By

Charles MacEwing

PREFACE

CIRCUMSTANCES have permitted me little more than six months to gather together the particulars embodied in the accompanying sketch, which I have undertaken at the request of the Church Management. To make it as satisfactory as could be wished the writer would have needed, considering the multifarious duties of a minister’s calling, almost as many years. Much interesting information connected with the district is no doubt likely to reward an exhaustive study of authorities. The examination which, of necessity, I have been able to give them, was but a hurried one, and this must be my apology for any serious omissions or mistakes.

My thanks are due for valuable assistance to Mr. Hugh M. Robertson, Messrs. Andrew Paul & Company, writers ; Mr. Walter Buchanan, Dunclutha, Tollcross; Mr. James Mair, B.Sc.; Mr. Adams, Mitchell Library ; and Mr. William Roy, Tollcross Road.

I have in the writing of these pages sought to avoid everything that might appear to be a raking amongst the ashes of extinct controversies, or that could be construed into an offence against tender susceptibility.

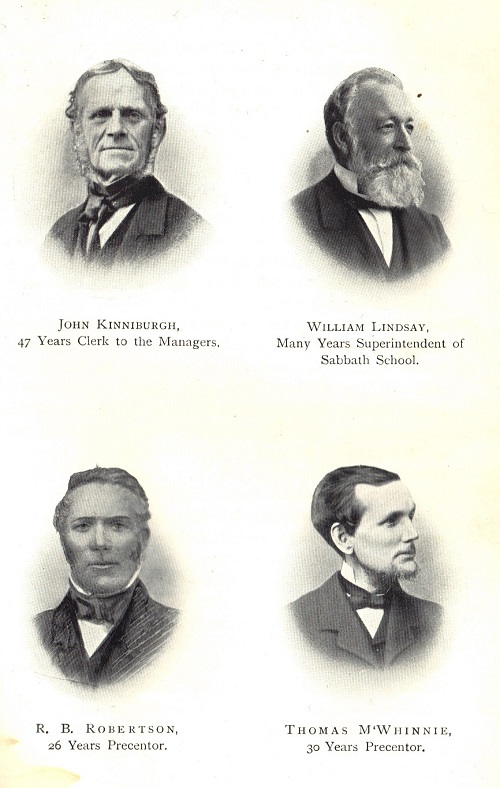

Mr. Robertson furnishes the sketch of the late Mr. John Kinniburgh.

C. MacE.

CARMYLE AVENUE, TOLLCROSS,

September, 19o6.

CHAPTER I

CROSS OF “SCHEDINESTOUN”

THE rights and customs granted to the burgh of Rutherglen at its erection into a burgh royal by King David (1126), and confirmed by King William some forty or fifty years later, extended over what was once nearly the whole of the district of Glasgow, then only a bishop’s burgh, and not until the seventeenth century entrusted with the election of its own magistrates. Consequently a collision of interests between Rutherglen and Glasgow became inevitable. But Alexander II granted (1226) to Bishop Walter a charter which forbade the provosts, bailies, or officers of Rutherglen to take tolls or customs in the town of Glasgow, or nearer then the ” Cross of Schedinestoun,” as ” they used formerly to be levied.”(1 – Reg. of Glasgow, p114) Sir James Marwick supposes the object of this charter to have been the prevention of future disputes. If so, it was not wholly successful, since for long afterwards Rutherglen continued to oppress the bishop’s burgh. William, Bishop of Glasgow, complains (1449) of disturbance and impediment to trade, and James II issued an ordinance forbidding “any hurtying and prejudice to the privileges and customs granted to the kirk of Glasgow of auld tym.” “Nane of yhour said burrows, na nane vtheris cum wythin the barony of Glasgow, na wythin ony landis pertendand to Sanct Mungoe’s Freedome to tak’ toll or custom be watter or land.” (2 – Glasgow Reg., pp. 369-70)

This “Cross of Schedinestoun” has been variously located. The probability is that the situation was at the west end of the village of Tollcross. At this point the road from Rutherglen via Bogleshole Ford—a very ancient crossing—and Shettleston to Falkirk and Stirling, intersects the old Roman road to Glasgow, which in the village forms Main Street. This road was one of the two great arteries of traffic which ran into Scotland from the south. The view here given is somewhat supported by Sir James Marwick. “That portion of the lands of Shettleston on which the cross stood (3 – There are, so far as I can discern, no traces of a symbolic stone cross ever having stood at the place where toll was exacted, although the likelihood is that such a stone was once in existence) was probably what was known as the ‘ two-merk ‘ land of ‘ Towcorse,’ now called Tollcross.”(4 – Charters and documents relating to the City of Glasgow, p. 526)

The name is ancient although the village is comparatively modern. The old spelling is various Towcors, Towcorse, Towcross. The first syllable has given plausibility to the supposition that it is derived from the flax which at one period was largely grown and manufactured in the neighbourhood, and from which the Rutherglen authorities would be certain to exact the legal due. But the tol or tax at the cross would be levied on many things other than manufactured flax.

The truth is that the form in the first syllable is old Scottish for the Anglo-Saxon “tol” or “tel,” signifying to count. Tollcross means the cross of levying or exacting by counting goods so as to take the “tol” or “tax.”(5 – My friend Mr. Hugh M. Robertson writes, “The tellers ill our banks are a fine instance of the survival of the ancient meaning.”) Instances are not infrequent showing a connection between ancient crosses and ancient exactions upon trade, and Dr. Stewart specifies two examples which correspond to the “Cross of Schedinestoun.”

The lands of Tollcross were originally much more extensive than in later times, including until early in the eighteenth century Easter Camlachie, which was known as ” the Little Hill of Tollcross,” and is now called Janefield, or the Eastern Necropolis.

As concerns Shettleston there are numerous forms of the ancient name. In a charter dated Jedwarth, 29th October, 1226, it is Schedenstun. In another, of the sixteenth century, dated at Holyrood in favour of Walter, commendator of Blantyre, it is Scheildiston. In a similar document dated at Dumbarton, 26th August, 1591, it is Scheddilstoun. The truth is that in the matter of spelling each ancient conveyancer seems to have been a law unto himself. I have counted no fewer than nine different forms of the word, and there may easily be more, the commonest of which appears to have been Scheddylstoun.

The name seems to be derived from Villa filie Sadin,(1- Origines Parochiales Scotiae) so called as some suppose from a daughter of St. Patrick’s brother, but more likely from some Saxon colonist, and is enumerated among the bishop’s (of Glasgow) possessions so early as 1170. It has, of course, no connection with the industry which in modern times led to the vulgar supposition that Shettleston was a corruption of Shuttleston.

The lands of Shettleston up to the Reformation were held by the bishops of Glasgow under various royal charters. On 12th September, 1241, Alexander II granted to Bishop William Bondington, Chancellor of Scotland, a charter to hold lands around Glasgow. Among those enumerated is “Schedinistun,” with the usual penalty attached of ten pounds (Scots) for offences committed against the vert or venison—so early were the game laws in existence, and so early were there poachers, (2 – Register of Glasgow, p. 147 )

The ancient surface of the parish was largely a forest of bush land or moss, the memory of which still survives in the names “Eastmuir” and “Westmuir,” in which may have disported the wolf, deer, and wild boar. The valuable work published by the Bannatyne Club entitled “Origines Parochiales Scotiae,” suggests that ” the legend which represents St. Kentigern as miraculously compelling the wolf of the woods to join with the deer of the hills in labouring in the yoke of his plough, may preserve a memory of the fact that those animals abounded there.”

It would appear that in 1170 there was a church or chapel in the village, but no traces of it are discernible in the subsequent records of the diocese. The lands of the Barony of Glasgow, including Shettleston, were confiscated to the Crown at the Reformation, and great lords whose only right was might rushed in to divide amongst themselves the spoil.

Carmyle originally appears as land gifted by Bishop Herbert of Glasgow (1147-1164) to the Cistercian or Bernardian Abbey of Newbotle, to which the Monklands belonged. The earliest occurrence of the modern name of Monkland as applied to land is in a permission of Walter, the Steward of Scotland (1323), to the monks of Newbotle (Newbattie), giving right to passage for their goods and cattle through his barony of Backis to their own, called the Monkland.

The parish as it existed before the Reformation was about twenty miles long, with an average of three in breadth. It was divided about 1640 into the parishes of Old and New Monkland. Long before this date (1 – Statistical Account of Scotland) the lands had been feued out to particular heritors, some of whose descendants are still in possession.

As early as the fourteenth century the parish of the Monklands was so known. But there was a more ancient name which had become lost until comparatively late researches brought it to light. This was Badermanoch or Badermonoc. The ancient church of Badermanoch or Monklands stood on the site of the present church of Old Monkland. Badermanoch, whether applied to church or land, ceases to be met with after 1241. In 1509 the vicar of Cadder, also vicar of Monkland, gave an endowment of twenty shillings “yeirlye to the priest of the Monkland, and to the curat of the Monkland ten shillings yeirlye” to ” pray for him daily in their mess” (mass), and to “compeir in the kirk of Monklands on Salmes daye (All Souls’ Day) eftir nwyn, and thair to say exequias mortuorum, with mess (masi) on the requiem on the morn for his faderis saule and his moderis saule, and his ain saule,” which is the earliest occurrence of the name ” Monklands ” for the church which seems as yet to have been met with.

These monks of Newbattie had a grange at Dunpeldre or Drumpellier, which, with the lands, was granted to them by Malcolm III in “perpetual alms,”,and free from all secular exaction. The larders, cellars, and stores of this Drumpellier grange were doubtless seldom ill stocked; for it seems the monks of Newbotle were excellent agriculturists, excellent fishermen, excellent woollen manufacturers, and excellent miners. They are said to have been the earliest workers of coal in Caledonia, and were never at a loss for good fuel, any more than good flesh, good fish, good salt, and good wool. If they were jolly and well fed, they were also a hard working fraternity, adding in no small degree to the civilization of the country.

Carmyle, Kermil, or Karmyl is said to come from the Gaelic Carr-maol or Cathair-maol, signifying “the bare town.” Should this be the true etymology, the reason may not be difficult to find. The strips of soil immediately in the neighbourhood of river banks were early cultivated—an antecedent, probability, the soil being in those localities alluvial and very rich. It has already been observed that most of the land to the north of Carmyle and Tollcross was originally forest and brushwood alternating with moss, giving excellent cover for wild animals. The lands close to Carmyle being1 alluvial were probably cleared at an early date, so as to give room for successful agriculture. The appellative “bareland” would, in the circumstances be quite appropriate, in contradistinction to the uncleared land lying towards the north. The district was agricultural from time immemorial.

Bishop Cheyam of Glasgow (1268) appears to have purchased the lands of “Kermil” from the monks of Newbotle for the support of three priests to celebrate mass in the church of Glasgow for the weal of the souls of Archdeacon Reginald of Glasgow, and all predecessors and successors. The Carmyle mill, which is still busily grinding, seems to have been a very ancient factory, having been built originally by Bishop Cheyam, and is excepted in that worthy bishop’s dedication of the lands to the above-mentioned purposes.

CHAPTER II

THE OLD FAMILIES

The lands of Tollcross are associated from a very early period with the family of Corbet. Roger Corbet was a baron of Scotland, and swore fealty to Edward I. (1296). He belonged to the family of MacKersten, a branch of which “for several centuries resided in Clydesdale.”(1 – Ragman’s Roll) This is said to be the Tollcross family.

Archbishop Boyd, under a charter of 1580, grants to “Gabriel Carbart” of Hardgray several lands in feu, including the “two-merk” lands of ” Towcorse,” at that, time occupied by ”Carbart” and his sub-tenants-This grant was confirmed by a charter under the Great Seal in October, 1582. (2 – Reg Mag. Sig., 1580-1592) The Commissary records of Glasgow mention a “James Corbet of Towcors” at the beginning of the seventeenth century. At its close there is a Walter Corbet of “Towcorse,” the armorial bearings of whom are given by Nisbet (1722) in his “System of Heraldry.” A Corbet of ” Towcors” who lived before the American War was an enemy of smugglers, in this antipathy quite out of sympathy with many of the landed proprietors of his day, who would have sided with old Bertram of Ellangowan when he defended the smugglers on the ground that ” people must have brandy and tea— and then there’s short accounts, and maybe a keg or two, or a dozen pounds left at your stable door, instead of a lang account at Christmas from Duncan Robb, the grocer at Kippletringan, who has aye a sum to make up, and either wants ready money or a short-dated bill.” In this Corbet’s time smuggled goods consisting of rum, brandy, tea, tobacco and silks were landed on the Ayrshire coast, carted to Beith, and thence taken to Glasgow on horseback. To pass the old Glasgow bridge would have been to court great risk of arrestment, consequently the round-about route via Dalmarnock Ford was usually the one to which was given the preference. Corbet observing a man on horseback making for the ford, slung across the back of whose animal were two casks, ordered him to halt. The rider paying no attention, Corbet pulled his pistol, and shooting the horse dead, made a seizure of the spirits. Whether Corbet ever gave up the casks to the authorities, old McUre, who relates the incident, sayeth not. The connection of the Corbets with Tollcross terminated finally in 1810. The last of the Corbets of Tollcross were Major James Corbet and his brother, Cuningham Corbet, and their families. (1 – An old pamphlet in the Stirling Library says that the representative of the Corbels succeeding to the estate of Duchal changed his name to Porterlield )

Mr. Walter Buchanan, Secretary of the Clyde Ironworks, supplies the undernoted particulars with reference to the Dunlop family:—

The Dunlop family (originally hailing from Ayrshire no doubt) have been for two centuries or more associated with Glasgow and its environs, Garnkirk, Carmyle, Cambuslang, and Tollcross. They rose to more eminence and distinction at the development of the tobacco trade between Virginia and Glasgow. John the Provost, and James, of Petersburg, Virginia, were pioneers in this business, as also in the early banking houses of the city, and here was laid the foundation of the family fortunes. They became landowners at Garnkirk, Rosebank, and Carmyle long before their immediate association with Tollcross, which arose out of their coal mining industry. They worked coal, in the days prior to James Watt, necessarily at shallow depths, and practically but skimmed the surface of the coalfields of this district, which have since yielded undreamed-of millions of tons of fuel.

In the beginning of last century the farms of Maukinfauld, Easterhill, Braidfauld, and Fullarton were studded over with shallow pits, which worked the thin surface seams and gave employment to most of the small population. The establishment, as an offshoot of Carron Works, of the Clyde Ironworks in 1786, had already increased the working population by an access of tradesmen, chiefly moulders and ironworkers. Guns for use in the Napoleonic Wars were then in much demand, and the Clyde Iron Company was founded primarily to meet this demand.

The original granter of the site for the church William Caddell of Carron—was the chief of the first partners of the company; the name still survives in the ownership of Carron lands. Another name of later importance was that of Outram. Joseph Outram was manager at Clyde, and in 1805 (the year before the feu was given off) there was born to him a son George, who came to be founder, editor and proprietor of the Glasgow Herald. This George was also the author of one or two inimitable Scottish poems, which carry his name down to the present time, and will keep his memory green even longer than his famous journalistic enterprise.

The Corbets of Tollcross or Towcross, whatever their penchant, do not seem to have been ambitious to join in the rising industry of coalmining, and their lands were in 1810 bought by Colin Dunlop of Carmyle, who was later M.P. for Glasgow in the Whig interest, and a noted son of a noted father. It should be remembered that a large part of Tollcross is really on the Carmyle estate, the church itself being on the lands of Auchenshuggle, which are no part of the original Tollcross. This Colin Dunlop, a man of energy and enterprise, soon afterwards acquired the Clyde Ironworks, and thus became the principal, if not indeed the only magnate of the district. His career was chequered. His very energy, like “vaulting ambition,” overleaped itself at times. In popular language he frequently put too many irons in the fire, and spoiled his whole enterprise. Withal this Colin Dunlop was a man of remarkable parts as well as of indomitable industry, and it was in his regime that the remarkable discovery at Clyde Ironworks of the hot-blast system by James Beaumont Neilson was made in 1829, which revolutionised the iron industry of Scotland and the world. If he who makes two blades of grass to grow where one grew before is to be reckoned a benefactor of mankind, then he also who makes one unit of heat do the work of ten may lay in a claim for praise. This practically is what Neilson did under the auspices of Colin Dunlop, and at Clyde Ironworks, Tollcross, in the early years of last century, and the district must be held to have earned a niche in the temple of industrial fame, which will not be forgotten even when it becomes wholly merged in the great city of Glasgow.

Colin Dunlop died at Tollcross in 1837, being succeeded by his nephew, the late James Dunlop, who was a well-known figure to most of the present generation, though it is well nigh three quarters of a century since he took possession here.

I was, for many years, associated with the late James Dunlop of Tollcross, who was connected for a long life-time with Tollcross. He built the present Tollcross house in the year 1852, so that the house is not old as mansion-houses go. It took the place of a house of very meagre dimensions. I have still in my possession the correspondence with architects and builders, and it is of interest to know that the beautiful arrangement of trees in the glen, whereby variegated foliage in Spring is assured, and the fine lime tree avenue leading to the house, was the personal selection of this lover of woodland. Mr. Dunlop had this charming trait to perfection. He was not a horticulturist or a botanist, but he was simply an idolater of the beautiful in trees, and whether in his own estate or in others in which he had interest, woe betide the despoiler upon whom he laid hands.

This James, along with his brother Colin Robert, was of the Edinburgh branch of the family and bred to the law, and took ever a lawyer’s view of business. He practised as a solicitor in London before coming to take partnership with his uncle in Clyde Ironworks some 70 years ago. He was a man of punctilious regularity of habit and life, and of strict, and even at times what might be called by the world quixotic integrity. In 1857, when the Western Bank failed, in which he was chairman of directors, he voluntarily-stripped himself of his whole fortune and gave about £100,000 (which at that time was a very large sum) to the bank’s creditors. Other wealthy directors were not so generous, and the case being taken to Court, it was held they were in no way legally entitled to meet more than their ordinary shareholders’ responsibility. But Mr. Dunlop was unaffected by the decision. To him it was a matter of honour to do as he did, and so it remained. It turned out in the sequel that had others done as he did the bank’s credit would have been restored, and probably not a penny would have been lost to any one in that great disaster.

He was autocratic and even severe in his dealings with men, but never consciously unjust; and perhaps he was unfitted in many ways for commerce. He had not the old Dunlop instincts for bargaining in the marketplace, and he lacked, not the shrewdness or balanced judgment of the man of affairs, but rather the quick perception of personal advantage which goes so far towards commercial success. As a magistrate and county squire he was in his element, and he brought to public duty a conscientiousness and distinction which magnified the office and dignified the layman’s administration of justice. Proud and reserved in manner, he was still of most kindly disposition, and had a happy humour that bubbled over in anecdote and reminiscence in company. The finer traits of his character came into fuller blossom in the later years of his life, and it is matter of great regret that Mr. Dunlop, with his unique accomplishments, did not leave behind some book of reminiscences of the period in which he figured. It would in all probability have been of abiding interest and rivalled the best things of the kind which the nineteenth century has produced.

Dr. J. O. Mitchell writes (1- Old Glasgow Essays, p. 341)—”Beyond the grimy suburb of Parkhead a high wall, with gates and lodge, skirts the turnpike road on the north. Forges and foundries, coal pits and ironworks have vanished; the only building in sight is a turreted mansion standing in a wooded demesne; a burn winds between sloping banks with shrubs and flowering trees; rabbits scurry among the bushes, and rooks wheel above the tall elms.” The Tollcross policies are now a public park, the property of the Corporation of Glasgow, one of the most beautiful of the city.

The Grays of Carntyne seem to have been proprietors of the lands of that name for several hundred years. In 1628 a John Gray succeeded his brother, and in 1678 acquired three quarters of the lands of Dalmarnock. He was a Covenanter, and the persecuted ministers in the “killing times” found in him a protector. He was the first to work the Carntyne coal. He lived to a great age. His grandson vigorously prosecuted the mining industry at Westmuir Colliery, which was among the oldest in the West of Scotland. This grandson was a namesake of the old Covenanter, but he apparently did not cherish his ancestor’s sentiments, for he was a Jacobite, and showing some disposition to join the ranks of Prince Charlie in 1715, a sound-minded governess in the person of a worthy spouse, Elizabeth Hamilton of Newton, gave information of his intentions to the authorities, in-consequence of which he was thrown into prison. He died in 1742.

Robert Gray, who died in 1832, was Deputy-Lieutenant for Lanarkshire and an active magistrate. The son of this magistrate used to tell a story which shews that the Covenant and Presbyterianism seem to have run in the family blood, notwithstanding the errancy of one scion of the house. When the Episcopal Chapel near the Green—the first place of worship to have an organ after the Reformation—was in the course of being built, his aunt, who was a Mrs. Hamilton, happened to be taking a walk in the Green during the masons’ dinner hour. She saw their mallets lying about, and hiding one in her huge muff she marched away with it muttering, “If ilka ane would do as I am doing this day, the house of Baal would not be biggit for twelve months to come.” (1- Old Glasgow Essays. The prejudice against Episcopacy had not yet died down amongst the worthy Presbyterians of Glasgow, being almost as strong as their prejudice against the theatre) Robert Gray was succeeded by his only son, Rev. John Hamilton Gray, vicar of Derbyshire, dean of Chesterfield, and an accurate scholar and genealogist. At his death (1867) the male line of Grays became extinct.

The Bogles are in evidence in the district from very early times, and had farms on the bishop’s lands at Carmyle in the beginning of the sixteenth century.

“THE BOGLES”

“Then I straightway did espy, with my slantly, sloping eye

A carved stone, hard by, somewhat worn,

And I read in letters cold—Here lyes Launcelot ye bolde

Oft ye race off Bogile old Glasgow borne.”

They became proprietors at Shettleston, Daldowie, and Bogleshole, having previously been rentallers or tenants. George Bogle of Daldowie became connected, by marriage with a daughter of the house of Sinclair of Stevenston, with the Earls of Crawford. He was Lord Rector of Glasgow University in 1737, 1743, and 1747. The old portion of Daldowie House is said to have been built by him before 1745.

Daldowie was in the Bogle family just one hundred years, and after being held by John Dixon of Calder Iron Works, was sold in 1830 to James McCall, a respected merchant in Glasgow, whose descendants still hold the property.

Of the Bogles of Shettleston there were four Roberts, the third of whom married Jean Carlyle. Their second son Archibald was ancestor of Gilmorehill, and had a daughter Margaret, who married the novelist Michael Scott, author of “Tom Cringle’s Log.” The Robert Bogle of Shettleston who died in 1790 married a Miss Wood of Largo. The government at Edinburgh gave her ancestor—Sir Andrew Wood—the Largo estate for his services against the English at sea in his vessel the Yellow Garvel, against whom Sir Andrew was frequently victorious. The third son of this couple was postmaster in Glasgow, and died in 1806. Shettleston estate passed in 1762 to James McNair of Greenfield.

The Findlays of Easterhill or Easter Dalbeth acquired the property from Hopkirk of Dalbeth in 1784, who bought it from Archibald Smellie in 1783. Smellie obtained the estate in the middle of the eighteenth century, built the mansion-house, and resided in it for many years. Smellie was a merchant in Glasgow, one of the ” Kings of the Causeway,” and Dean of Guild, 1769. The Wardrops of Dalmarnock held Easterhill in the time of Queen Anne, which formed in ancient times part of the lands of Easter Dalbeth.

The first Findlay of Easterhill was Robert, merchant in Glasgow. He was the son of Dr. Robert Findlay, professor of Divinity in Glasgow University. He was Dean of Guild in 1797. His wife was a daughter of Robert Dunlop, fourth son of the second James Dunlop of Garnkirk. His son, also Robert, was an eminent merchant and banker. Dying in 1862, at the age of 78, he left the property to the late Mr. Findlay, whose widow resides in the neighbourhood of Lanark, at Bonnington House. Mrs. Findlay was a Buchanan of Greenfield, Shettleston.

The Buchanans of Mount Vernon have their origin from Drymen—”the Buchanan country.” They were the Buchanans of Gartacharan or Gartacharn. George Buchanan, merchant in Glasgow, acquired Mount Vernon about 1756, and built the older portion of the mansion, house, afterwards altered and improved.

The name of the estate is recent. The ancient name for Mount Vernon was Windyedge, which was altered by George Buchanan to Mount Vernon at the time of his purchase (circa 1756). The Buchanans were Virginian merchants. The Virginian tobacco plantation of the Buchanans was bounded by that of the elder brother of George Washington., which was called “Hunting-creek,” on the banks of the Potomac. Lawrence Washington had served under the fine old British Admiral Vernon, when he was on the American station. In mutual compliment to the British hero, Washington and Buchanan changed the names of Hunting-creek and Windyedge respectively into Mount Vernon. The estate is still in the hands of the Buchanan family. The late Col. Carrick Buchanan of Drumpellier was George Buchanan’s great-grandson.

The Hutchesons were associated with the district of Nether or Wester Carmyle, Thomas Hutcheson (1579) having come into possession of this portion of the Carmyle lands. Thomas was the father of George and Thomas Hutcheson, founders of Hutchesons’ Hospital and schools. The youngest of his three daughters was married to a Ninian Hill, who followed the brothers in the ownership, and is ancestor of Dr. Hill, of Messrs. Hill & Hoggan, and clerk of the Hutcheson Trust.

The Sligos of Carmyle have held the estate for a considerable period, but they do not properly belong to the old Glasgow families connected with the district. A hundred years ago John Sligo of Carmyle took an interest in the Tollcross Church, and was indeed the highest contributor to the original church building fund; and in later years representatives of the family sat in the church. The present representative, Mr. Smith Sligo, has his residence in the cast of Scotland, and is a member of the Roman Catholic communion.

CHAPTER III.

INTERESTING PERSONALITIES CONNECTED WITH THE VILLAGE AND NEIGHBOURHOOD

In the burial-ground of the church, underneath a memorial stone placed in the north wall of the cemetery, lie the remains of William Millar, the poet of childhood, author of the well-known “Wee Willie Winkie.” Millar was born in the Bridgegate of Glasgow in 1810, and spent his early years in the village of Parkhead. Disappointed when a lad of sixteen, through severe illness, of entering the university as a medical student, he was apprenticed to a wood turner, in which craft he attained to great proficiency. His poetic reputation chiefly rests on three pieces—” Wee Willie Winkie,” “John Frost,” and the “Sleepy Bairn.” The first was described by the late George Gilfillan as “the greatest nursery song in the world,” in which he is sustained by Robert Buchanan. This eulogy of Millar’s effort was pronounced at a meeting in the City Hall, at the close of which Gilfillan was accosted by a tall old man who, with moistened eyes, said he was the author of the song. His collected works appeared in 1863, and in 1902 a new edition was published. A monument was erected to his memory in Glasgow Necropolis, which has led to the general supposition that he was buried there; but this is an error, the fact being as has been stated above. He died at Glasgow on 20th August, 1872.

David Wingate was a poet of genius, who, in the leisure hours snatched from a busy life, devoted himself to literary composition of various degrees of excellence. For several years he resided in Tollcross, where his family still remain. He died at Mount Cottage in the village on 7th February, 1892, and was buried in the churchyard of Dalziel. Mr. Eyre-Todd in his “Glasgow Poets,” says that Mr. Wingate was born at Cowglen, near Pollokshaws, in January, 1828. He had very early to go to the pit, having lost his father when he was five years old, and was practically self educated. A lover of nature, he delighted in long rambles into the country, when he generally carried with him a plaid with which to cover himself, should need arise to spend the night in the open. Wild flowers were his hobby. He wrote stories, poems and songs, which appeared in the Glasgow Weekly Herald, Glasgow Citizen, Good Words, and in Blackwood. His first volume, published in 1862, established his title to the name of poet, and was highly praised by Lord Neaves in a review which appeared in Blackwood’s Magazine. His reputation expanding, he became acquainted with men of letters, which gave him the means of attending the Glasgow School of Mines, by which he qualified himself for the position of colliery manager, which he filled successively at various places, and finally at Toll-cross. Several volumes issued from his pen, and in 1883 Mr. Wingate in recognition of his literary work received a civil pension of £50. He was twice married, the mother of his children being his first wife. His second wife, Margaret Thomson, was a descendant of Robert Burns.

John Breckinridge was a poet and good-humoured songster to his native place; to the outer world, a famous maker of fiddles. He wrote some fine poetry, amongst other pieces ” The Humours of Gleska’ Fair,” but he never could be induced to publish them. The only poem that became generally known was the one just mentioned, which was published against his will. This was done by a singer called Livingstone, who made the song exceedingly popular, and the author never forgave him for his action. Old Gibbie Watson, the Parkhead baker, was a cronie of the poet, and when Watson was on the eve of starting his bakery, a number of friends assembled in the “Black Bull” to give him an auspicious send off. Gibbie stood the pies, and the others the porter. Breckinridge was called upon to open the concert, which he did in the following verses :—

It’s auld Ne’er-day nicht, an’ we’re met i’ the ” Bull,”

Wi’ our hearts dancin’ licht, an’ a bowl flowing full,

Let envy and spite throw aff a’ disguise,

And drink to young Gibbie that’s gi’en us the pies.

Noo, here’s to us a’—man, wife, lad and lass—

In peace and good humour this nicht let us pass,

An’ when on the morrow we think on the fray,

May conscience against us hae nothing to say.

Breckinridge was born at Parkhead in 1790, and, like almost every other man in the village, was a handloom weaver. In his early manhood he joined the Lanarkshire Militia, and served a term of five years in Ireland. He was a small, rotund, dark-eyed, blithe man, a lover of fun, and would dress as a foreigner and pass through the village playing his fiddle without recognition. One of his dying acts was to cause to be cast to the flames the monuments of his genius and humour—poems, songs and epigrams. He died towards the close of 1840, and was buried in Tollcross Church-yard.

James Beaumont Neilson was a native of Shettleston, where he spent the early years of his life as a working mechanic. One of the chief causes of the rise of the district was not only the abundance of black-band ironstone, but the substitution of heated for cold air in keeping up the blast. Neilson became manager of the Glasgow Gasworks, and while holding this position he discovered the advantage of applying air at a high temperature to smelting furnaces. The patent was tried with complete success, first in Clyde Ironworks, and immediately adopted at William Dixon’s Calder Ironworks; and from that time onwards dates a vast development in smelting operations. “In 1829 Clyde Ironworks were using eight tons one hundredweight made in coke for the manufacture of one ton of iron. Two years later they were enabled by means of the hot blast to double their output and use two tons five hundredweight of coal in its raw state per ton of iron.” Neilson was born in 1793, and died at Queen’s Hill, Glasgow, 1865.

James Martin, town councillor for a lengthened period, and bailie of the City of Glasgow, and also for a time a manager in the Main Street Church, built a house in the outskirts of the village, in which he lived for many years. Bailie Martin kept the Town Council lively. Like Bailie Moir before him, he amused, provoked, or instructed that august assemblage. His wife was connected with distinguished families of the Church of the Relief. They both lie in Tollcross churchyard.

George Honeyman was the biggest man in the village of Parkhead, and perhaps in the city, his weight being enormous. He was the keeper of a flesher’s shop and of a tavern. He came to Tollcross Church regularly, but he never sat down, preserving a standing position throughout the lengthened services, which were a feature of the worship of those old times. The size of Mr. Honeyman, together with the posture, made him a very prominent figure in the congregation of his day, and he never could be forgotten by any who in his time frequented the church. The only other man who could put in any claim to approach Mr. Honeyman in size, although this was but at a distance, was the father of Mr. John Cherrie, late of Clyde.

CHAPTER IV

SOCIAL CONDITION OF DISTRICT TOWARDS THE CLOSE OF THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY

The close, as contrasted with the commencement, of the century marks a striking change for the better. The poverty-stricken appearance of the people no longer obtruded itself. The cultivation of the soil was conducted on more scientific principles with more satisfactory results. Farms had risen greatly in value. A farmer at the beginning of the nineteenth century would have jumped at the offer of land at two and sixpence an acre which, a hundred years earlier, a competent authority declares would have been rack-rented- at half that sum. (1- Graham’s Social Life of Scotland, 18th century) It could no longer be said that the lairds might “have a pickle land, a mickle debt, a doocot and a lawsuit, but never a full purse.” It was not difficult to find capital to improve the soil, and skill to drain it. A century before he might be deemed lucky who could find change for a £10 note within half a dozen county towns ; now he could get it in any country village.

Rye-grass and clover—formerly despised as “English weeds”—potatoes and turnips were conspicuous on every countryside. Better farming yielded heavier crops; heavier crops yielded larger profits. To assist the growing prosperity, the roads, in contrast with their state at the beginning of the century, were no longer mere tracks, fit only for cadgers with their creels, but highways in the proper sense. When the tumbril, holding somewhere about as much as a big wheel-barrow, carried (1723) a load of coal to Cambuslang from East Kilbride, it was a miracle to see, and crowds came out to have a look at the wonderful machine. In 1800 carts and wheeled carriages were familiar objects. With greatly increased means of communication there came a greatly increased commerce, and the farmer was able to get much more easily to market. The produce of the field, the produce of the factory, the produce of the mine could be taken into town “at a tenth of the former cost in a tenth of the former time.” And as a result better buildings housed a people more accustomed to greater comforts; better food appeared on the table, and better clothing covered their backs.

The increase of wealth and of demand for labour brought about increase of wages and enhancement of prices. The average wage (1750) for the best ploughman was equal to £7 a year. The weaver or mason had sixpence a day, the collier about tenpence. Ten years before the church was built the wage of the ploughman was about £15 a year, the weaver or mason had one and twopence, and the miner two and sixpence or two and tenpence a day. Sheep sold at the beginning of the century at two and sixpence each; at the close they fetched from nine to eighteen shillings. Ayrshire cattle at the end of the century yielded “twelve pints (Scots) of milk a day, as compared with two, and at the highest three, at the beginning.” Horses cost about from £3 to £7 in 1700; in 1800 they were worth from £15 to £20.

There was also a revolution in the style and efficiency of agricultural instruments and general farm requisites. There were better ploughs, better harrows, better saddles and harness; and in particular the stupid old Scottish prejudice against the introduction of novelties—so marked in isolated communities—had sensibly declined. No farmer at the beginning of the nineteenth century, however pious, would have dreamed of rejecting an improvement on grounds such as his ancestors of a century earlier rejected the use of Meikle’s fanner, described by Mause Headrigg as “that new-fangled machine for dichting the corn “—to wit, it was an uncanny thing which “raised the devil’s wind.”

Manufactures kept pace with agriculture, and even outran it. In 1782 Menteith made muslin in Glasgow. Muslin weavers crowded Parkhead, Tollcross, and the neighbourhood; the noise of the clatter of the shuttle was heard throughout the villages; all found employment, there being plenty to do and plenty to win.

In ilka house, frae man to boy,

A’ hands in Glasgow find employ;

E’en little maids, wi’ meikle joy,

Flow’r lawn and gauze.

Or clip, wi’ care, the silken soy

For ladies’ braws

Their fathers weave, their mothers spin,

The muslin cloak sae fine and thin,

That, frai the ankle to the chin

It aft discloses

The beauteous symmetry within—

Limbs, neck and bosies ! “(1- John May, 1759-1836)

Cotton bleachfields were set up in the city (1785), and not long afterwards appeared the bleachfield at Carmyle. The Forth and Clyde Canal was completed (1790) ; the Clyde began to be altered into a deep waterway admitting vessels of size ; Henry Bell’s Comet commenced (1812) to ply on the river ; and Tennant founded (1801) the chemical industry, ” the highest chimney in the world marking the site.”

The causes which in general gave so strong an impetus to trade and agriculture did the same for the coal industry. Pits were fitted with modern gearing, and shafts to new mines were sunk. The steam engine now aided the coalmasters’ enterprise. The mines of Carntyne had long supplied fuel to Glasgow. In 1768 the first steam machinery erected in the West of Scotland for drawing off mine water was erected in Carntyne, taking the place of the ponderous and insufficient windmill previously in use, and blown to fragments in the wild storm of the ” windy Saturday.”

There is a tradition that an old thorn tree once grew on one of the Carntyne farms under which a large copper pot had stood when the plague was fierce in the city. In this pot the money from the town to purchase coal was boiled for purposes of disinfection. The hillmen at the pit received the money in long-shafted iron spoons, by the instrumentality of which it was thrown into the pot.

An early factor in the prosperity of Glasgow and our district was the rise of the “tobacco lords,” many of whom became lairds in the neighbourhood, such as the Buchanans, Bogles and Dunlops. They imported cargoes of tobacco and rum from the colonies of Virginia and Maryland. For a time nearly the whole of the tobacco trade of the country, and a wide portion of the Continent, was in their hands. They grew excessively rich, became magnates of the city, set up banks, led society, gave themselves airs and assumed superiorities. Strutting on the “plain stanes” of the Trongate as “Kings of the Causeway,” no humble tradesman dared set his foot on the same pavement. It was a fine and gallant show they offered as they marched up and down the causeway with high heads, clad in their “cocked hats, knee breeches, powdered wigs and scarlet cloaks.” Their collapse came with the first American War; but the city suffered only temporarily, and by the close of the century it and the districts surrounding had resumed their march towards a larger and more widespread wealth than ever.

When the village began to grow, the manners of the people had become less coarse, and the tyranny of ecclesiastical rule less stern. The “seizers” or “compurgators”—namely, the elders and deacons—who traversed the town or village streets, peering in at the doors and windows to arrest idlers and desecrators of the Sabbath, had ceased out of the land. The kirk session records no longer contain such charges as ” throwing clods on the people in time of worship; ” neither is there necessity any more to ” cause make a lash with a long handle, considering that herds and boys make disturbance during divine service in the loft.” The severe discipline of an earlier and more uncivilised age would no longer be tolerated, which compelled offenders to stand at the church door clad in sackcloth, bare legged in a tub of water during the ringing of the bell. The myriad-headed sermon was curtailed, and the theology softened.

The ministry shared in the benefits of an increasing prosperity. Principal Lang of Aberdeen instances cases in the end of the seventeenth century, in which the “minister of Campsie—’ ane auld man ‘—rejoiced in a stipend worth about £9. The minister of Lowrie was poorer by £2, and the minister of Cadder, for want of a house, lived in the church steeple.”(1- It must be remembered that the ministers of those days were practically also farmers) The case of the teacher was even harder than the minister; but in the period under notice, while minister and teachers’ support was far from being generous, it was a great advance upon that of the earlier time.

Unfortunately, amidst all the changes for the better, which are manifest at the close of the eighteenth century, education had not proportionately advanced, nor indeed for long afterwards; and the writer has a lively recol¬lection of the straits to which he was driven when marrying couples, by the inability of bridegroom and bride, or their witnesses—sometimes of all together— to subscribe their names in the marriage schedule. As for the drinking habit, it increased instead of diminishing as the eighteenth century advanced.

CHAPTER V

THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE VILLAGE AND DISTRICT

The origin of the village dates from after the middle of the eighteenth century. In a statement by a witness for the defender in the well-known Harvey-Dyke case (1823), before the Court of Session, it is affirmed that “the villages of Bridgeton, Parkhead and Tollcross have all been built within the memory of men” still living.

The village owes its existence to the general developments sketched in the former chapter—to progress in methods of agriculture, to new inventions, such as those of Arkwright, James Watt and Stevenson, to the establishment of crafts and manufactures, especially handloom muslin weaving and cotton bleaching, to coal mining, [and to the construction of the Clyde Ironworks.

The original Tollcross seems to have been made up of a house or two situated in ” High Dennistoun,” a house or two standing in ” Low Dennistoun,” (1- Low Dennistoun marked the site of that building which Mr. Shaw, flesher, occupies as a shop) and a small hamlet at the west end which has been partly removed, although some of the old relics with their outside stairs are still in evidence. In Easterhill Street, on the lands of Auchensuggle, there is also a trace of old Tollcross, in the house once occupied by the late Miss Reston. As the village had its origin subsequent to the middle of the eighteenth century, the original houses, far removed as they are from our modern ideas of convenience and comfort, are not to be confused with the houses of the preceding generation in the landward districts of the country. Humble and incommodious as they were, they marked a very distinct advance on the hovels which had preceded them all over the country.

The district immediately before the development of the village was agricultural and sparsely populated. Not more than twenty houses, it is said, could be “seen for a mile around it. In the eastern or Old Monkland portion a considerable breadth of flax was sown, which the women spun in the evenings, and which when woven into linen they stored away for future use. Every thrifty and well-to-do housewife was the possessor of finely bleached linen which filled all her depositories. The flax raised in the neighbourhood was for a time highly remunerative to all concerned. It was ready for pulling about the beginning of August. Nine women at tenpence a day could harvest an acre of it, and according to the Statistical Account profits so large that they seem to be an exaggeration could be made (1750) from its cultivation. As the cotton and muslin industries developed, the flax growing and linen industries gradually declined.

A writer, quoted in the New Statistical Account, describes the eastern or Old Monkland portion of the district as having the ” appearance of an immense ‘ garden,” and no doubt the landscape was then, as it is still, very beautiful, notwithstanding tin’ disfiguring changes which industrial enterprise has made in Its appearance. At the head of Carmyle Avenue, and around that neighbourhood grew a considerable quantity of wood.

Until recent years the prosperity of the village was largely identified with the Clyde Ironworks and the pits connected with them. The first iron furnace to be erected in Scotland was built—strangely enough—on Loch Etive in the West Highlands (1754), but the ironstone came by sea from England, and the smelted iron returned to England. The first real ironworks in Scotland were those of Carron, begun by Messrs. Roebuck, Caddel & Company in 1760. The works of Carron were the best of their day. The whole product of their furnaces was used up in articles of their own manufacture. From those furnaces came the pieces of ordnance known as “carronades” and other guns, down to such articles as grates, stoves, pots and pans. The battery train guns of the Duke of Wellington all came from Carron. Roebuck of the Carron Company was associated with James Watt in his steam engine patent.

The Clyde Ironworks were an extension of those of Carron, and were erected about 1780 to relieve the pressure there. The same kind of manufacture which distinguished Carron was, at least for a time, produced at Clyde, and relics of the old ordnance may to this day be seen by any visitor to the ironworks. The extension from Carron began originally as a foundry, employing about one hundred men. It was built on the lands of Bogleshole, on ground which anciently had been a burying place. When digging for foundations various urns were discovered containing ashes mixed with human bones, on some of which were the traces of fire.(1- New Sta. Ac. of the Monklands) Four furnaces were in blast as early as 1786.

The Clyde Works remained in the hands of the Caddels of Carron till 1810, and the same family, a branch of which is resident in the neighbourhood of Bowness, are still associated with the Carron works. Colin Dunlop, afterwards M.P., was working the coals in the district of Carmyle. In that year he bought the ironworks from Mr. Caddel. Mr. Dunlop, ever alive to new ideas, had Neilson’s patent tried, as already observed, some eighteen years later with complete success—a patent not altogether new in principle, but by Neilson first applied to the fusion of iron.

The blaze from the furnaces, especially when in full operation, illuminated the district for miles around; and when ultimately the progress of science showed the way to new and more economical and profitable methods which necessitated the darkening of it down, the want of it gave a dismal character to the night never before experienced by the natives, and especially to those of them whom it used to light home when

Owre late out at e’en.

It was in happy allusion to the illumination shed abroad over the country-side by these furnaces that the Bridgeton poet, Alexander Rodger, wrote—

The moon does fu’ well when the moon’s in the lift;

But oh! the loose limmer tak’s mony a shift:

Whiles here, and whiles there, and whiles under a hap—

But yours is the steady licht, Colin D’lap.

Na, man! like true friendship, the mirker the nicht,

The mair you let out your vast columns o’ licht,

When sackcloth and sadness the heavens enwrap,

‘Tis then you’re maist kind to us, Colin D’lap.

The mansion-house of the Dunlop family, although Mr. Colin lived at Clyde, was, up to 1852, the old mansion-house of the Corbets. In this house the great speculator, James Dunlop, father of the Member of Parliament, died in 1816. It is described as “a good and substantious house, with gardens and enclosures.” The drawing room opened on a trim bowling green. On a stone bench in the open porch sat in old times the familiar “gaberlunzies,” or privileged beggars, waiting for the laird or the “leddy.” The grounds in which the mansion-house stands appear to have been from ancient times in the possession of the proprietors of Tollcross, and nothing the writer can find encourages the theory that the bishops of Glasgow had at any time a palace in the park. Many of the Corbets lived and died in the ancient mansion-house. The town house, castle, or palace of the bishops adjoined the cathedral; and from the beginning of the fourteenth century until the Reformation their manor-house was Lochwood—the “castle of the lake “—six miles north and east of the city, in the vicinity of their ancient forest, near the shores of the Bishop’s Loch, and then within the Barony.

Bishop John Cameron died on Christmas Eve, 1447, at Lochwood. He did not bear a good character in the countryside, nor in the country generally, and was reputed to be of the sort whom maternal superstition might readily turn into a black bogle with which to frighten fractious children. Poor Cameron has very likely been served worse than he deserved. Buchanan the historian paints him with a very black brush, retailing the legend that while asleep in his country house at Lochwood, he seemed to hear “a loud voice summoning him to appear before the tribunal of Christ. Suddenly awakening in great perturbation, he roused his servants and ordered them to sit by him with lighted candles; and having taken a book in his hand began to read, when a repetition of the same voice struck all present with profound horror.” When, for the third time it sounded louder and more terrible, the bishop gave a deep groan and was dead, “his tongue hanging out of his mouth.” This Buchanan calls “a remarkable example of divine vengeance for many acts of cruelty and rapine.”

The district is not particularly rich in historic incident. The Covenanters, retreating (1679) from their unsuccessful attempt on Glasgow, drew up on “Tollcross Muir, about a mile or two from the city.” There is also a tradition that Prince Charlie encamped on the rising ground above the farm of Hollowglen in Shettleston in the ’45.

Some thirty years afterwards (1774) the church of Shettleston was erected as a chapel of ease, Shettleston at this time being included in the parish of Barony. It had a population of about seven hundred and sixty-six. The old manse which was ultimately burned, but not before part of it had been degraded to the uses of a stable, stood on the road to the ” Wellhouse; ” a figure of Christ is believed to have been carved on its walls. Besides the chapel of ease there was formerly a Reformed Presbyterian Church. After the Disruption a Free Church was erected in Eastmuir, the pastor of which was Mr. Stewart, the minister of the chapel of ease being Mr. Thomson. Stewart’s parents kept the old tavern of “The Ram,” but his wife served at the bar, her husband being bedridden. During the ministry of Mr. Reid the congregation removed to Sandyhills, where it still worships.

Before 1828 the well-known Dr. Black, ultimately colleague to Dr. Burns of the Barony, was minister of the chapel of ease. Dr. Black was born in the neighbouring parish of Cadder, and descended from a good old yeomanry stock. Principal Marshall Lang, formerly of the Barony, tells a story to the effect that people used to say to Black when colleague to Burns, “Mr. Black, you’ll be wearying for Dr. Burns’ death.” To which he would reply, “Not at all; I am only wearying for his living.” The Roman Catholic Chapel was built in 1857.

The colliery of James McNair claims to be the first on which was erected in the West of Scotland a steam engine for drawing off water, the date being given as 1764. Another authority states that the earliest steam engine for this purpose was put together on the Carntyne-Colliery of Mr. Gray in 1768. It has been affirmed that about the same time there existed a colliery at Mount Vernon said to be sixty fathoms deep; but this is very unlikely.

At the beginning of the nineteenth century a single dwelling house which still stands, marked the Sheddens of Shettleston. The houses were thatched, low and earthen-floored, and many were beneath the level of the street; they had long strips of garden behind. Houses stood also in Eastmuir, which in the days of the Edinburgh coaches had an evil reputation for bad smells; but ultimately it got its character cleared by an official report of the authorities of Glasgow in which it was declared to be as sanitary a village street as that of any suburb of the city. Water was introduced into Shettleston in 1869, the population then being about 2,500. The pits before this had supplied the water to the inhabitants, who carried it away by means of the once familiar “stoups”—things unknown to the present generation.

Some few years after the Church of Tollcross was built, wages had made a considerably forward stride. Miners were paid from two and ninepence to three shillings a day; weavers had ten to fourteen shillings a week, and some experts had even twenty shillings; labourers at the harvest had from one and fourpence to one and sixpence, and women one shilling a day; domestic servants received from £6 to £10 a year.

Valiant attempts at education seem to have been made in Shettleston. A school was taught by a person of the name of Kingham, whose successor was Andrew Garrand, registrar and session-clerk. One shilling a quarter was charged as school fee. Another day school is said to have stood opposite the parish church.

The “Tollcross Muir, about a mile from Glasgow,” supports the inference already noted that the lands of Tollcross were formerly more extensive than in the present time. As a matter of fact Janefield, or Jeanfield, which is more correct, was part of the Tollcross estate. Now a cemetery, it was first occupied as a farm and then as a nursery, James Corbet (1751) having feued it to a William Boacher of Edinburgh, nurseryman, a daughter of whom became the wife of the celebrated Robert Foulis, printer in Glasgow to the University.

Jeanfield, in extent about twenty acres, was afterwards purchased for £81 by a Mr. Patrick Todd, merchant in Edinburgh. But shortly afterwards (1758) it fell into the hands of the shrewd and eccentric Robert McNair, whose peculiarities have immortalised him in Glasgow annals. McNair bought Jeanfield for £100, and built thereon a mansion (1764), which was a burlesque of architecture, and the laughing stock of every passenger entering Glasgow by the Edinburgh and London coaches. The story of McNair’s purchase is to the effect that, having been asked for a bond for the price, he pulled from his pocket a greasy leather bag, and pouring out its golden contents upon the table, exclaimed, “Na, na! Nane o’ yer gauds for me! Here’s Jean’s pouch; gi’e me the papers! “(Jean was his wife.) Hence the origin of the name. “The little hill of Tollcross, by this transaction, became the field of his wife Jean, or Jeanfield.”

Although not strictly pertinent to the purpose of this sketch, we may be pardoned if we pursue McNair a little further. The name of Jeanfield may be no improvement upon that of the Little Hill of Tollcross, but we are indebted to this amusing personage for an important change in the legal customs of the country, about the value of which there can be no doubt whatever. In those days it was a discreditable custom of the Crown, when successful in Exchequer trials, to pay each juryman a guinea, and treat him to a supper.

McNair getting somehow entangled with the Excise, an action was raised against him in Edinburgh. The Lord Advocate, addressing the jury, concluded by reminding them that in the event of bringing in a verdict for the Crown, they would have the usual fee and the usual feast. McNair, turning to the jury, replied with the ready permission of the judge, “Gentlemen, you have heard what the learned Advocate for the Crown has said. Now, here am I, Robert McNair, merchant in Glasgow, standing before you, and I promise you two guineas each and your dinner to boot, with as much wine as you can drink, if you bring in a verdict in my favour.” He gained his case. The Crown never made another attempt after this fashion to bribe a jury. Jeanfield was finally sold in 1846 to the East Cemetery Joint Stock Company, of which Mr. James Dunlop was a director.

The village was thrown into no small excitement by the passage through it (1788) of the first direct mail coach from London on the 7th July. The end of the journey was the Saracen’s Head Inn in Gallowgate, at the time the fashionable inn of the city. On that day the landlord, accompanied by a crowd of horsemen, rode out as far as Tollcross to meet it. The expected coach in due course appeared, gay with its red-coated driver and guard in scarlet livery, armed with cutlass and blunderbuss; for the roads, particularly to the south of the Border and in the neighbourhood of the towns, were with some reason deemed far from safe for the unarmed traveller. This coach ran at the rate of eleven miles an hour—an excellent speed that has seldom been surpassed then or since.

But there appears to have been coaching between Glasgow and London earlier than 1788. An advertisement in the Glasgow Mercury of 31st May, 1781, conveys the announcement that the diligence would set out “as usual,” from the Saracen’s Head, going by Moffat and joining at Carlisle the London diligence. This was a. three-seated chaise drawn by two horses, and the fare to Carlisle was twenty-five shillings. The proprietors engaged to take passengers to London in four days. This earlier service seems, however, to have involved a change of coaches at Carlisle, whereas the later offered the convenience of taking passengers onward without change.

McUre states that the magistrates of Glasgow (1678) entered into a contract with William Hume, coach proprietor, for the establishment of “ane sufficient strong coach to run between Edinburgh and Glasgow, to be drawn by sax able horses, to leave Edinburgh ilk Monday morning and return again (God willing) ilk Saturday night.” The fare was eight shillings in summer and nine shillings in winter, each passenger to have the liberty of taking a bag, to receive clothes, linens, and “sic like.” In 1749 the diligence ran twice a week, fare nine shillings and sixpence, with a stone of luggage, and performed the journey of forty-two miles in twelve hours. Thirty years afterwards (1779) John Gardner started from the Buck’s Head Inn, Glasgow, a four horse coach to Edinburgh which did the journey in six hours, reduced still further in 1840 to four and a half.

Travelling at that period was both expensive and adventurous. The poor could not travel by coach at all, and when the rich left home it was with more concern than they now prepare to visit the ends of the earth. They arranged their affairs, in many cases made their wills, and took along with them male servants armed.

Scotland was too poor a country for the ambitious and swell highwayman, but the roads were by no means secure from lower and more brutal depredators; and the outskirts of our peaceable and law-abiding village were not entirely immune from their unwelcome pranks. At the northern end of Carmyle Avenue the road at this period passed through a small wood. The practicability of robbing the coach occurred to some bold thieves, and it was judged that this spot might be a favourable one for the execution of their enterprise. The coach was expected to pass the head of the avenue early on a winter morning, and the brilliant idea suggested itself that a strong rope tied to one tree and carried across the road to another on the opposite side, at a height sufficient to entangle the coachman and guard, would throw them from their respective seats owing to the rapid motion of the vehicle, when in the confusion they would have their chance. Unfortunately for the success of their designs, it happened that a waggon of hay was accidentally on its way that morning to the city, which, being stopped by the rope, the contemplated robbery was frustrated. There are traditions of various robberies of the mail coaches connected with the district. There is the story of an old woman who was said to be murdered at the head of Carmyle Avenue, in a house at the “Flush “which is still standing. The perpetrator of the crime is said to have been nearly caught, but his pursuer tripped just at the moment he was in the act of laying hands upon the murderer, who got away leaving no trace until this day.

Another tragedy is believed to have happened at the southern end of the avenue. Two mutual friends, according to the tradition, fell in love with the same fair maiden. Friendship, as is common in such circumstances, turned to jealousy, and jealousy to hatred. The friends quarrelled, fell to angry words, and in hot excitement drew swords against each other—they all carried swords in those days—when one of them sank to the ground mortally wounded. The other, horrified at what he had done, destroyed himself. They were buried in the same grave, digged at the place where they died; and it has ever since been known as the “Bluidy Neuk.” According to an old lady of Carmyle, the place is “no canny.” It is said to lie between Carmyle mansion-house and the little row of cottages at the opposite side of the field beyond.

A cause celebre which, some two or three generations ago set the whole of East Glasgow by the ears, was the law plea known as the “Harvey-Dyke” case. Thomas Harvey, or “lang Tam Harvey,” as he was commonly called, began the world as a carter at Port-Dundas. Thinking not without cause that a “change-house” would serve his ambition, which was of the “o’er-vaulting” order, much more readily than the loading of waggons and driving of teams, he gave up the carting and took to whisky selling. Soon Harvey’s change-houses or “divans,” as they were called appeared all over the city and became celebrated as first-rate in style and order. He quickly grew rich and bought Port-Dundas distillery for £20,000.

The ambition of Harvey expanded with his fortune, which was only in keeping, as he imagined, with his personal appearance, he being large and muscular, with short hair and red whiskers. He bought Westhorn in 1821, and furnished the mansion-house at a cost of £10,000, although he was a bachelor. He died poorer than when he began life, and is said to have ended as an actual pauper.

A public footpath ran along the northern bank of Clyde from the city to Carmyle—a distance of about five miles. Harvey to preserve the amenity of his property erected (1822) a thick stone wall on the west across this public footpath, which he carried down into the river and armed all along its extent with stout iron pikes. This wall the people demolished as an interference with their ancient and undoubted rights and liberties. Harvey rebuilt the wall, and the people again destroyed it.

On the second occasion (21st June, 1823) the destroyers were surprised about the time their work was finished by a detachment of dragoons. Some of the people were taken on the spot, some were arrested on the roads, forty-three in all, and a lad received a cut from a sabre in the arm. The throngs were tremendous. The whole of the highway between Tollcross and Camlachie was alive with people during the entire night—friends were anxious for their relatives, and the curious had itching ears.

James Duncan was a bookseller in Glasgow and also a landed proprietor. He organised the public opposition to the high-handedness of Harvey. Alexander Rodger, the Bridgeton poet, fanned the popular fury. Along with them a committee, amongst whom appear the names of George Rodger of Barrowfield Printworks, John Kinniburgh, feuar, Tollcross, James Reid, feuar, Parkhead, and Alexander Brechin, feuar, Carmyle, resolved to carry the matter to the Court of Session. Subscription sheets were heartily and extensively signed in Tollcross, Parkhead, Bridgeton, and elsewhere. James Bogle, writer in Glasgow, Colin Dunlop, member of the Faculty of Advocates, and Mr. McNair of Greenfield, gave evidence in favour of the contention of the people. The public were successful, but Harvey was not satisfied, and carried the case to the House of Lords, which finally (July, 1828) set the matter at rest by unanimously affirming the judgment of the Court of Session. As an example of the extraordinary interest and excitement which this famous law suit evoked in the district, it is recorded that when the witnesses on behalf of the community, many of whom were old men, were informed that the case had been gained, some of them burst into tears of joy, saying that they would have run any risk— it was a period when, owing to the extreme cold, travelling for aged people involved no little danger to health— in order to get back their favourite walk.

It has already been observed that the district was full of handloom weavers. They were a shrewd and respectable class, radicals in politics, led by “Colin D’lap,” and no inconsiderable theologians. Many of them might not be able to read, but they could lay down the principles of orthodoxy to the minister, and point the erring shepherd to the exact spot at which he had begun to lead astray the flock. In their cottages regular family prayers fed the fires of piety and virtue. The miners lived in fairly comfortable houses with a “but and ben;” went to and returned from their ill-vent dated pits, lifted an honest wage, and contracted the miner’s asthma, which brought them to old age at fifty years. Nevertheless, some of them lived to a very advanced period of life, proving not only the possession of strong constitutions, but strictness of habit and moderation in all things. They sat on their hunkers when their work was done, and gave in many a lengthened sederunt what contribution they could to the conversation and knowledge of their class.

Upon the ground they hunkered down a’ three,

And to their crack they yoked fast and free.

The old Scottish miner was, in general, a hard working and virtuous individual. He loved respectability as he loved his family, his dram, and his fishing rod. The off-day found him by the banks of the river searching for, and maybe finding a fine salmon, or in lieu of that dainty dish, the beautiful small par or fry of the salmon, thus rivalling the Rutherglen weavers, who “scourged the Dalmarnock Ford at a great rate.” It may be here said of this ancient river crossing, that pearls, not it must be admitted of a highly superior order, have been found taken from brown mussels embedded in the river, which the boys called cluggie-dhus or clubbie-dhus.(1- McUre’s Glasgow Facies, II., p. 815: Glasgow Past and Present, p. 282 )

Strange to say, a species of slavery existed amongst the colliers down almost to our own times. The collier became the property of the owner of the colliery when he entered the owner’s employment, and was bound to particular servitude in that particular work. The master could not sell the miner off the land to another, but if the owner alienated the ground on which his colliery stood, the collier passed over to the new owner.

Moss Nook was an old man, alive in 1820. Originally belonging to the estate of McNair of Greenfield, he was in that year in the service of Dunlop of Clyde, to whom he had been transferred many years before by McNair in exchange for a pony. But as the law then stood this was an illegal transaction. (1- Domestic Annals of Scot., III., 250)

At the beginning of the nineteenth century, while, public manners had become more refined as compared with those of a generation or two earlier, there still remained room for improvement. Among all classes cock fighting was a favourite pastime. Cockfighters had (1807) a temporary building in Queen Street, from which they were expelled by the authorities, and a spacious one (1835) in Hope Street. It is said that George Anderson, M.P., used to indulge in the sport, setting the birds to mortal combat on the flat of the top of his mill in Garngad Road. Around the village the cockfighter was in evidence. In earlier times boys were taught a love for the degrading sport in the very school itself. Every little fellow who could afford to bring to the school at certain times a fighting cock, was encouraged to produce it, when two of the birds were pitted against each other in presence of the gentry of the neighbourhood. The cocks slain in mutual fight became the property of the schoolmaster, who frequently had more benefit from the spoils of the cockfight than from the amount of the school fees.

When such was the character of the education received by the rising generation, it is not surprising that that rising generation’s children and grand-children should manifest some rather rough and brutal proclivities, or that session records should be disfigured with charges of brawling, outrageous conduct, or the use of violent and abusive language. The old minutes of Tollcross session are much the same as those of other kirk Sessions throughout the country. They are far from being pleasant reading. In truth, the piety of the end of the eighteenth and beginning of the nineteenth centuries was to a certain extent, of a morbid order—unction and evangelical sentiment not being always dissociated from a morality that was comparatively low toned.

The Dunlops fostered education, and a school was early in the village. The church in Tollcross also realised, to some degree, its responsibility, and gave its countenance and support, almost from its origin, to day schools and Sabbath schools. Yet, it is singular that while educational conditions were such that a church might well deem it a duty to assist schools and school teachers in every way, it threatened a half-starved teacher with legal proceedings for rent which he was unable to pay.

In Carmyle there are traces of attention to education in the latter half of the eighteenth century. James Bogle in evidence given before the Court of Session states that before going to the grammar school in Glasgow (1782) he was educated at the reading school in Carmyle, and traces of a schoolmaster in that village are found so early as the sixteenth century. An endowed school-house and teacher’s house were built in 1822 on a feu purchased by the trustees of William Lyon who, dying twenty years earlier, bequeathed a sum of money “for the education of poor children in the parish where he was born.” In Tollcross, Fullarton Hall and the church session-house were for many years utilised for educational purposes, and the teachers were in several cases excellent characters and very competent for their work.

In former times the colloquial expressions of the peasantry of the district, particularly in the Old Monk-land portion, where it was mainly agricultural, are exceedingly curious, and abound in grotesque phrases and epithets which to an outsider would be as unintelligible as an unknown tongue. Infidel was the word employed when it was designed to describe an idiot. To say, “Do you think I am an infidel?” was to say “Do you suppose I am a fool? ” “Will you never deval?” is “Will you never give over?” The man of questionable reputation was a “nomalistic” character. Filthy accumulations of animal or vegetable matter were “combustibles.” The different varieties of coal were distinguished as “yolk” or “cherrie,” “parrot,” “humph,” and “milk “coal. (1- Old Sta. Acc)

Home-brewed ale was the ordinary if not the sole drink of the peasantry up to 1750. It afterwards began to be partly supplanted by whisky, with bad results. In many districts drinking was described as “pewtering,” from the “two-penny” being served in pewter vessels. The practice which prevailed at the close of the Saturday pre-communion preachings, of the minister of the church to ascend the pulpit, and after giving out intimations, to give a lengthy resume of the Fast Day and of that day’s sermons, got the strange name of “Pirliecuing.”

Water was obtained in the village, as in Shettleston, from pits and wells. In 1806 the city was empowered to take it from the Clyde at Dalmarnock, which for many years thereafter supplied the wants of the citizens on the north side of the river, until the completion of the Loch Katrine scheme. The writer well remembers how, after a spate, the water taken from the Clyde was as brown and drumlie as pea soup.

CHAPTER VI

THE CHURCH OF TOLLCROSS

The church of the Relief originated in the deposition of the Rev. Thomas Gillespie of Carnock in 1752. He was a pious, conscientious, and altogether worthy man. It has been erroneously supposed that Gillespie was deposed on account of his uncompromising opposition to patronage, which was then working much havoc in the Church of Scotland. In reality patronage was but a branch of a wider question. The great principle for which the father of the Relief contended involved a denial of unlimited obedience to church courts when ministers were persuaded in conscience that church-court sentences were contrary to the word of God. The principle at stake was ecclesiastical and religious liberty.

The genius of the spirit of Gillespie has all along been characteristic of the church of the Relief. He was far in advance of the times in Scotland, and in no way in sympathy with the close principles of sectaries. “He desired that church courts should be consultative rather than legislative and authoritative.” This latitude of opinion became a marked feature, the church of the Relief having always been broad and liberal, and the authority of its synod “mild and lenient even to a fault.” (1- Struthers’ History of the Relief Church) At his first communion after deposition he declared, “I hold communion with all who hold the Head, and with them only.”

Gillespie stood for six years alone, but was supported by a letter of sympathy from President Edwards. He was then joined by the Rev. Thomas Boston of Jedburgh, whose father, author of the ” Fourfold State,” bore a name that was a household word among all the pious families of Scotland. The next congregation to go over to the cause of Gillespie was that of Colinsburgh in Fifeshire, the minister of which was Thomas Collier. Those three—Gillespie, Boston, and Colliers-formed the first presbytery “for relief of persons oppressed in their Christian privileges.” Several other congregations shortly followed, among them being Bellshill in 1763, the first Relief Church in the west; Albion Street in 1765, the first in Glasgow; followed by Anderston in 1770, and East Campbell Street, 1792. Greenhead was formed in 1805, and Tollcross a year later. The first Relief Synod met 1773.

From causes which have been indicated the village had grown, and the population of the district had increased, but no provision had been made for the religious wants of the augmented population. For three or four miles around the village, as well as for the village itself, there was but one church—the chapel of ease at Shettleston—which was overcrowded and totally inadequate. People who had inherited principles of spiritual and ecclesiastical independence; people who looked with disfavour on the high-handed action frequently at this time practised by the Moderate party in the Church of Scotland ; people who were already members of the Relief Church, and connected with churches in Glasgow, especially East Campbell Street, which had an elder’s district in Parkhead and another in Tollcross and Carmyle ; people who did not appreciate the ministry of the occupant of the pulpit in the chapel of case, formed a large proportion of the population.

The movement which issued in the formation of a new congregation at Tollcross originated, however, speaking in general terms, with those who were in the habit of attending the chapel of ease, and they were instantly followed by a large multitude.