet had they known my mother’s worth, thrift, care and sufferings, they must have lent her a helping hand.

Sometime after this my father and I went into the factory at Crownpoint to work. We remained there for some time. Then he took a four loom shop and room and kitchen in the Shinty Ha’ where we remained for a year or two. It was while here that I went to Torphichen. It came about in this way – my aunt Elizabeth, my father’s sister, who lived here with us, instilled into my mind the idea of trying to better my prospects as a weaver. I could never be anything but the companion of starvation. “Go to Torphichen” she would say, “and you may make big money in the pits. Your uncle Sandy will look after you and see you in a fair way of getting on.”

This reasoning was too much for me. I took her advice, and without a penny in my pocket, shoes on my feet, or a bonnet on my head, I set out on a tramp of something like 26 miles, ignorant of the road, ignorant of the place, and ignorant of the world. You will find a sketch of my experience on this journey in the autobiographical remarks in “Poems and Sketches.” After some time in Torphichen, I returned to Parkhead, and tackled the loom again, this time in the six loom shop, where my father had two looms. He had evidently given up the four loom enterprise already referred to, and our house was in Steen’s Court, a room and kitchen here.

My younger brother William died – poor Wullie – with care comfort and attention he might have been living still. He was a big-hearted, cheery boy, a favourite with all who knew him, and was said to be as “auld farent” as a man.

The six loom shop, as its name indicates, contained six looms. These were occupied as follow – William Fail, old Alex, Agnes Hammond, my uncle James (the sparrow), my father and myself. William Fail was a quiet, stout, steady man, but not too fond of work. Alex, the pensioner, lodged with him, and he was as deaf as the proverbial door nail, or almost so, and except at pension time was as regular as the clock. He used to watch me as I measured myself against the side of my loom, so anxious was I to become big, my chief ambition then to being a man.

Agnes Hammond was an orphan girl who had been brought up by Mr. and Mrs. McPhail. They had no family of their own. She was a good weaver and stuck very closely to her work. She remained with the Fails (McPhails?) until her marriage with Archie Harvey. The Fails owned three of the looms, and my uncle the other three, two of which were hired by my father. I wrought pretty steadily here, and made considerable improvement in my knowledge of the trade, not withstanding the frequent absence of my father.

I must have been about ten or twelve years of age about this time, and I think it was in about this time that I began to feel my want of education. I hardly knew a letter of the alphabet, any scrap that I had picked up a few years before had almost entirely vanished. It was my good fortune here to get acquainted with a lad named Mason, who was a few years older than I, and he spelled out some lessons to me, and showed me how words may be written on paper. I became interested, and gradually acquired a taste for information, which has been with me through life.

About this time or perhaps earlier, I began to be noted amongst my companions for “making poetry” as they termed it, which was simply a knack I had of turning the simplest phrases and incidents into rhyme, but this was a wonderful performance in their estimation, and one which some of them tried to imitate sometimes. James Mason used to scribble down some of my blethers as I rehearsed them to him, and he seemed to take as much pride in the task as I did. Thus it was that I afterwards had some pieces in print before I could either read or write, the “Penny Post” and the “Hamilton Advertiser” being the medium through which we enlightened an ignorant public. Oh! What triumph I felt on first seeing my initials in print.

Another source of instruction to me was my acquaintance with William Frame, a boy a little older than me, and one of my dearest companions. His family was rather better off than ours, and his education had not been so entirely neglected. He could read a little and write less, but his taste for information was equal to mine, and this further encouraged me to persevere. Latterly an epistolary correspondence was commenced between us, of a somewhat singular character. We delivered our own letters to each other personally, as we lived in easy reach, and often the writer waited till the correspondence had been read so as to help the reader to decipher the hieroglyphic characters intended to convey our meaning. Willie was much my superior at this game, but I closely followed and imitated as nearly as I could. We adopted this plan as a means of mutual improvement, and we both benefited by it. Our paper was any scrap of white paper we could find, and our lines were, well, varied in regularity, being written at all angles, but we improved and continued this novel correspondence for a long time.

On the same stairhead with Mr. Fail lived a very remarkable old woman, she lived alone in a single apartment. I don’t know what her right or full name may have been, but she never got anything but Granny Looggie, a kindly old body, not very tall, about one hundred years old. She died at the age of one hundred and three. We youngsters often used to go in and see Auld Granny. I understand she had some peculiar habits, one of which was putting the butter in her tea instead of on her bread. She was said to have followed her husband through all of the Peninsular War. What was her means of support I am unable to say.

There were four tenants on this stairhead, my Uncle James, William fail, Granny Looggie, and James Mason. The latter was my secretary; it was he who used to jot down my rhymes.

Parkhead changed somewhat in character about this time, indeed the change had been going on for some time. A great number of new weavers came about the place, chiefly from Girvan and Maybole. These were principally coloured weavers, that is, their work was of petticoat, plaid, shirting and skirt class, and was quite distant from the fine lawn and muslin work of earlier times.

Besides, the Forge began to extend and other collateral branches of industry were introduced, which brought a goodly number of “incomers” around the place, who, of a rougher character of the old, or original residenters, soon assimilated with the others, and became one people. There, however, always remained a mark of division between the colliers’ and the weavers, to such an extent as to culminate in an occasional stone battle, in which not only the boys of either side participated, but grown up men as well. I have good reason to remember those stone battles, being put “hors de combat” in one of them. A battle lasting intermittingly for three days took place on one occasion, and, of course, I was there and in it, until I was put out of it in the following summarily manner. I was in the front line of our side, and probably with the object of showing off a bit, I advanced against the enemy rather incautiously, and got pinked on the bridge of my nose for my temerity. I suppose I was knocked senseless – I might have been killed – and carried to the rear. Immediately the cry was raised that Davie Willox had been killed, and this stopped hostilities, for the time being, at least. I never took part in a stone battle after that and bear to the present day slight marks of my last one.

Original Families

The old original families became lost as it was in the great influx of strangers that had taken place, chiefly English and Irish, or as Granny McPhee used to call the latter” Brish” but I remember a few of the old originals, whom I name, many of whose representatives are still with us, well not many now. The Willox’s, Brownlie, Barr and Arrol of Burgher Street besides Little, Fleming, Chalmers, etc, Turnbull, McNaught, Horn, Stout of the west end, Marshall, Rodgers, Wilson and Whitelaw of Dalmarnock Street, Hamilton, Howat, Carey and Turner of New Road (Duke Street), Marshall, Moffat, Miller, and McArthur of Westmuir, Lawson, McLean, McPhee, Riddell, Miller, Crawford, etc., of Great Eastern Road and Shinty Ha’. I might add to this list indefinitely but it could serve no good purpose, so I only mention such families as has come under my more particular observation. There are others such as the McEwen’s and Abernethy’s and others that I may mention as I go along.

Willie Barr

Lang Willie Barr had a big family and had the six loom shop in the Big Land. He was a man of great respectability, and was an elder of Tollcross U.P. Church. I remember on of the Rev. Mr. Auld’s sons, David, learning to weave with Barr. How many ministers send their sons to learn weaving nowadays?

Brownlie

Brownlie was another decent steady going fold fellow, he lived “but-and-ben” with our old man, and had the four loom shop. Of the Little’s and Arrol’s, it is said that old Little so wormed himself into the good graces of Arrol that he. Arrol, left his little property at his death to old Little, cutting out his own son, Walter, who I suppose was a little wild, but who, as I knew him later turned out a good man. He was best man at my father and mother’s wedding. He, Walter Arrol, must have been married at the same time as my parents, as their first child, a girl, was born in the same hour as myself.

The Marshall’s of Dalmarnock Street

The Marshalls of Dalmarnock Street were another very respectable family. One of their daughters, Jeanie, I think, married James Hamilton of new Road (Duke Street), who in later years became a magistrate of the city – I was at his marriage. I will have occasion to refer to him more fully by-and by. On the other families in this street I have not much to say, they were mostly decent weavers.

The Turnbull’s, McNaught’s and Purdon’s